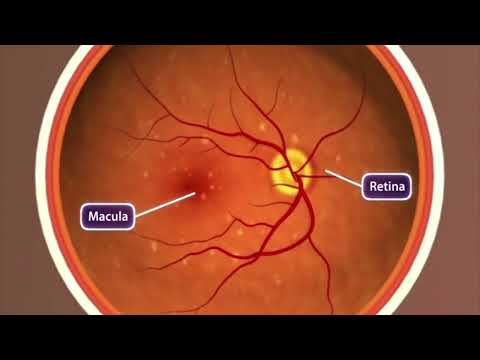

Taking a photo of a friend? You've probably got their face centered and focused. Driving down a highway? Eyes on the road.

But for millions of adults with age-related macular degeneration, that crucial, central field of sight is blurred beyond recognition. Current treatments can only slow its progression or augment vision, but the blur will usually continue to worsen.

A recent clinical trial of a treatment based on stem cell transplants has found the procedure may be able to safely reverse the cumulative damage to the hard-working macula – that part of the retina responsible for all you see directly in front of you.

Related: Gold Injections in The Eye May Be The Future of Vision Preservation

It's the first time this particular stem cell treatment has been tested in humans, and as a phase 1/2a clinical trial, the main focus of the investigation was safety and efficacy.

The effectiveness of the treatment compared with existing therapies won't be known until at least the end of phase 3, but the preliminary results were positive enough that trials are proceeding.

Earlier testing in the lab showed the transplant process was safe enough to proceed with in-human trials: the transplanted stem cells retained their retinal identity, and no tumours or toxicity were observed.

Screening 18 potentially eligible patients, the researchers enrolled six volunteers aged 71 to 86 who had been diagnosed with dry age-related macular degeneration (the most common type, making up around 80 percent of all macular degeneration cases).

Three of the participants had worse vision in general, with visual acuity scores ranging from 20/200 to 20/800 (which means they could only see the first, biggest letter on the Snellen chart, at best). The other three had scores between 20/70 and 20/200.

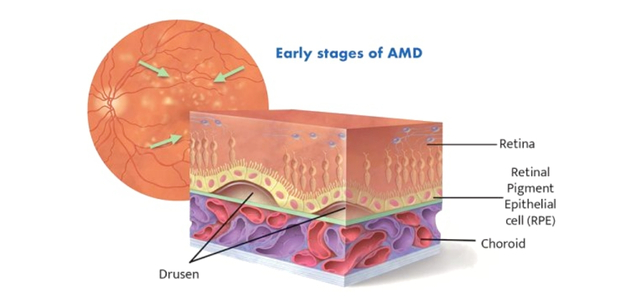

Unlike the less common and more rapid 'wet' macular degeneration, the 'dry' form of the condition is a gradual loss of vision caused by tiny deposits of fats and proteins destroying the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPEs) that support the eye's light-sensitive tissues.

The treatment involves surgically transplanting stem cells sourced from an eye bank that can produce new RPEs.

Each of the trial's participants received a relatively low dose of 50,000 RPE stem cells through a single injection. The cells were inserted under the retina of the superior temporal macula in the patients' most-impaired eye.

Ultimately, the trial showed the treatment is safe, with no sign of the immune problems or tumors that can sometimes arise in stem cell transplants.

No adverse events were related to the stem cells themselves, though there were a few of the typical complications seen in this kind of eye surgery.

Significantly, each patient experienced an improvement in vision in the eye that received the transplant that was not apparent in the other, suggesting the stem cells were doing exactly what scientists had hoped they would.

One year after the treatment, the three participants who had the worst vision were able to see an average of 21 more letters on an eye chart than they had at the start of the trial.

"Although we were pleased with the safety data, the exciting part was that their vision was also improving," says Rajesh Rao, a physician-scientist and ophthalmologist at Michigan Medicine.

"We were surprised by the magnitude of vision gain in the most severely affected patients who received the adult stem cell-derived RPE transplants. This level of vision gain has not been seen in this group of patients with advanced dry AMD."

The trial is continuing to monitor patients who received higher doses (150,000 and 250,000 cells). If those doses are also deemed safe, it will help determine whether Rao and team can scale up human testing.

The research was published in Cell Stem Cell.