Scientists have used the latest gene-editing techniques to find a connection between hands and fins, and discovered a strong evolutionary link between the genes that control the growth of digits (or fingers) and those that control the growth of fins.

The new study is all thanks to a revolutionary new gene-editing technology called CRISPR, which enables scientists to rewrite DNA inside living cells.

CRISPR makes genetic engineering much easier and much cheaper. Some fear it could lead to 'designer babies' that are made to order, but it also has the real potential to treat diseases like never before.

In this case, researchers from the University of Chicago used the technology to highlight a key connection between mice and zebrafish, and the findings could ultimately help us answer the question of how sea creatures evolved to walk on land some 500 million years ago.

"For years, scientists have thought that fin rays were completely unrelated to fingers and toes, utterly dissimilar because one kind of bone is initially formed out of cartilage and the other is formed in simple connective tissue," explains biologist Neil Shubin. "Our results change that whole idea. We now have a lot of things to rethink."

It took three years of gene editing and fate mapping – a method for understanding how cells grow – for team to find a connection between these two types of appendages.

Based on previous studies, scientists know the genes Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 play an important role in the development of limbs in animals. The arrival of CRISPR now means that related genes can be edited in fish for the first time, which is what the researchers attempted in this experiment.

They discovered that in genetically altered zebrafish and mice, the same cellular and genetic material was found to be responsible for the small, flexible bones in fin rays, as well as in the wrists and digits of four-legged animals.

"When I first saw these results, you could have knocked me over with a feather," says Shubin.

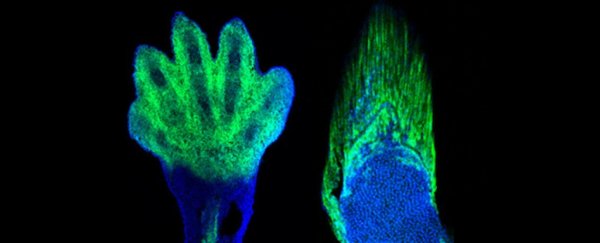

Two sets of experiments were run alongside each other. In the first, limb-building genes were deleted in zebrafish to analyse the effect on fin ray growth. In the second, the same genes were altered to glow under a CT scan as they developed. Comparable genetic changes were also made to groups of mice.

The researchers found that in both mice and zebrafish, the same genetic code appears to be telling embryonic cells to show up at the end of a limb, but uses different types of tissue along the way – cartilage-based (endochondral) bone in mice and other land creatures, and dermal bone in fish.

The findings offer a vital clue about the links between our own hands and the fins of deep sea creatures, and the researchers suggest that CRISPR could be used to find more evolutionary relationships in the future.

The findings are published in Nature.