It's no secret that the world's oceans are struggling with plastic pollution and rising temperatures, but hidden below the surface is a very serious problem - the ocean is running out of oxygen, and fast, according to the most comprehensive study of the ocean's 'dead zones' to date.

Dead zones are vast patches of water that contain low or zero oxygen, and they're a serious problem because, as their name suggests, most marine life suffocates and dies if they're unlucky enough to find themselves in one.

The new study reviewed evidence on low-oxygen zones collected around the world, and found that these deadly swathes of water in the open ocean have quadrupled in number since the 1950s, expanding by millions of square kilometres. And that's a much bigger problem than most people recognise.

"Oxygen is fundamental to life in the oceans," said Denise Breitburg, lead author and marine ecologist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. She's part of the GO2NE (Global Ocean Oxygen Network), which was founded in 2016 to tackle this problem.

"The decline in ocean oxygen ranks among the most serious effects of human activities on Earth's environment."

While scientists have long been aware of these dead zones, this is the first review paper to take such a broad, global view of the issue. And the results aren't pretty.

If the problem in the open ocean isn't bad enough, closer to shore, things are even worse - dead zones in coastal water bodies such as estuaries and seas have increased more than 10-fold since the '50s.

As Earth's climate continues to warm, the team predicts that the oceans will continue to lose oxygen at a rapid pace.

And, as the paper in the journal Science points out: "Major extinction events in Earth's history have been associated with warm climates and oxygen-deficient oceans."

So what's causing these dead zones?

Climate change is a huge part of the problem, especially for the open ocean. Because warm water holds less oxygen, as surface water temperatures warm up, it makes it harder for oxygen to get down into the depths of the ocean.

Closer to shore, nutrient pollution - such as the runoff from agricultural practises - is also playing a big role.

Nutrients like phosphorous from fertiliser can easily end up in rivers and estuaries, which creates algal blooms that drain oxygen from the water as they die and decompose.

It's no surprise then that scientists are worried about the algae bloom the size of Mexico in the Arabian Sea.

Unfortunately, as the oceans get warmer, marine life actually needs more oxygen to survive, not less. The result is huge patches of bleached coral and dead marine life.

These bleached corals and dead crabs are just one example of what happens as the ocean loses oxygen. A new team of scientists is banding together to help the ocean breathe easy again. https://t.co/LKd5wPTzQk pic.twitter.com/AvAgGpiArv

— SmithsonianEnv (@SmithsonianEnv) January 4, 2018

"Approximately half of the oxygen on Earth comes from the ocean," said Vladimir Ryabinin, executive secretary of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission that formed the GO2NE.

"However, combined effects of nutrient loading and climate change are greatly increasing the number and size of 'dead zones' in the open ocean and coastal waters, where oxygen is too low to support most marine life."

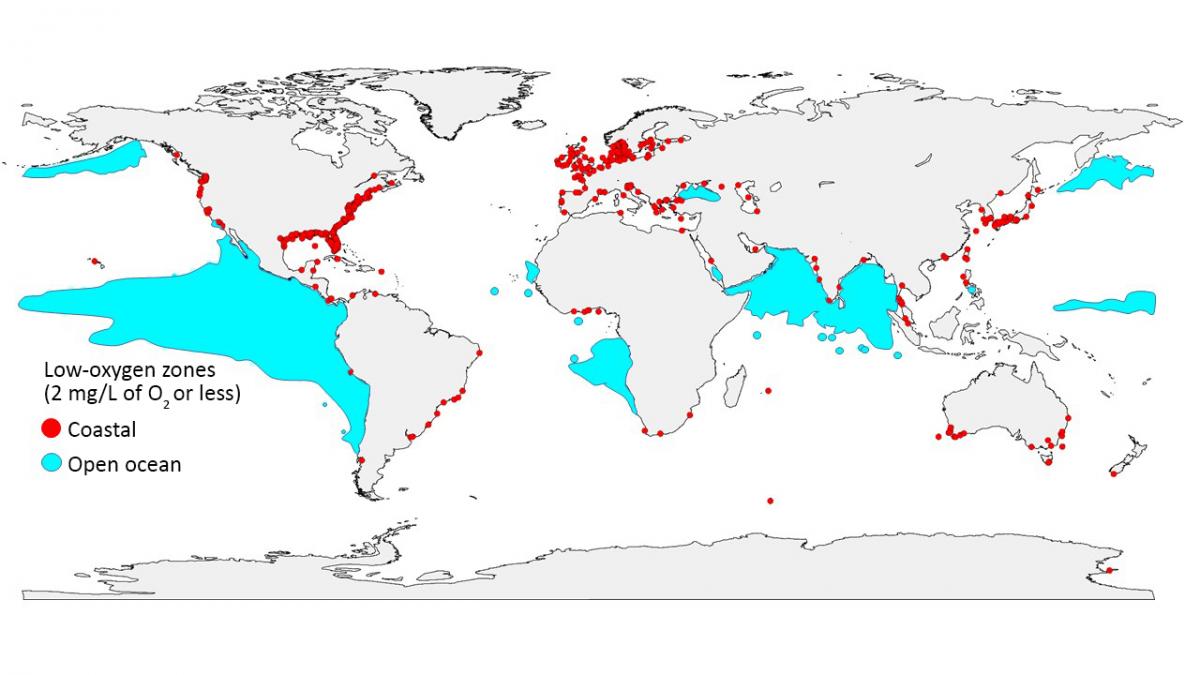

You can see some of these major dead zones in the map below:

(GO2NE working group)

(GO2NE working group)

In known dead zones, such as the Gulf of Mexico, oxygen can drop so low that many animals in the water suffocate and die. While a few species survive, overall, biodiveristy plummets in these areas.

Fish are lucky enough to be able to avoid these zones, but that still poses a major problem as this shrinks their habitat and puts them in more danger from predators.

Even if oxygen isn't so low that it kills animals, it can still stunt growth, hinder reproduction, or trigger disease, according to the researchers.

Oh, and if that's not bad enough, low oxygen also can trigger the release of dangerous chemicals from the ocean, such as nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas up to 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.

The good news is that the GO2NE is focussed on finding ways to fix the problem, and in their study they propose a three-part plan: tackling climate change and nutrient pollution; protecting the most vulnerable marine life; and better monitoring low-oxygen tracking around the world.

"This is a problem we can solve," said Breitburg.

"Halting climate change requires a global effort, but even local actions can help with nutrient-driven oxygen decline."

She uses the example of Chesapeake Bay, which once contained a huge dead zone, but thanks to improved sewage treatment and better farming practices almost has no zero oxygen water left.

"Tackling climate change may seem more daunting," she added, "but doing it is critical for stemming the decline of oxygen in our oceans, and for nearly every aspect of life on our planet."

The research has been published in Science.