A man and a woman who donated their bodies to science decades ago could never have imagined just what their physical generosity entailed.

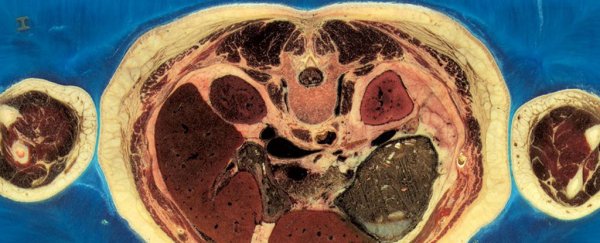

The image above is one of thousands from the Visible Human Project, a long-running scientific endeavour to create a comprehensive collection of cross-sectional imagery of the human body. The project began back in the 1980s and saw the most attention a decade later, when its first photographs were released to the public: a grisly scientific stockpile of thousands of cross-sections of two corpses.

Who were they? Little is known about the woman, other than that she died of heart disease at the age of 59 and lived in Maryland in the US. The man had a more chequered history: Joseph Paul Jernigan was a convicted murderer who was sentenced to death by lethal injection at the age of 39 in Texas in 1993.

Both cadavers were acquired by the Visible Human Project, and were imaged using both MRI and CT scans. They were then frozen and sliced up so their cross-sections could be photographed in painstaking detail. The man was cut at cross-sectional thicknesses of 1 mm, and the woman's slices were even thinner, with each slice being just a third of a millimetre thick.

Now a new team of researchers led by Sergey Makarov of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in the US has compiled new, high-resolution imagery of the woman's body to create a 'virtual human' for study and experimental purposes.

Their research, presented at the annual conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society in Italy last month, is the most detailed reconstruction of a human body ever, comprising a virtual 'phantom' body assembled from more than 5,000 digital images and overseen by a team of medical specialists.

"They have 10 times as much information as you'd get from an MRI scan," Fernando Bello, a reader surgical graphics and computing at Imperial College London, told Jessica Hamzelou at New Scientist. "It means the team will have much more information about organs and their structuring."

The virtual female will help enable the Visible Human Project's original goal – a body proxy for the purposes of medical education – but will also let researchers study other things, such as running virtual experiments that are too dangerous to conduct in the real world with living human subjects. In addition to the safety factor, the existence of the virtual human could lead to massive benefits when it comes to cost and practicality issues.

"The phantom gives us a great opportunity to study human tissues without having to do human studies, which are lengthy and expensive," said Ara Nazarian, an orthopaedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School. "Creating the phantom took a lot of work, but now anyone can run an experiment on their laptop."