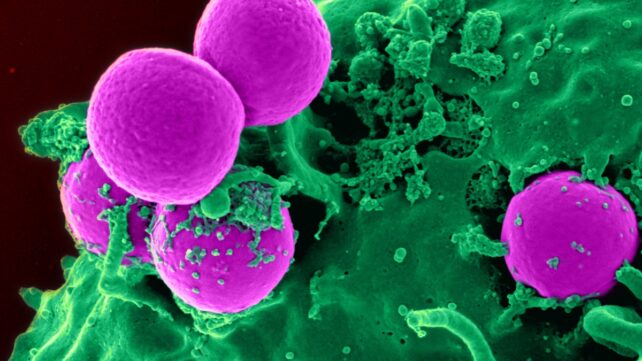

Dangerous bacteria and other disease-causing microbes are rapidly evolving ways to defy our best antibiotic medications, a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance. Humans are inadvertently contributing by overexposing pathogens to our limited defenses.

With drug-resistant bacteria already killing more than 1 million people a year, researchers are seeking clues about the future of these superbugs by examining the world's wastewater.

A new study by an international team of researchers has found that latent antimicrobial resistance is more common than we realised.

Related: Study Reveals 'Alarming' Rise of Superbugs in Newborn Babies

The scientists hunted for clues in wastewater from around the world, sifting through 1,240 sewage samples from 351 cities across 111 countries in search of the antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) that grant microbes protection against our life-saving medications.

Aside from known ARGs, the researchers used a process known as functional metagenomics to scour their samples for latent genes, or genetic variations that exist within an organism's DNA but are not actively expressed.

Latent genes can become active under certain circumstances, which means latent ARGs might play important roles in the poorly understood evolution of drug-resistant 'superbugs.'

The new study suggests latent ARGs are abundant nearly everywhere, forming a hidden global library of latent antimicrobial resistance. This latent resistance is apparently even more prevalent than the known resistance conferred by already active, or acquired, genes.

"The research shows that we have a latent reservoir of antimicrobial resistance that is far more widespread around the world than we had expected," says first author Hannah-Marie Martiny, a bioinformatician at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). This may be because selection and competition seem to play a larger role in the development of these resistance genes than dispersal, the researchers found.

One noteworthy takeaway from this discovery is the need for more proactive wastewater surveillance, says co-first author Patrick Munk, an associate professor with the DTU National Food Institute.

"To curb future antimicrobial resistance, we believe that routine surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in wastewater, in addition to including already acquired resistance genes, should also encompass latent resistance genes, in order to account for tomorrow's problems as well," Munk says.

Researchers often focus on ARGs that can be transferred among species of microbes, since these acquired ARGs already pose a threat to public health.

If we broaden our surveillance of sewage, however, we might learn valuable secrets from latent ARGs, possibly helping researchers demystify the origins of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) or map the ecology of the genes involved.

"By tracking both acquired and latent antimicrobial resistance genes, we can gain a broad overview of how they develop, change hosts, and spread in our environment, and thereby better target efforts against antimicrobial resistance," Martiny says.

"Wastewater is a practical and ethical way to monitor AMR," she adds, "because it aggregates waste from humans, animals, and the immediate surroundings."

Most of these genes may not endanger public health right now, the researchers note, but some of them probably will in the future.

"In general, I don't think we need to be too worried about most latent antimicrobial resistance genes, but I do believe that some of them will eventually cause problems, and we would like to know which ones," Martiny says.

That kind of knowledge could help us predict which microbes in the future might be vulnerable to which antimicrobial treatments.

"When new antibiotics are developed – a process that takes many years – bacteria may already have invented new 'scissors' capable of destroying them," Munk says.

"If we can study both types of genes over time," he adds, "we may be able to find out which of the latent genes become problematic resistance genes, how they arise, and how they spread across geography and bacteria, and in that way lessen the burden of antimicrobial resistance."

The study was published in Nature Communications.