In May, NASA scientists said the Voyager 1 spacecraft was sending back inaccurate data from its attitude-control system. The mysterious glitch is still ongoing, according to the mission's engineering team.

Now, in order to find a fix, engineers are digging through decades-old manuals.

Voyager 1, along with its twin Voyager 2, launched in 1977 with a design lifetime of five years to study Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and their respective moons up close.

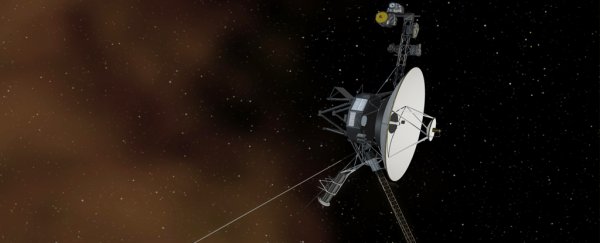

After nearly 45 years in space, both spacecraft are still functioning. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the very first human-made object to venture beyond the boundary of our sun's influence, known as the heliopause, and into interstellar space. It's now around 14.5 billion miles from Earth and sending data back from beyond the solar system.

"Nobody thought it would last as long as it has," Suzanne Dodd, project manager for the Voyager mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Insider, adding, "And here we are."

Unearthing old spacecraft documents

Voyager 1 was designed and built in the early 1970s, complicating efforts to troubleshoot the spacecraft's problems.

Though current Voyager engineers have some documentation – or command media, the technical term for the paperwork containing details on the spacecraft's design and procedures – from those early mission days, other important documents may have been lost or misplaced.

During the first 12 years of the Voyager mission, thousands of engineers worked on the project, according to Dodd.

"As they retired in the '70s and '80s, there wasn't a big push to have a project document library. People would take their boxes home to their garage," Dodd added. In modern missions, NASA keeps more robust records of documentation.

There are some boxes with documents and schematic stored off-site from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Dodd and the rest of Voyager's handlers can request access to these records. Still, it can be a challenge.

"Getting that information requires you to figure out who works in that area on the project," Dodd said.

For Voyager 1's latest glitch, mission engineers have had to specifically look for boxes under the name of engineers who helped design the attitude-control system. "It's a time consuming process," Dodd said.

Source of the bug

The spacecraft's attitude-control system, which sends telemetry data back to NASA, indicates Voyager 1's orientation in space and keeps the spacecraft's high-gain antenna pointed at Earth, enabling it to beam data home.

"Telemetry data is basically a status on the health of the system," Dodd said. But the telemetry readouts the spacecraft's handlers are getting from the system are garbled, according to Dodd, which means they don't know if the attitude-control system is working properly.

So far, Voyager engineers haven't been able to find a root cause for the glitch, mainly because they haven't been able to reset the system, Dodd said. Dodd and her team believe it's due to an aging part. "Not everything works forever, even in space," she said.

Voyager's glitch may also be influenced by its location in interstellar space. According to Dodd, the spacecraft's data suggests that high-energy charged particles are out in interstellar space.

"It's unlikely for one to hit the spacecraft, but if it were to occur, it could cause more damage to the electronics," Dodd said, adding, "We can't pinpoint that as the source of the anomaly, but it could be a factor."

Despite the spacecraft's orientation issues, it's still receiving and executing commands from Earth and its antenna is still pointed toward us.

"We haven't seen any degradation in the signal strength," Dodd said.

Voyager 1's journey continues

As part of an ongoing power management effort that has ramped up in recent years, engineers have been powering down non-technical systems on board the Voyager probes, like its science instruments heaters, hoping to keep them going through 2030.

From discovering unknown moons and rings to the first direct evidence of the heliopause, the Voyager mission has helped scientists understand the cosmos.

"We want the mission to last as long as possible, because the science data is so very valuable," Dodd said.

"It's really remarkable that both spacecraft are still operating and operating well – little glitches, but operating extremely well and still sending back this valuable data," Dodd said, adding, "They're still talking to us."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: