All over the world, fresh water is disappearing, and a new analysis reveals that much of it is entering the ocean, with drying continents now contributing more to the alarming rise in global sea levels than melting ice sheets.

The research team, led by Earth system scientist Hrishikesh Chandanpurkar from FLAME University in India, says that urgent action is required to prepare for much drier times ahead, thanks to climate change and human groundwater depletion.

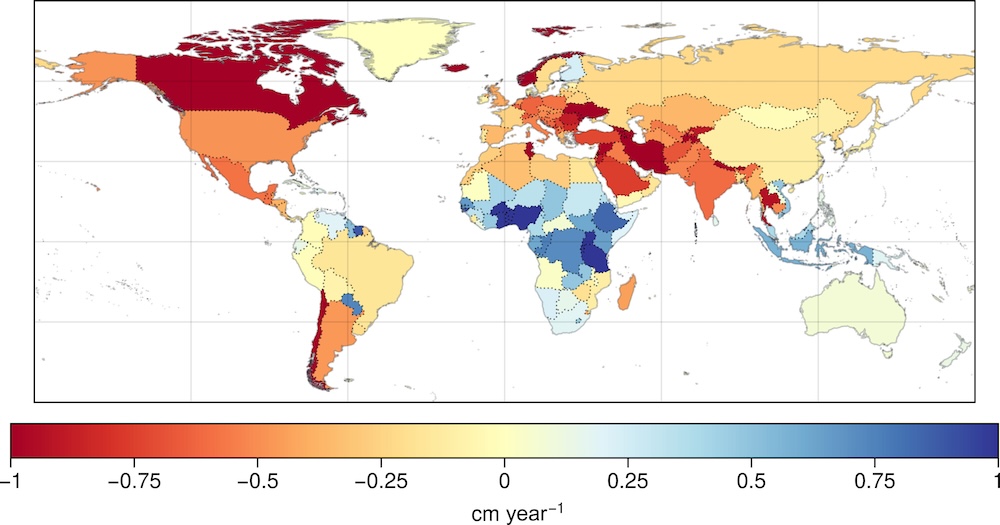

Using more than two decades of satellite observations from NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment and its follow-on mission, the researchers created a picture of how terrestrial water storage has changed since 2002, and why.

Related: Our Atmosphere's Growing Thirst Is a Hidden Cause of Worsening Droughts

"We find that the continents (all land excluding Greenland and Antarctica) have undergone unprecedented rates of drying and that the continental areas experiencing drying are increasing by about twice the size of the state of California each year," the authors write.

Humans have majorly disrupted Earth's water cycle by emitting greenhouse gases that change our atmosphere, and diverting waterways and rainfall catchments. Although 'wet' areas have been getting wetter, and 'dry' areas have been getting drier, these shifts aren't keeping step.

"Dry areas are drying at a faster rate than wet areas are wetting," the team writes. "At the same time, the area experiencing drying has increased, while the area experiencing wetting has decreased."

This means terrestrial water is, on the whole, diminishing, with devastating effects worldwide. That includes freshwater sources on the surface, like lakes and rivers, and also groundwater stored in aquifers deep below Earth's surface. The majority of the human population – 75 percent of us – live in the 101 countries where fresh water is being lost at increasing rates.

Where has it all gone? The ocean, mostly. Enough fresh water is being displaced from the continents that it is now contributing more to sea level rise than ice sheets.

This net shift towards continental drying is driven largely by terrestrial water loss in high-latitude areas like Canada and Russia (regions we don't usually think of as 'dry'), which the authors suspect is due to the melting ice and permafrost in these regions.

In continents without glaciers, 68 percent of the loss of terrestrial water supply can be attributed to human groundwater depletion. Recent and unprecedented extreme droughts in Central America and Europe have also played a part, and events like these are only expected to become more frequent and severe with the climate crisis.

As our growing fossil fuel emissions alter the patterns of rainfall that we once relied on, people are turning in desperation to groundwater, which is putting further pressure on these water sources, which are not being replenished at the rate they are drained.

On many continents, overuse of groundwater could be traced to dry agricultural regions that rely on this water source to irrigate crops: for instance, California's Central Valley, which produces 70 percent of the world's almonds, and cotton production near the now totally-dry Aral Sea in Central Asia.

"At present, overpumping groundwater is the largest contributor to rates of terrestrial water storage decline in drying regions, significantly amplifying the impacts of increasing temperature, aridification, and extreme drought events," the authors write.

"Protecting the world's groundwater supply is paramount in a warming world and on continents that we now know are drying."

They hope regional, national, and international efforts to develop sustainable uses of groundwater can help preserve this precious resource for many years to come.

"While efforts to slow climate change may be sputtering, there is no reason why efforts to slow rates of continental drying should do the same," the team writes.

This research was published in Science Advances.