Rates of gestational diabetes in the US increased unabated from 2016 to 2024, as revealed by a new study by Northwestern University researchers who drew on data from nearly 13 million first-time single-baby births.

Paired with earlier research from 2011-2019, the findings suggest gestational diabetes in the US has been on the incline for nearly 15 years.

"Gestational diabetes has been persistently increasing for more than 10 years, which means whatever we have been trying to do to address diabetes in pregnancy has not been working," says cardiologist Nilay Shah.

Related: A Distinct New Type of Diabetes Is Officially Recognized

Diabetes describes conditions that interfere with the body's ability to transport sugar from the blood into cells, a process mediated by the hormone insulin.

Chemicals produced by the placenta during pregnancy risk making the body's cells resistant to the hormone. Usually, the body compensates for this by producing more insulin.

Gestational diabetes can develop in cases where this compensation doesn't occur, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes developing in the future for both the parent and child.

The resulting high blood glucose levels can also turbo-charge growth in the developing foetus as more sugars and fats cross the placenta, potentially leading to a larger birth weight and difficulties during birth.

Treatment varies for each individual and their circumstances, but may include dietary changes, exercise, blood sugar monitoring, insulin injections, and close monitoring.

Shah and team hope their new research will help improve management and prevention strategies, especially among groups who are most affected.

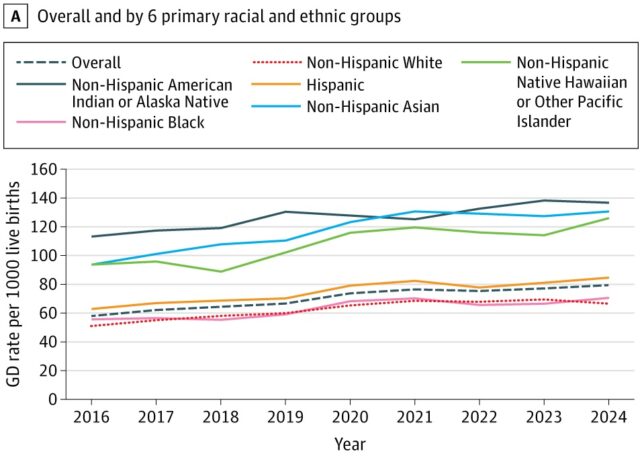

During the combined nine years from 2016 to 2024, gestational diabetes rates increased by a total of 36 percent. The researchers calculated this based on National Center for Health Statistics birth certificates for all first-time single infant births within the period. In the US, a diagnosis of gestational diabetes is usually marked on the birth certificate when treatment for glucose intolerance was required during pregnancy.

Breaking down the data by race and ethnicity revealed increases across all groups. However, rates in some demographics were much higher than others, with American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander mothers far more likely to be diagnosed with the condition.

In 2024, 137 out of every thousand American Indian/Alaska Native mothers giving birth had gestational diabetes; for Asian mothers, this rate was 131 for every thousand births; and 126 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander mothers had gestational diabetes for every thousand births.

"The reasons for the differences in gestational diabetes rates across individual groups are an important area for further research," Shah says.

Possible reasons include risk factor burden (when a certain group is more likely to be exposed to certain factors that increase the risk of disease), health behaviors and care access, social exposures, and discrimination in healthcare settings.

For instance, according to the previous 2011-2019 study, Hispanic/Latina individuals had a relatively higher body mass index and a lower educational attainment, both of which are risk factors for gestational diabetes.

However, Asian Indian individuals had the highest rates of gestational diabetes in that study, despite lower BMI levels and higher educational attainment.

"These data clearly show that we are not doing enough to support the health of the US population, especially young women before and during pregnancy," Shah says.

"Public health and policy interventions should focus on helping all people access high-quality care and have the time and means to maintain healthful behaviors."

The research is published in JAMA Internal Medicine.