Japanese people are, overall, pretty healthy, with one of the highest average lifespans in the world. But among high risk factors for death in Japan is hypertension, or high blood pressure.

Japan has the second-highest rate of chronic kidney disease in the world, with one in every eight people affected. Now researchers have determined that it may have something to do with the structure of their kidneys at birth.

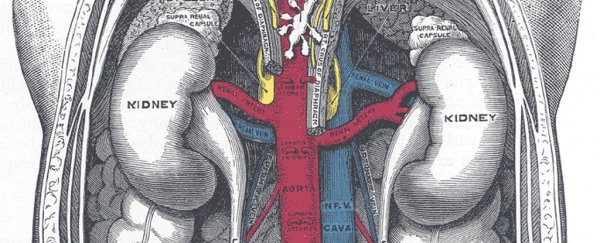

More specifically, the problem might lie with nephrons, the structural unit in the kidneys that's responsible for filtering.

According to a team from Monash University's Biomedicine Discovery Institute in Australia and the Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo, Japanese people have far fewer nephrons than average - and this has broader health implications.

The idea that a lower nephron count could be responsible for hypertension was first floated in the 1980s, said lead researcher John Bertram from Monash University, who has decades worth of experience in nephron research.

The link makes sense - the kidney determines the amount of both sodium and renin in the bloodstream. Sodium raises the blood pressure, and renin regulates it.

However, nephrons are very small, and hard to count, so this connection has historically been difficult to verify. Research relies heavily on nephron counts from autopsies.

Bertram's team studied 59 kidneys from 59 individual patients collected at autopsy, and, he said, found a clear correlation between nephron count and hypertension.

"This paper, the first such study in an Asian population, shows that Japanese with hypertension have significantly fewer nephrons than normotensive Japanese do - it's a clear-cut finding," Bertram said.

The research team found Japanese people without hypertension or kidney disease had 640,000 nephrons, compared to the European average of 900,000 to one million. This figure dropped to 392,000 if the person had hypertension and 268,000 if they had chronic kidney disease.

"In the present study, 9 Japanese hypertensive subjects with a mean age of 68 years had 37 percent fewer nephrons than 9 normotensive subjects with a mean age of 64 years," the researchers wrote in the paper.

Previous research led by Bertram has found a correlation between low nephron count and low birth weight. He has also conducted research that has found higher rates of low birthrate, low nephron counts, and higher rates of hypertension and kidney disease in African American and Australian Aboriginal populations.

Pre-term and low weight births have risen in Japan over the last three decades, and Go Kanzaki from Jikei University said the results have implications for the future.

"There is a trend towards Japanese women staying thin and small during pregnancy to try to look beautiful but their babies are more likely to be born smaller and with smaller kidneys and therefore less nephrons - the number of nephrons is set at birth," he said.

It's worth noting that while research supports this trend, the reasons for it may be slightly more serious than female vanity.

"Japan recommends stricter limiting of weight gain during pregnancy, compared to other developed countries," researchers wrote in a 2016 paper published in Scientific Reports.

"In this context, pregnant Japanese women are expected to weigh themselves at every perinatal check-up … Moreover, the majority of Japanese women believe that carrying a smaller baby would ensure a smooth delivery, which can lead them to avoid extra weight gain during their pregnancy."

But if a safe method of counting nephrons could be devised for living patients, it could also help predict high blood pressure and chronic kidney disease before they became a problem.

"Ultimately," Bertram said, "you would hope that health professionals will think more about low birth weight although the idea's not there yet."

The research has been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.