Astronomers have confirmed the earliest, most distant black hole yet – and it's surprisingly monstrous for its time.

Residing in a galaxy called CAPERS-LRD-z9, it was already approximately 300 million times the mass of the Sun just 500 million years after the Big Bang, when the baby Universe was just 3 percent of its current age.

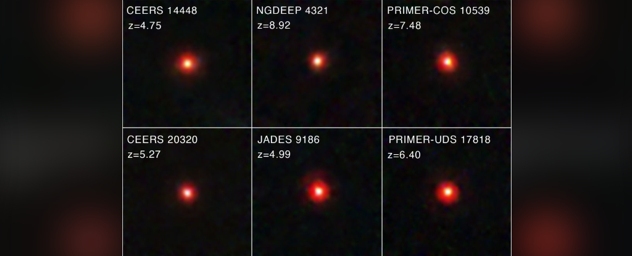

Additionally, this discovery sheds literal light on an ancient, mysterious class of celestial objects called Little Red Dots (LRDs), which are perplexingly bright, small, red objects in the early Universe. They appear around 600 million years after the Big Bang, then start disappearing less than a billion years later.

LRDs have only recently been revealed by JWST's unprecedented infrared ability to explore Cosmic Dawn, the universe's earliest epochs. These are also the Universe's reddest epochs, as the light reaching JWST has been stretched to ever-redder wavelengths on its long journey through the expanding fabric of spacetime.

Related: 36 Billion Suns: Record Black Hole Discovery Could Be as Big as They Get

The newly confirmed supermassive black hole at the heart of CAPERS-LRD-z9 is known as an active galactic nucleus (AGN), the bright, rapidly feeding black hole at the center of a galaxy. It appears red because it's enveloped in a glowing cocoon of gas and dust, which may make it a science-fiction-sounding "black hole star."

The gravity of this supermassive black hole is whipping the gas around it to mind-boggling speeds of around 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) per second, or 1 percent the speed of light. These gassy winds are what help astronomers reveal the presence of black holes via spectroscopy.

"There aren't many other things that create this signature," explains lead author Anthony Taylor, astrophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Spectroscopy splits incoming light into its wavelengths to yield a spectrum that reveals information about an object. In this case, the light waves from the gas around the black hole gets stretched and turns redder when it moves away from an observer. Conversely, light becomes compressed and bluer when it's moving toward an observer. These changes reveal an object's velocity.

Importantly, the spectroscopic confirmation of CAPERS-LRD-z9 supports the idea that LRDs contain supermassive black holes, with "supermassive" being an understatement: some reach 10 million solar masses within their first billion years. For comparison, the supermassive black hole at the core of the Milky Way is about 4 million solar masses.

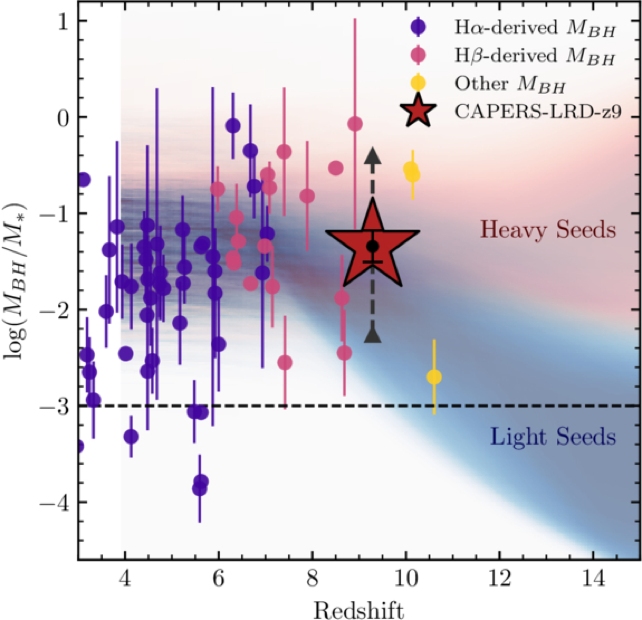

The black holes at the heart of LRDs may not just be supermassive, but "overmassive," with mass ratios approaching 10 percent to 100 percent of their host galaxy's stellar mass.

Specifically, at up to around 300 million solar masses, the supermassive black hole in CAPERS-LRD-z9 has the equivalent of about half the mass of all the stars in its galaxy. By contrast, more local galaxies may have central black holes that are only about 0.1 percent of their stellar mass.

For added size perspective, CAPERS-LRD-z9 is so compact that not even JWST can resolve it. It seems to be, at most, 1,140 light-years wide – in the realm of the dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way.

The researchers say that there are two ways for a black hole to grow so massive within just 500 million years of cosmic time. Both start with a big, heavy "seed" black hole growing at different rates.

If it's growing at the theoretical upper limit of black hole growth, known as the Eddington rate, the seed might have started with around 10,000 solar masses.

Or, it could have started off much smaller, at just 100 solar masses. That seed would have to grow even faster, at the super-Eddington rate, force-fed by gravity and the thick, dense envelope of gas around it.

The seeds themselves may originate as primordial black holes produced when the Big Bang, well, banged. They may also form from the collapse of Population III stars (the elusive first stars to illuminate the cosmos), from "runaway collisions" in dense star clusters, or from the direct collapse of immense, primordial gas clouds.

Overall, it's difficult to peer much farther in spacetime: "When looking for black holes, this is about as far back as you can practically go. We're really pushing the boundaries of what current technology can detect," adds Taylor.

Finally, this research adds evidence that LRDs were an ephemeral phenomena in the early universe, and potentially an initial step in galactic evolution that may have birthed the Milky Way itself.

This research is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.