You won't find visits to the dentist at the top of most people's lists of fun activities, but check-ups could be made easier by a gel that repairs and replaces damaged tooth enamel.

This is the work of an international team led by researchers at the University of Nottingham in the UK, and it has the potential to fill a gap in our extremely limited regenerative capabilities: We can't naturally regrow tooth enamel once it has decayed away, but replacing this protective covering on damaged teeth could help prevent tooth decay.

Like some previous attempts to regrow enamel, this new gel mimics how tooth enamel gets laid down in the first place. The new solution can fill in cracks in teeth, and be applied on top of bare, exposed dentine (the bone-like bulk of a tooth, below the enamel).

Related: 'Toothpick Grooves' in Neanderthal Teeth Aren't What We Thought

"When our material is applied to demineralized or eroded enamel, or exposed dentine, the material promotes the growth of crystals in an integrated and organized manner, recovering the architecture of our natural healthy enamel," says pharmaceutical scientist Abshar Hasan of the University of Nottingham in the UK.

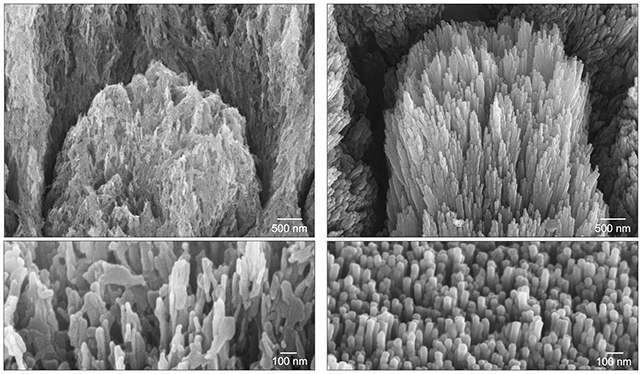

When enamel grows for the first time, it does so via a scaffold made by natural proteins called amelogenin. Here, the researchers attempted to replicate that scaffolding using proteins called elastin-like recombinamers or ELRs.

This synthetic scaffolding then works like the natural equivalent, encouraging the growth of new enamel through a process known as epitaxial mineralization. New enamel crystals form from calcium and phosphate in saliva, or, in the case of these lab experiments, in a solution added to extracted teeth after the scaffold has been built up.

Crucially, the new crystals are seamlessly aligned with the crystals in whatever part of the natural dentine or enamel remains. Furthermore, the resulting enamel shows signs of being just as strong as the material it's replacing.

"We have tested the mechanical properties of these regenerated tissues under conditions simulating real-life situations – such as tooth brushing, chewing, and exposure to acidic foods – and found that the regenerated enamel behaves just like healthy enamel," says Hasan.

Tooth decay is such a big health problem that for years scientists have been testing and developing ways to replace worn enamel, including the use of liquids and peptides. One day we might even be able to grow entire teeth in laboratory settings, ready for transplanting into mouths.

This stands out as one of the most promising developments so far though. It's easy and quick to apply – ultimately, a dentist could do it – and it outperforms the other options currently available for this kind of process, according to the researchers, who have founded a start-up to further their research.

However, this still needs to be carefully tested in actual human mouths rather than just the lab so the researchers can determine whether it's safe. That's something they want to address in the future.

"These results suggest that our technology could potentially provide a one-pot solution for the regeneration of dental enamel independently of the level of tooth erosion," the researchers conclude.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.