The most high-resolution map yet of the underlying geology beneath Earth's Southern Hemisphere reveals something we previously never knew about: an ancient ocean floor that may wrap around the core.

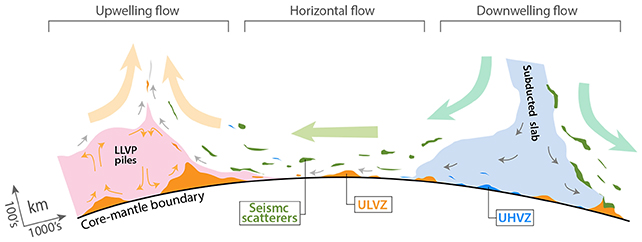

This thin but dense layer exists around 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) below the surface, according to a study published in April. That depth is where the molten, metallic outer core meets the rocky mantle above it. This is the core-mantle boundary (CMB).

"Seismic investigations, such as ours, provide the highest resolution imaging of the interior structure of our planet, and we are finding that this structure is vastly more complicated than once thought," said geologist Samantha Hansen from the University of Alabama when the findings were announced.

Understanding exactly what's beneath our feet – in as much detail as possible – is vital for studying everything from volcanic eruptions to the variations in Earth's magnetic field, which protects us from the solar radiation in space.

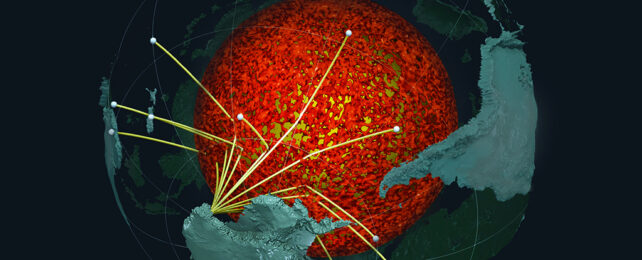

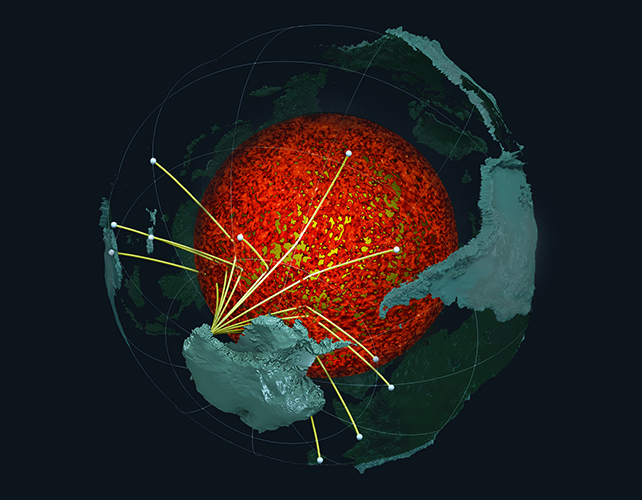

Hansen and her colleagues used 15 monitoring stations buried in the ice of Antarctica to map seismic waves from earthquakes over three years. The way those waves move and bounce reveals the composition of the material inside Earth. Because the sound waves move slower in these areas, they're called ultralow velocity zones (ULVZs).

"Analyzing [thousands] of seismic recordings from Antarctica, our high-definition imaging method found thin anomalous zones of material at the CMB everywhere we probed," said geophysicist Edward Garnero from Arizona State University.

"The material's thickness varies from a few kilometers to [tens] of kilometers. This suggests we are seeing mountains on the core, in some places up to five times taller than Mt. Everest."

According to the researchers, these ULVZs are most likely oceanic crust buried over millions of years.

While the sunken crust isn't close to recognized subduction zones on the surface – zones where shifting tectonic plates push the rock down into Earth's interior – simulations reported in the study show how convection currents could have shifted the ancient ocean floor to its current resting place.

It's tricky to make assumptions about rock types and movement based on seismic wave movement, and the researchers aren't ruling out other options. However, the ocean floor hypothesis seems the most likely explanation for these ULVZs right now.

There's also the suggestion that this ancient ocean crust could be wrapped around the entire core, though as it's so thin, it's hard to know for sure. Future seismic surveys should be able to add further to the overall picture.

One of the ways the discovery can help geologists is in figuring out how heat from the hotter and denser core escapes up into the mantle. The differences in composition between these two layers are greater than they are between the solid surface rock and the air above it in the part we live on.

"Our research provides important connections between shallow and deep Earth structure and the overall processes driving our planet," said Hansen.

The research has been published in Science Advances.

An earlier version of this article was published in April 2023.