The bigfin squid (Magnapinna) is one of the most elusive creatures that we know.

It dwells in the permanently dark depths of the ocean and is an extremely rare sight, with only around a dozen confirmed spottings worldwide.

Now, for the first time, bigfin squids have been seen off the coast of Australia not once, but five times - and each sighting was a different individual. It's not enough to call the region a Magnapinna hotspot, but the new observations have revealed new behaviours, underlining the importance of capturing images of deep-sea life in its natural habitat.

"These sightings, the first from Australian waters, have bolstered the hypothesis of a cosmopolitan distribution, and indicated a locally clustered distribution with squid being found in close spatial and temporal proximity of each other," the researchers wrote in their paper.

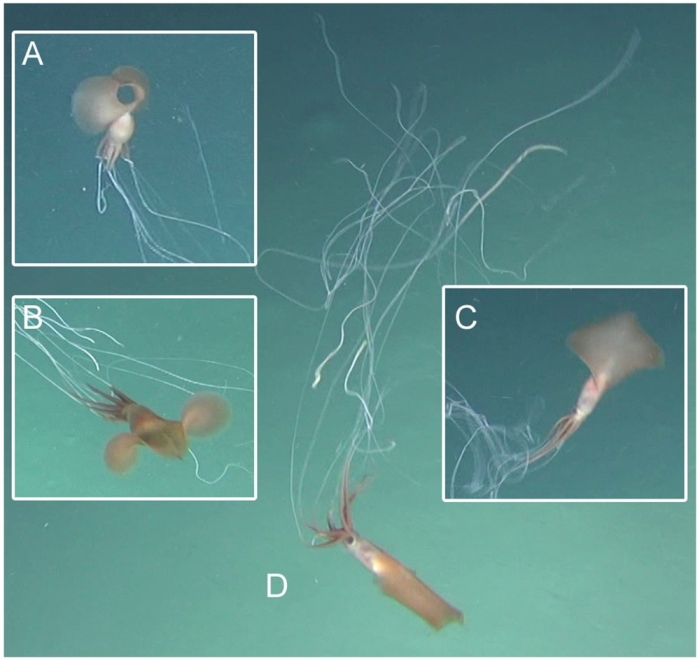

Bigfin squids are strange and eldritch beasties. Their bodies look fairly typical for a squid, although with much larger fins than is usual. But their arms and tentacles are truly peculiar, tipped with surprisingly long filaments, making the limbs reach lengths of over 8 metres (26 feet), many times longer than the squid's body. Held out at an angle perpendicular to the body, the limbs also give it a strange 'elbowed' appearance.

Because they live in the bathypelagic zone, between 1,000 and 4,000 metres (3,280 and 13,120 feet) deep, it's not easy for us to study these squids. At this ocean depth, sunlight never penetrates, and the pressure of the water is crushing.

However, remotely operated vehicles can go where humans fear to tread, and over the last couple of decades, sightings have gradually trickled in.

It was just such equipment that marine scientists were using to explore deep waters off the southern coast of Australia. In a region known as the Great Australian Bight, where almost nothing was known about the deep-sea fauna, scientists deployed remotely operated vehicles and a towed camera off the Marine National Facility's research vessel Investigator as part of an intensive research program to catalogue the life far beneath the waves.

On five separate occasions, bigfin squids showed up in the images obtained by the instruments.

The towed camera caught two squids, filming them for four seconds each at 2,110 and 2,178 metres, at one site in November 2015. The two sightings were around 12 hours apart.

The ROV spotted three squids at another site in March 2017 at 3,002, 3,056 and 3,060 metres below the surface. Because the ROV is more flexible, it was able to follow the squids, capturing longer video of each one; the longest was just under three minutes. All three sightings occurred within a 25-hour time period.

Morphological measurements with paired lasers suggested that each of the five squid sightings was a separate individual.

Magnapinna filmed at 3,056 metres. (Osterhage et al., PLOS One, 2020)

Magnapinna filmed at 3,056 metres. (Osterhage et al., PLOS One, 2020)

"These sightings represent the first records of Magnapinna squid in Australian waters, and they more than double the known records from the southern hemisphere," the researchers wrote in their paper.

Even so, the sightings were rare: the survey spanned over 350 kilometres of the Great Australian Bight, and recorded 75 hours' worth of video. The beasties were only seen at those two locations in those two timeframes.

"All Magnapinna sp. sightings in the Great Australian Bight were made in areas of predominantly soft sediment, in terrain of lower-slope erosion channels, and upper section of submarine canyon," the researchers wrote.

"Submarine canyons and similar incised features often support high productivity and diversity in the deep-sea, and these locations may reflect habitat preference of Magnapinna sp."

Although the sightings were short, they still yielded observations of some of the squids' behaviours. There was, of course, the characteristic 'elbow' pose with the tentacles extended outwards, then bent at an almost 90-degree angle. Previously, this had mostly been observed while the squid was vertical, but the new footage showed this pose in the horizontal position.

Because the tentacles appear to be quite sticky, this could be a feeding behaviour, waiting for some hapless creature to bump into the long limbs like a bug into flypaper, but we still don't have enough information to determine this for sure.

Another behaviour the team observed was the squid holding one arm perpendicular to its body while it moved from a horizontal into an upright position. This is similar to the dorsal arm curl movement seen in a number of squids, but why the bigfin squids do it is still a mystery.

In an entirely new behaviour, the researchers also saw one of the squids coiling its filaments close to its body. Previously, the only cephalopod seen doing something similar was the distantly related Vampyroteuthis infernalis, another bathypelagic creature that uses its filaments for feeding.

"Whilst there are obvious differences between the filamentous appendages of V. infernalis and Magnapinna squid .. it may be that coiling behaviour represents an efficient biomechanical solution to the retraction of such long, thin filaments," the researchers wrote.

It's fascinating, tantalising stuff - new information that highlights just how little we know about these strange, silent creatures and the deep, dark underwater world they inhabit.

The research has been published in PLOS One.