Some of the very first sea creatures to be able to walk didn't make the most of their new evolutionary advantage and stayed in the oceans, according to new research, which suggests the ability to walk originated much earlier than previously thought.

The research is based on a genetic analysis of the brain cells of the little skate fish (Leucoraja erinacea), one of the most primitive animals with a backbone.

It turns out the brain systems controlling its movement are very similar to those found in mammals. That suggests these sea creatures were the first to learn some kind of walking-like behaviour.

The team of scientists also recorded footage of little skate embryos making walking-like movements along the bottom of a fish tank, movements that have been seen in previous observations:

"The nerve networks needed for walking were thought to be unique to land animals that transitioned from fishes around 380 million years ago," says one of the team, Catherine Boisvert from Curtin University in Australia.

"But our research has uncovered that the little skate and some basal sharks already had those neural networks in place."

The little skate is the last common ancestor of sharks and mammals, and that genetic history is important here. Scientists compared the gene expressions with genes activated in the elephant shark and the catshark, showing they'd been preserved through time.

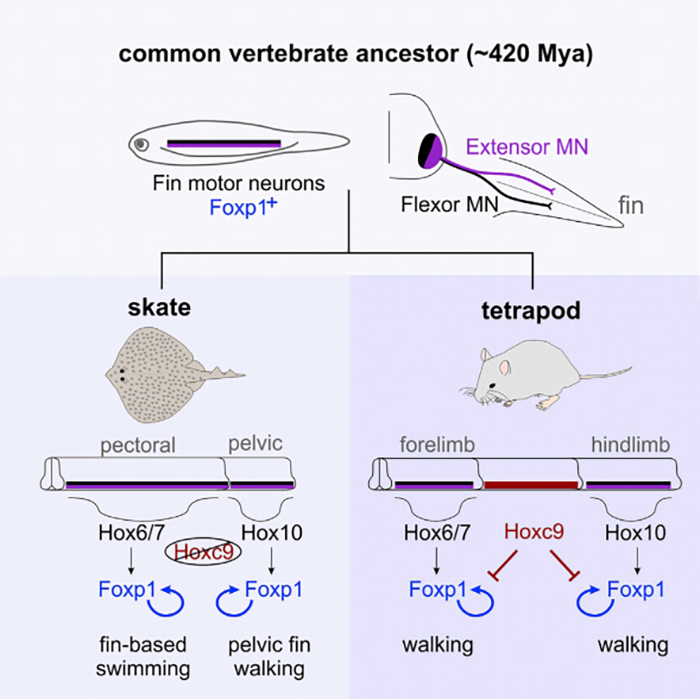

So the walking motions we see in the little skate today may stretch back more than 400 million years.

RNA sequencing also showed that these genetic blueprints – for controlling limbs, muscles, and the bending and straightening of limbs – could be linked between the little skate and mammals.

That pushes back the estimated time of the first land walkers by about 50 million years – not an insignificant period of time.

The little skate doesn't have legs, but it does have two sets of fins. The large pectoral fins are used for swimming, but the smaller pelvic fins allow it to walk along the bottom of the ocean, with alternating left-and-right motions.

Those types of movements, known as ambulatory locomotion, make the fish a very suitable subject for studying the origins of walking.

(Cell)

(Cell)

"It has generally been thought that the ability to walk is something that evolved as vertebrates transitioned from sea to land," says one of the researchers, neurobiologist Jeremy Dasen from the New York University School of Medicine.

"We were surprised to learn that certain species of fish also can walk. In addition, they use a neural and genetic developmental program that is almost identical to the one used by higher vertebrates, including humans."

The research goes further than just giving us a new idea of when creatures first learned to walk - the little skate also offers a relatively simple map of how all these motor neurons work inside the brain.

In other words, scientists could glean important information about how we walk, and how motor neuron diseases could be treated, that they can't get from modern-day mammals because there's so much other activity going on inside their brains.

"Given that that skates use many of the same neural circuits that we do to walk, but with six muscles instead of the hundreds we use, the fish provide a simple model to study how the circuits that enable walking are assembled," says Dasen.

That's in the future, but for now it seems the ability to walk was discovered deep in the ocean rather than on land.

What the study doesn't ask is why these little skates didn't use their new-found talents to do some exploring – simple laziness, or maybe a fondness for their underwater homes?

We may never know, but scientists have bigger research fish to fry.

"This research is very significant as the little skate could become a very good model for understanding the development of nerve networks controlling our limbs and also reveal further information about the diseases associated with them," says Boisvert.

The research has been published in Cell.