An odd bird found in a Texas backyard is the offspring of two distantly related species, separated by 7 million years of evolution, whose ranges only recently began to overlap due to climate change, researchers report in a new study.

The bird is descended from a blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), which is native to the eastern and central United States, and a green jay (Cyanocorax luxuosus), which traditionally occurs in Central America, Mexico, and southern Texas.

"We think it's the first observed vertebrate that's hybridized as a result of two species both expanding their ranges due, at least in part, to climate change," says ecologist Brian Stokes of the University of Texas at Austin.

Related: Biologists Find Spectacular Bird That's Both Male And Female, Split Down The Middle

Vertebrate hybrids have occurred in the wild before, often due to human activity, such as the introduction of invasive species to new habitats, or due to one species' range expanding into another's, such as brown bears moving north and hybridizing with polar bears.

This hybrid jay, however, seems to be the first-known progeny from two distinct parent species whose ranges both expanded and converged due to changing weather patterns.

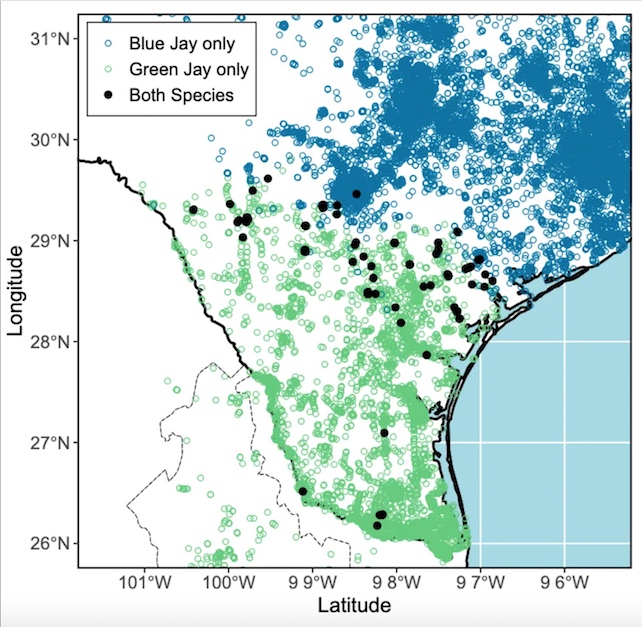

Green jays are vivid corvids mainly found in the tropics and subtropics, with a broad distribution stretching from Honduras to South Texas. Blue jays occupy a vast swath of eastern North America, but historically, their range didn't extend beyond eastern parts of Texas.

Until recently, the two jays rarely crossed paths.

Human activities have increasingly allowed both species to creep toward each other. Rising temperatures are expanding the tropical and subtropical climate zones, for example, helping green jays move into northerly regions that were once too cold for them.

At the same time, blue jays have been expanding both northward and westward since the mid-20th century, enabled by climate change as well as various land-use changes upon which they've managed to capitalize. This includes a westerly incursion across Texas.

The two species' expansions are converging around the city of San Antonio, Stokes and his colleagues note. Stokes regularly monitors online birding forums for interesting sightings in the region, which is how the blue-green jay – grue or bleen, perhaps – came to his attention.

A birder from a San Antonio suburb had posted a photo of an unusual bird in 2023, featuring a mainly blue body with a black face and white chest. Intrigued, Stokes got permission to visit the yard and try for a closer look.

"The first day, we tried to catch it, but it was really uncooperative," Stokes says. "But the second day, we got lucky."

The researchers snagged the jay in a mist net, whose fine nylon mesh makes it difficult for a flying bird to notice.

Before releasing the bird, Stokes collected a blood sample and banded its leg, so it could be identified if spotted again.

The jay was not seen again for a few years, but in June 2025, it abruptly reappeared in the very same backyard.

"I don't know what it was, but it was kind of like random happenstance," Stokes says. "If it had gone two houses down, probably it would have never been reported anywhere."

The bird is a male hybrid, the researchers report in the new study, descended from a blue-jay father and a green-jay mother.

This is not entirely unprecedented, as researchers in the 1970s deliberately bred the two species in captivity, yielding an offspring that looked similar to this new hybrid. The difference, of course, is that the two species are now evidently also hybridizing on their own in the wild.

"Hybridization is probably way more common in the natural world than researchers know about because there's just so much inability to report these things happening," Stokes says.

"And it's probably possible in a lot of species that we just don't see because they're physically separated from one another and so they don't get the chance to try to mate," he adds.

The study was published in Ecology and Evolution.