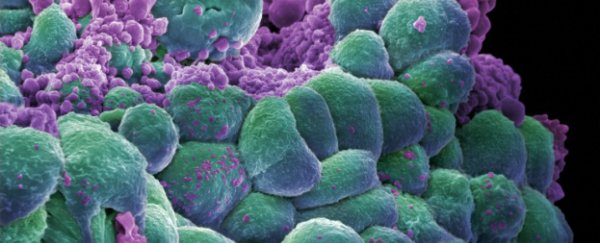

Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a breast cancer vaccine that aims to prime a patient's immune system against the disease. And the first small clinical trials have shown that it's safe in humans, and also suggest that it's working effectively.

The vaccine works by priming a white blood cell in a patient's immune system to target a protein called mammaglobin-A, which is found almost exclusively in breast tissue, and is expressed at abnormally high levels by the majority of breast cancer tumours.

The vaccine has now been tested on 14 patients who already have metastatic breast cancer and whose tumours were known to express mammaglobin-A. The purposes of these Phase I trials were simply to test where the vaccine was safe - but early results also suggest that the vaccine also helped slow the progression of the patients' breast cancer.

"Being able to target mammaglobin is exciting because it is expressed broadly in up to 80 percent of breast cancers, but not at meaningful levels in other tissues," said breast cancer surgeon and senior author William E. Gillanders in a press release.

"In theory, this means we could treat a large number of breast cancer patients with potentially fewer side effects.

The research is published in the current issue of Clinical Cancer Research.

During the study, the 14 patients who were given the vaccine did experience some mild or moderate side effects - eight events were recorded involving rash, tenderness at the vaccination site and mild flu-like symptoms. But no severe or life-threatening side effects occurred.

Many of the patients who were given the vaccine already had weakened immune systems as a result of chemotherapy of their disease being in the advanced stages, but despite this, the vaccine still helped to activate their immune system against the tumours and slowed down the disease's progression.

Out of the 14 patients, around half showed no progression of their cancer one year after receiving the vaccine.

In the control group of 12 similar patients who were unvaccinated, only one-fifth showed no cancer progression at the one-year mark.

Even though the study involved a very small sample size, the difference in those results was still statistically significant.

"Despite the weakened immune systems in these patients, we did observe a biologic response to the vaccine while analysing immune cells in their blood samples," said Gillanders in the release. "That's very encouraging. We also saw preliminary evidence of improved outcome, with modestly longer progression-free survival."

These results also suggest the vaccine could be beneficial even to people who already have breast cancer.

Gillanders and his team are now planning a larger clinical trial involving newly diagnosed breast cancer patients, who in theory should have more active immune systems.

"If we give the vaccine to patients at the beginning of treatment, the immune systems should not be compromised like in patients with metastatic disease," said Gillanders. "We also will be able to do more informative immune monitoring than we did in this preliminary trial. Now that we have good evidence that the vaccine is safe, we think testing it in newly diagnosed patients will give us a better idea of the effectiveness of the therapy."

Unfortunately, the vaccine won't be effective in the smaller group of breast cancer patients whose tumours don't express mammaglobin-A, but these results suggest that once we can identify proteins expressed by particular cancers, we can also find ways to encourage our own system to attack them. And that's a pretty exciting concept.

Source: ScienceDaily