An international team of researchers has found what they're calling a "conspiracy" inside elliptical galaxies. It appears dark matter and stars are working together to alter the speed at which elliptical, as well as spiral, galaxies in our Universe spin.

This is the first study to map the motion of stars in large numbers of elliptical galaxies, and has shown that they move much faster than expected. This is the same thing that astronomers found was happening in spiral galaxies like our Milky Way 40 years ago - a result that first led to the discovery of a mysterious presence known as dark matter.

Since then, scientists have found that dark matter makes up about 85 percent of the mass in the known Universe, and influences the way that galaxies form, move and evolve. But we still understand very little about it.

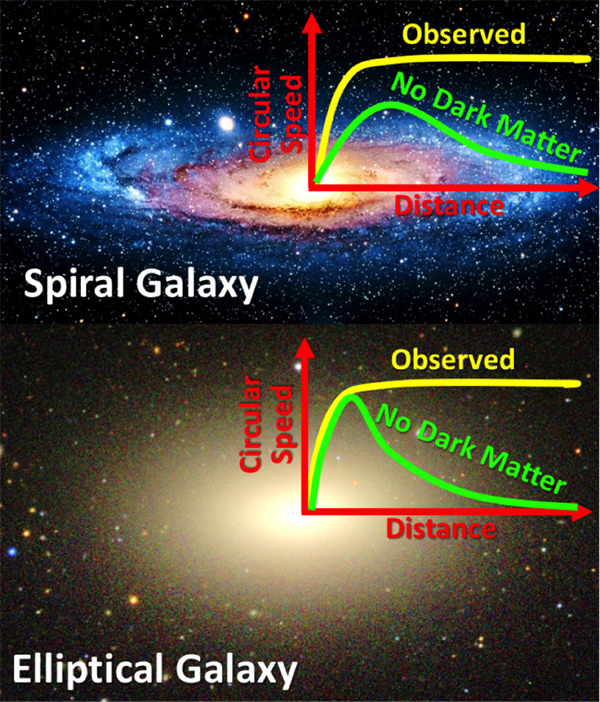

This new study, which involved astronomers from Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, is the first to suggest that dark matter is impacting elliptical galaxies in the same way it influences spiral galaxies. If it wasn't, the stars on the outside of the galaxy would move much slower than those at the inside, due to the waning effects of gravity.

"The surprising finding of our study was that elliptical galaxies maintain a remarkably constant circular speed out to large distances from their centres, in the same way that spiral galaxies are already known to do," the lead researcher, Michelle Cappellari, from the University of Oxford in the UK, told the press.

"This means that in these very different types of galaxies, stars and dark matter conspire to redistribute themselves to produce this effect, with stars dominating in the inner regions of the galaxies, and a gradual shift in the outer regions to dark matter dominance."

We know more about spiral galaxies than other galaxy types, which is understandable, seeing as we live in one, but spiral galaxies actually only make up less than half of the stellar mass in the Universe. The rest is dominated by elliptical and lenticular galaxies, which have puffier star configurations, and lack the trademark flat gas disks that spiral galaxies have. This puffiness has made the distribution of mass in elliptical galaxies hard to study up until now.

To accomplish this, the researchers from Swinburne worked with Cappellari's team to monitor elliptical galaxies using the world's largest optical telescope at the W M Keck Observatory in Hawaii. The team mapped out the speed of the stars in these galaxies, and then used Newton's law of gravity to translate these speed measurements into the amounts of matter distributed within the galaxies.

They found that the stars in the outer edges of elliptical galaxies behave surprisingly like those in spiral galaxies. The fact that this trend holds across two very differently shaped galaxies would mean that the dark matter "conspiracy" must be even more widespread than initially thought. Their results have been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

But not everyone is convinced, as the press release explains:

"The conspiracy does not come out naturally from models of dark matter, and some disturbing fine-tuning is required to explain the observations. For this reason, the conspiracy even led some authors to suggest that, rather than being due to dark matter, it may be due to Newton's law of gravity becoming progressively less accurate at large distances."

Either way, the new results provide important more insight into the 'dark sector' of the Universe, and could change our understanding of dark matter. And they just so happen to come at a time when we finally have the tools to begin to look for a dark matter particle, as Jean Brodie, one of the researchers, explained:

"This question is particularly timely in this period when physicists at CERN are about to restart the Large Hadron Collider to try to directly detect the same elusive dark matter particle, which makes galaxies rotate fast, if it really exists."

Love science? Find out more about the Universe-exploring research happening at Swinburne University of Technology.