As far back as 20,000 years ago, humans living around the Bay of Biscay were crafting a variety of whale bones into tools, new research has revealed.

A careful study of artifacts that have spent years tucked away in museum collections across Europe shows that the Magdalenian culture not only worked and used the bones of our planet's largest living beasts, they did so from a range of species, long before they were capable of actively hunting them.

This discovery not only gives is crucial insight into the Magdalenians, but also reveals information about the changing ecology of the Bay of Biscay, off the coast of France and Spain.

"I am an archaeologist more accustomed to terrestrial faunas. I am used to excavating cave sites in the foothills of the Pyrenees, and I work on the Magdalenian period which yielded a well-known cave art showing mostly ungulates (horse, bison, cervids, etc.)," University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès archaeologist and senior author Jean-Marc Pétillon told ScienceAlert.

"The most exciting thing for me is to shed light on how much the sea, and the sea animals, might also have been important for the people at that time."

The Magdalenian culture occupied coastal and inland regions of western Europe flourished some 19,000 to 14,000 years ago as the world was reaching the end of the last glacial period. They left behind a relatively rich archaeological record, but with limitations.

Ancient coastal habitats are particularly prone to the ravages of time and the ocean, and most of the record of the use of coastal resources comes from inland, where artifacts had been transported.

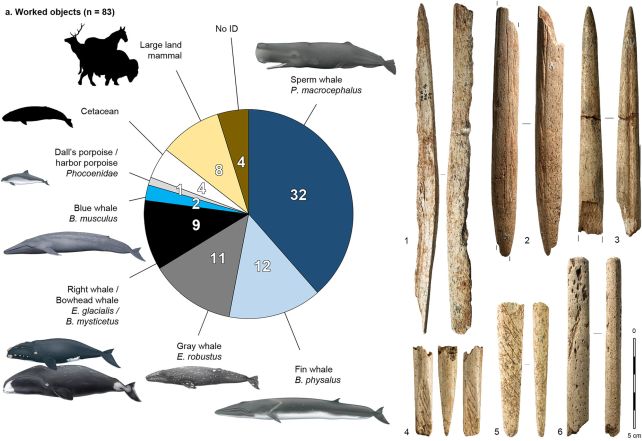

It's from these inland sites that archaeolologists excavated the Magdalenian artifacts: "more than 150 tools and projectile heads made of whale bone presumably of Atlantic origin, mostly found scattered from Asturias to the central part of the northern Pyrenean range," writes a team led by Krista McGrath of the Autonomous University of Barcelona and Laura G. van der Sluis of the University of Vienna.

Hunting and seafaring techniques to prey on whales would not emerge until thousands of years later, so the bones would have been gleaned opportunistically from whales stranding themselves on the seashore. The Magdalenians then used the foraged material to craft tools – mostly projectile points, Pétillon explained.

"The main raw material used to manufacture the points at that period is antler (from reindeer or red deer), because it is less brittle and more pliable than land mammal bone," he said.

"The fact that some points are made of whale bone shows that this material was preferred over antler in certain cases. It is probably because of its large dimensions: some of our whale bone points were more than 40 centimeters [16 inches] long, which is difficult to get with antler."

To learn more about the timing and use of whale bone as a material, the researchers turned to two relatively modern techniques: a paleoproteomics method that analyzes collagen peptides in ancient samples to identify species; and micro-carbon dating, which is a variation of radiocarbon dating that requires less material.

By carefully using these techniques on their samples, the researchers dated the bone tools to between 16,000 and 20,000 years ago. At least five different species of large whales contributed their bones to Magdalenian technology – which tells us about the ecology of the region during the last glacial period.

"Our study shows that there was a large diversity of whale species in the Gulf of Biscay, northeastern North Atlantic, at that period. Most of the species we identified (sperm whale, blue whale, fin whale) are present in the North Atlantic today; in this perspective, their presence is not surprising," Pétillon said.

"What was more surprising to me – as an archaeologist more accustomed to terrestrial faunas – was that these whale species remained the same despite the great environmental difference between the Late Pleistocene and today. In the same period, continental faunas are very different: the ungulates hunted include reindeer, saiga antelopes, bison, etc., all disappeared from Western Europe today."

Interestingly, analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes absorbed from the environment as the animals fed show that these whales had a slightly different diet from those of the same species that are around today.

It's impossible to determine what exactly this means – perhaps migration patterns were different, or food availability – but it does show a level of adaptability to changing circumstances, whatever those were.

The presence of the whales in the Bay of Biscay would have been a draw for the Magdalenian culture, the researchers believe, offering a resource opportunity too good to pass up. Although whale strandings may not have been a frequent occurrence, they would have contributed to the list of benefits coastal living would have had to offer, playing a role in human mobility patterns in the region.

It's a fascinating, multi-layered result that underscores the value of revisiting previously collected objects and seeing what new information we can discover with new techniques.

"Even old collections, excavated more than one century ago with field methods now outdated, and stored in museums for a long time, can bring new scientific information when approached with the right analytical tools," Pétillon said.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.