Our ancestors are known to have gotten frisky with other, now-extinct species of humans, leaving traces in our DNA to this day. A new analysis has found that a certain genetic variant inherited from the Denisovans may have given modern humans (Homo sapiens) an edge in populating the American continents.

"Typically, genetic novelty is generated through a very slow process," says evolutionary biologist Emilia Huerta-Sánchez, from Brown University in the US. "But these interbreeding events were a sudden way to introduce a lot of new variation."

Related: We Just Got Even More Evidence of Humans Interbreeding With Mysterious Denisovans

The MUC19 region of the human genome codes for a mucin protein – which, as the name suggests, is involved in the formation of mucus, the gel-like substance our cells secrete to build and lubricate our bodies.

We all have MUC19 genes, but it turns out people with Indigenous American ancestry are more likely than other populations to have a particular variant of this gene that can be traced back to the ancient, now-extinct Denisovans.

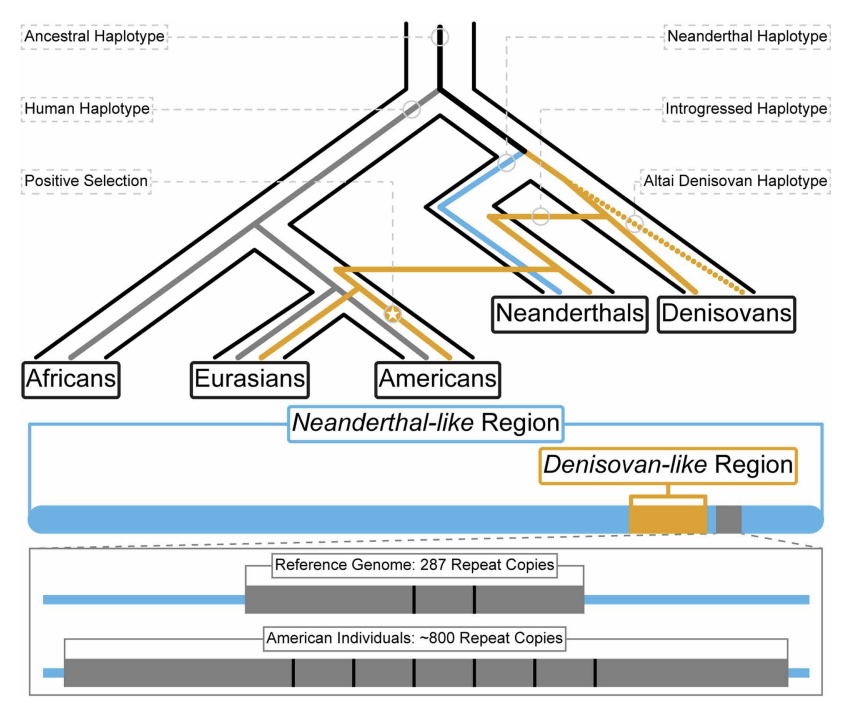

After close analysis of ancient and modern genes, Huerta-Sánchez and colleagues found this variant did not arrive in our DNA directly: it took a meandering path that allowed it to survive far beyond the human species from which it originated.

"Our results point to a complex pattern of multiple introgression events, from Denisovans to Neanderthals and Neanderthals to modern humans, which may have later played a distinct role in the evolutionary history of Indigenous American populations," the authors write.

This explains how a gene associated with a species of ancient humans that we know lived in Tibet and Siberia came to reach such a distant continent, even though it seems the Denisovans themselves never did.

The Denisovan chunk of DNA appeared at the highest frequencies within the genomes of 23 ancient Indigenous American individuals, found at archaeological sites in Alaska, California, and Mexico. These remains pre-date the arrival of Europeans and Africans to the continent.

Based on data collected as part of the 1,000 Genomes Project, a worldwide survey of human genetic variation, the authors found that contemporary Latino Indigenous Americans also have this signature Denisovan gene at high frequencies.

Using a number of statistical tests, the team also revealed that as Homo sapiens migrated into North America, they experienced a massive expansion of repeated sequences within the MUC19 region of their genomes.

According to the authors, this expansion "effectively doubles the functional domain of this mucin, indicating an adaptive role driven by environmental pressures particular to the Americas."

Related: Ancient Humans Had Sex With More Than Just Neanderthals, Scientists Find

This repetition occurred in a region that determines the protein's ability to bind to sugars, allowing it to form a stickier version of the mucin glycoprotein.

Making their mucus stickier must have offered some benefit that improved the success of survival and reproduction in these new environments, the team says.

It's tricky to pin down exactly what that benefit may be, but the authors note that some other mucin genes, like MUC7, feature variants that have different microbe-binding properties, which are crucial for host-microbe symbiosis like that which occurs in our guts, mouths, and nether-regions.

Perhaps the Denisovan-like genes allowed humans to cooperate with a beneficial North American microbe, or perhaps they helped to reject harmful ones.

"Something about this gene was clearly useful for these populations – and maybe still is or will be in the future," Huerta-Sánchez says. "We hope that leads to additional study of what this gene is actually doing."

This research is published in Science.