A patient with type 1 diabetes has begun producing his own insulin after receiving a transplant of pancreatic cells.

For the first time in humans, these islet cells have been genetically edited so they wouldn't be rejected by the patient, removing the need for immunosuppressant drugs.

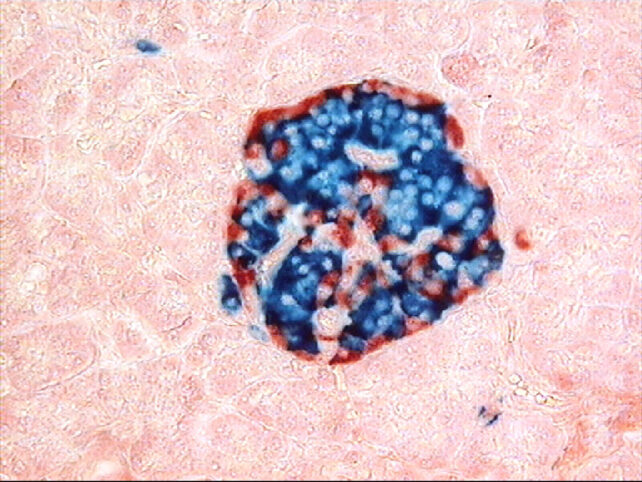

Type 1 diabetes usually begins when the immune system mistakenly attacks the islet cells in the pancreas, which are responsible for producing insulin. The condition is usually managed with a careful diet and regular insulin injections, but an emerging treatment involves replacing the damaged islet cells with functional ones.

Related: New Treatment May Cure Severe Type 1 Diabetes, Study Finds

In a new proof-of-concept study, a 42-year-old male patient, who had had type 1 diabetes since the age of 5, received a transplant of islet cells from a healthy donor. The cells were delivered through a series of injections into the muscle of his forearm.

Over the next 12 weeks, the cells successfully produced insulin in response to glucose spikes, such as after meals. But the most important aspect is that the patient didn't require immunosuppressants.

Normally, the immune system will recognize the transplanted cells as foreign and destroy them, rendering the therapy ineffective. To get around that, patients are given drugs that suppress their immune system. That solution works, but leaves the patients vulnerable to infections and other illnesses.

So, before the cells were implanted, three genetic edits were made using the CRISPR tool. Two edits reduced the amount of particular antigens that adaptive T cells use to identify foreign objects. The third boosted production of a protein called CD47, which in turn blocks innate immune cell responses.

Not all of the gene edits were successful, but in a way that provided an intriguing control group. Cells with no successful edits were killed off by T cells within a few weeks, while those that knocked out the antigen production were still wiped out by natural killer cells and macrophages.

Only those with three successful edits survived, and thankfully there were enough of them in the graft to remain functional.

The technique had previously shown promise in tests in monkeys and mice, but this marks the first time it has been attempted in humans. Similar studies in humans have shown promise, but always with the help of immunosuppressant drugs, which bring their own complications.

Last year, doctors reported that a young woman in China received a transplant of insulin-producing cells grown from her own stem cells. Within four months, her body was able to produce enough insulin to stay within a safe blood glucose range for over 98 percent of the day.

The researchers on the new study say that their method could not only make for more effective, safer treatments for diabetes, but could be applied to other types of cells, reducing the need for immunosuppressants with other transplants.

The research was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.