Scientists have calculated that 275 million tonnes of plastic waste was generated in 192 coastal countries in 2010 alone, with 4.8 to 12.7 million entering the world's oceans. And they say this figure could quadruple by 2025 if we keep going the way we are.

It sounds nuts, but despite common sense telling us that plastic in our oceans will likely be a huge problem for decades - and probably centuries - to come, we have surprisingly little data to help us understand exactly what we're up against. Since the 1970s, no rigorous estimates have existed regarding the amount and origin of plastic debris entering our marine environments. So a team, led by engineer Jenna R. Jambeck from the University of Georgia in the US, finally quantified how much of our plastic waste shifts from the land to the ocean on an annual basis, and the results, as expected, aren't pretty.

Publishing in the current edition of Science, the team reports that back in 1975, the estimated annual flow of all litter - not just plastic - that made it into the ocean was 5.8 million tonnes. And while the disposal of plastic waste from oceanic vessels has since been banned, this number continues to rise, thanks to global plastic resin production increasing at an alarming rate. In 2012, the researchers report, 288 million tonnes of plastic were produced, which marks a 620 percent increase since 1975.

This plastic ends up on our coastlines, in the Arctic sea ice, on the sea surface, and settles on the sea floor. It gets weathered down into tiny particles that are ingested by the very creatures we end up eating, and the particles are so small, we can't even detect them properly.

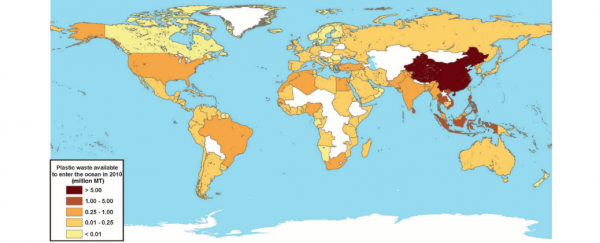

Jambeck and her team estimated the mass of land-based plastic waste that's entering the ocean by analysing worldwide data on the production, management, and disposal of solid waste in 192 coastal countries around the world, with populations living within 50 km of the coast. This included the mass of waste generated per capita annually, the percentage of which is plastic, and the percentage of this plastic waste that each country is mismanaging. The figures were then linked to the country's population density and economic status to figure out which countries were the worst offenders, which you can see in the infographic above.

They say the amount of land-based plastic making its way into our oceans is somewhere between 4.7 and 12.7 million tonnes, with 8 million being the best estimate. "That's enough to cover the world's entire coastline," Brad Plumer points out at Vox.

As you can see above, China is now responsible for around a quarter of the world's ocean-based plastic waste.

"Population size and the quality of waste management systems largely determine which countries contribute the greatest mass of uncaptured waste available to become plastic marine debris," the team reports. "Without waste management infrastructure improvements, the cumulative quantity of plastic waste available to enter the ocean from land is predicted to increase by an order of magnitude by 2025."

But where does this 8 million tonnes of plastic actually end up? That's a whole lot less clear. Researchers have so far identified five floating garbage patches in the world's oceans, inducing the Great Pacific garbage patch. The size of this monster accumulation is estimated to be between 700,000 square kilometres - about the size of Texas - and more than 15,000,000 square kilometres.

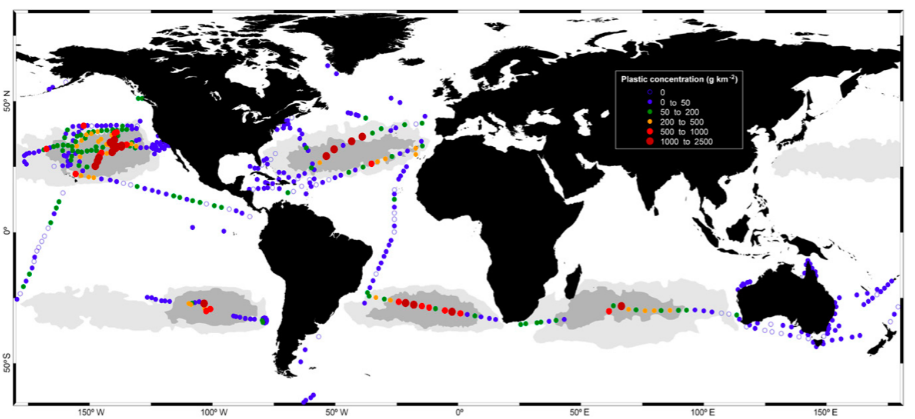

Last year, a separate team of researchers, led by biologist Andres Cózar from the Universidad de Cadiz in Spain, studied these gyres to find that they hold between 6,300 and 31,000 tonnes of plastic. They put this infographic together to show where the debris is ending up in the world's marine surface water:

Concentrations of plastic debris in the world's surface waters. Credit: Cozar et. al.

Concentrations of plastic debris in the world's surface waters. Credit: Cozar et. al.

But even having fond all this, we're still missing millions and millions of tonnes that we know is ending up in our oceans, we just haven't nailed down where. Plumer has put together a great run-down of the possible explanations over at Vox, which range from washing back to shore to being in pieces that are too tiny to detect, or eaten by sea life.

Even if you don't care about the environment, you probably care about what goes into you're eating, so this affects anyone who eats seafood, and there are a whole lot of us. And if we've learnt anything from Predator, it's that finding the enemy is the easy part. Strapping a bomb to the proverbial wrist of our missing ocean plastic will be the real challenge.

Source: Vox