If we're going to get serious about long-term space voyages, then being able to patch up injuries will be essential – and that's no longer a far-off concept.

A cosmonaut on board the International Space Station just engineered human cartilage in the microgravity of space for the first time.

Bioprinters that can produce human tissue already exist on Earth, but they rely on gravity and scaffolds in order to bring cartilage cells together.

The clever part of the new process is using magnetism as a replacement for gravity, inside a bespoke assembly machine.

With the help of magnetism, the effects of microgravity and acceleration can be counteracted, and objects – such as cartilage cells – can be held in place ready for assembly.

While the cells themselves aren't magnetic, the fluid in the assembler is, and that can be used to manipulate the tissue.

Before the experiments on board the ISS, scientists developed mathematical models and computer simulations to investigate the viability of the process, looking at how microgravity might affect the way that cells were assembled.

The team then developed spheroids based on human cartilage cells, which were packaged up and sent to the ISS along with a custom-made magnetic bioassembler.

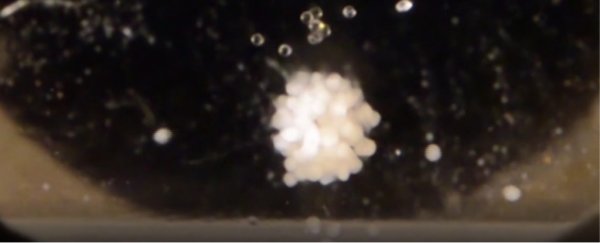

On board the ISS, the crafting process required the cooling of the cartilage spheroids to release them from their hydrogel packaging, before they were put into the bioassembler to be assembled into the correct form, as you can see in the image above.

Cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko performed the experiment.

"People have been doing biological experiments and culturing cells in space, but being able to actually assemble these building blocks into more complex structures using a biomanufacturing tool – that's a first," radiologist Utkan Demirci, from Stanford University, told IEEE Spectrum.

Further down the line, the same magnetic assembly method could even be used to construct materials in space made up of both biological and inorganic materials. We could even be replacing bones while out visiting other planets.

There's a lot more work required to get to that stage though, not least getting this sort of equipment space-ready – delicate instruments and space travel don't really mix well, and machines need to hit a certain level of robustness to survive the trip.

Even with engineering challenges ahead, the study points to methods that could "significantly advance tissue engineering", according to the researchers themselves.

With progress being made in growing meat and fruit out in space too, a trip to Mars is sounding less daunting all the time.

"One could imagine not too far in the future that if we colonise Mars or do long-term space travel, we might want to do experiments where we build functional tissues in space, and test them in extraterrestrial environments," Demirci told IEEE Spectrum.

The research has been published in Science Advances.