For the first time, surgeons have successfully repaired a major malformation in the brain of a fetus.

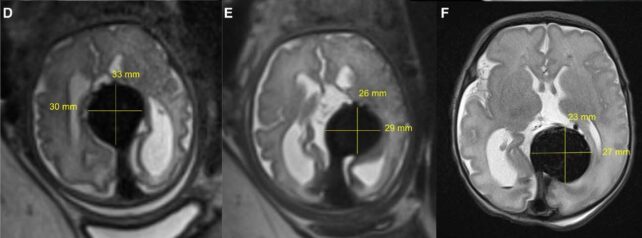

Guided by ultrasound, surgeons from Boston Children's Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital in the US used a surgical technique called embolization to treat a rare prenatal condition. Called vein of Galen malformation, the vascular abnormality permits blood to flow dangerously fast through part of the brain after the child is born. The success of the procedure offers new hope for treating the condition before the risk of complications escalates.

Although this is just the first patient to be treated this way, the procedure appears to have been a resounding win.

"In our ongoing clinical trial, we are using ultrasound-guided transuterine embolization to address the vein of Galen malformation before birth, and in our first treated case, we were thrilled to see that the aggressive decline usually seen after birth simply did not appear," says Darren Orbach, a neurointerventional radiologist from Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

"We are pleased to report that at six weeks, the infant is progressing remarkably well, on no medications, eating normally, gaining weight and is back home. There are no signs of any negative effects on the brain."

Affecting around 1 in 60,000 infants, vein of Galen malformation is a rare type of vascular abnormality in the brain that causes arteries to connect directly with the veins rather than the capillaries, which would otherwise control the flow of blood. This means that the flow of blood into the veins is much higher than is safe, with a number of deleterious effects.

The condition places significant stress on the cardiovascular system, which can lead to heart failure. It can cause hypertension in the arteries in the lungs and heart. And because of the additional pressure in the brain, it can cause significant brain damage that results in neurological and cognitive impairment. It also has a high mortality rate.

It's usually treated after birth with embolization, a technique in which surgeons place specialized material in the vein to block it, such as a clotting agent that helps the blood to coagulate and thus prevent the blood from flowing.

But the condition can rapidly change for the worse after birth. The low resistance of the placenta helps regulate blood flow and blood pressure, giving the fetus some protection that it loses when it is born. Soon after birth, a small blood vessel that connects a lung artery to the aorta closes, which also adds to the pressure in the arteries of the lungs.

Orbach and his colleagues are therefore undertaking a clinical trial to gauge the possibility of treating the condition prior to birth. Their patient was a fetus at 34 weeks and 2 days gestation (full term is around 40 weeks), and they used ultrasound to guide them as they performed the embolization procedure.

The infant was subsequently induced two days later, since the procedure had resulted in the premature rupture of membranes in the uterus. However, once the baby was born, its cardiovascular system seemed to be working normally, and it required no additional support or surgery. Because the birth was premature, the infant had to remain in the hospital's NICU unit for several weeks, during which time the doctors continued to monitor its brain.

They saw no signs at all of neurological malfunction, fluid build-up or bleeding, and mother and babe were given the all-clear and sent home.

Because this is the first patient in an ongoing clinical trial, the technique is nowhere near ready for widespread application. One successful case is not enough to establish a pattern of success. Future cases may not proceed so smoothly; whether the benefits outweigh the risks of the procedure is yet to be determined.

"As always, a number of these fetal cases will need to be performed and followed in order to establish a clear pattern of improvement in both neurologic and cardiovascular outcomes," says cardiologist Gary Satou of the UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital, who was not involved in the study. "Thus, the national clinical trial will be crucial in order to achieve adequate data and, hopefully, successful outcomes."

But the results are highly promising. At time of writing, the infant was continuing to thrive, suggesting that, for some patients at least, prenatal surgery could be a lifeline.

"While this is only our first treated patient and it is vital that we continue the trial to assess the safety and efficacy in other patients, this approach has the potential to mark a paradigm shift in managing vein of Galen malformation where we repair the malformation prior to birth and head off the heart failure before it occurs, rather than trying to reverse it after birth," Orbach says.

"This may markedly reduce the risk of long-term brain damage, disability or death among these infants."

The team's results have been published in Stroke.