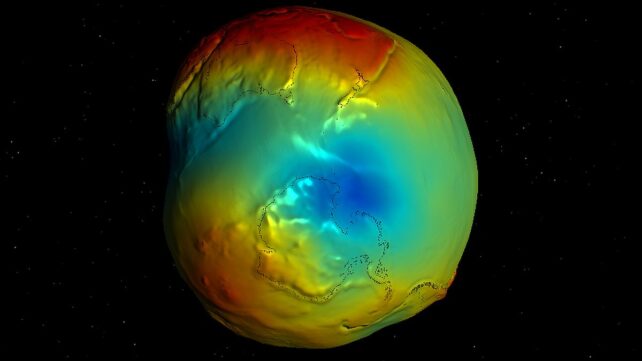

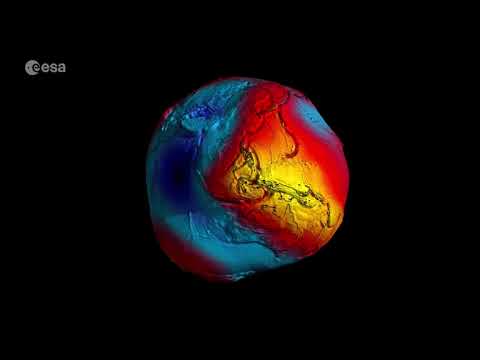

Although Earth is approximately spherical, its gravity field doesn't adhere to the same geometry. In visualizations, it more closely resembles a potato, with bumps and divots.

One of the strongest of these depressions – where the gravity field is weaker – lies under Antarctica. Now, new models of how the so-called Antarctic Geoid Low evolved over time have shown that it's only getting stronger, driven by the long, slow movement of rock deep below Earth's surface, like a giant shifting in its sleep.

"If we can better understand how Earth's interior shapes gravity and sea levels, we gain insight into factors that may matter for the growth and stability of large ice sheets," says geophysicist Alessandro Forte of the University of Florida.

Earth's geoid – the bumpy potato shape of the gravitational field – is uneven because gravity is linked to mass, and the mass distribution inside the planet is uneven, due to different rock compositions having different densities.

It's not a huge difference that you'd notice at the surface. Maps tend to exaggerate it so we can see what's going on; if you weighed yourself at a geoid low and a geoid high, the difference would be just a few grams.

Nevertheless, the geoid represents a window into processes deep inside Earth that we can't observe directly.

Forte and his colleague, geophysicist Petar Glišović of the Paris Institute of Earth Physics in France, generated a detailed map of the Antarctic Geoid Low using another window into Earth's interior: earthquakes. Seismic waves from earthquakes travel through the planet, changing speed and direction as they encounter materials with different compositions and densities.

"Imagine doing a CT scan of the whole Earth, but we don't have X-rays like we do in a medical office," Forte explains. "We have earthquakes. Earthquake waves provide the 'light' that illuminates the interior of the planet."

Using the earthquake data, the researchers constructed a 3D density model of Earth's mantle and extrapolated it into a new map of the entire planetary geoid. They compared this map with the gold-standard gravity data collected by satellites and found it to be a close match.

That was the easy part. The next step was to try to turn back the clock to assess how the geoid has evolved since the early Cenozoic, 70 million years ago.

Forte and Glišović fed their map into a physics-based model of Earth's mantle convection, rewinding Earth's interior geological activity to see how the geoid evolved over that timeframe.

Then, from their starting point, they let the model run forward to see if it could reproduce the geoid we see today.

They also checked whether their model reproduced real changes in Earth's rotational axis known as True Polar Wander. It arrived at the current geoid and matched the polar wander, suggesting it also provides an accurate representation of the geoid's evolution.

The results showed that the Antarctic Geoid Low is not a new development; a gravitational depression has been sitting near Antarctica for at least 70 million years. But it hasn't remained static. About 50 million years ago, its position and strength started to change dramatically – timing that matches a sharp bend in the polar wander.

According to the model, the anomaly formed as tectonic slabs subducted beneath Antarctica and sank deep into the mantle, altering the planet's gravity field at the surface. Meanwhile, a broad region of hot, buoyant material rose upward, becoming more influential over the past 40 million years and strengthening the geoid low.

Related: There's a Giant Gravity Hole In The Indian Ocean, And We May Finally Know Why

Interestingly, this may be linked to the glaciation of Antarctica, which began in earnest around 34 million years ago. It's only a speculative link, but here's the interesting thing about the geoid: it shapes sea level. So, as the geoid shifted downward around Antarctica, the local sea surface would have lowered with it – potentially influencing the growth of the ice sheet.

That's obviously a hypothesis that requires further testing. However, the work does show that different geodynamic processes, from mantle convection to the geoid to the motion of the poles, can all be connected and influence each other.

The gravity hole under Antarctica may be subtle, but it is a reminder that even the slowest processes deep inside Earth can leave a lasting impression on the world above.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.