The Hubble space telescope has spent the past 30 years orbiting 547 km (340 miles) above Earth. The ageing satellite has had a couple of hiccups in the last few years, but it's not done taking incredible photos of our cosmic backyard yet.

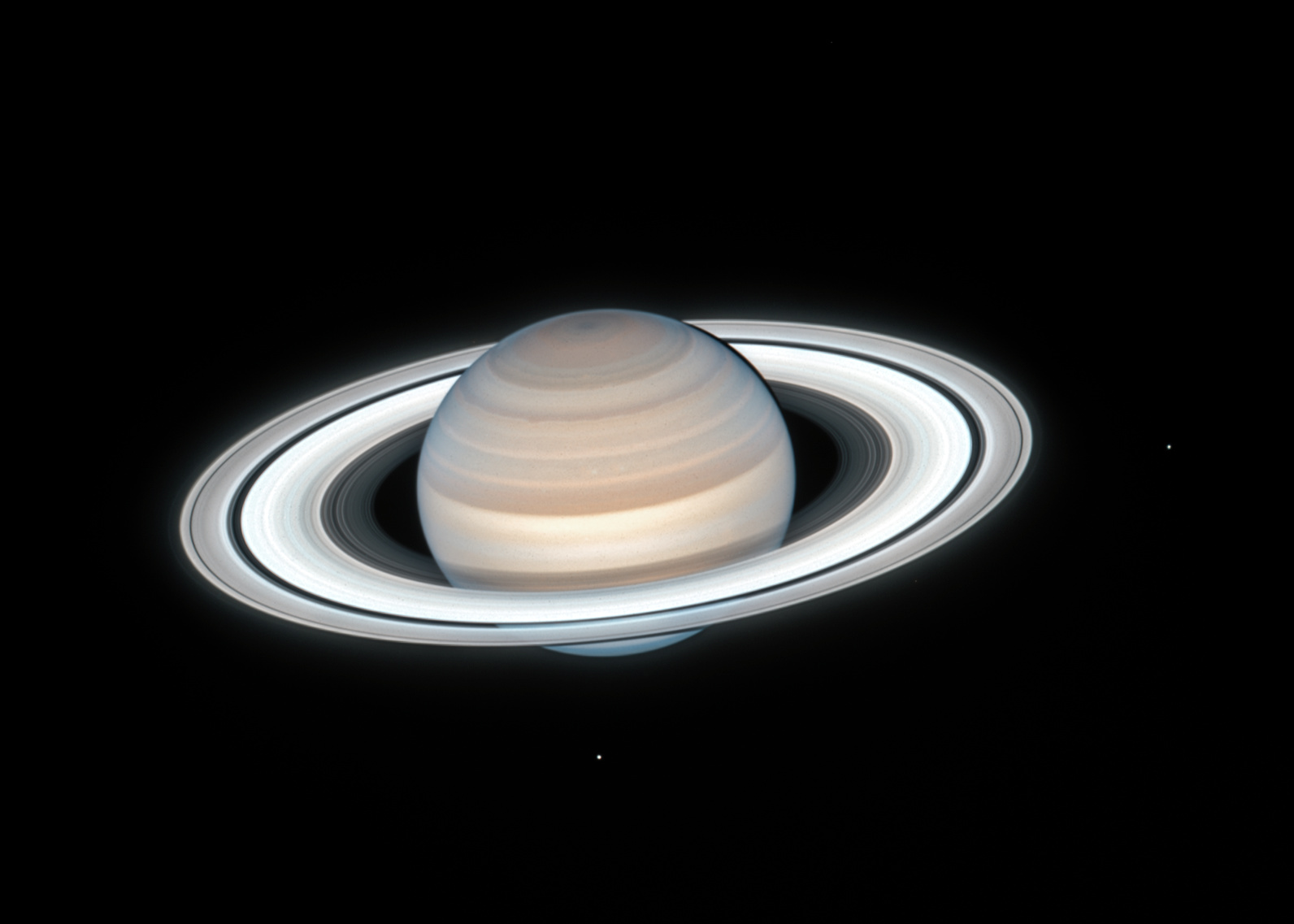

For example, earlier this month, Hubble flexed its Solar System chops, and took a crystal-clear image of Saturn from 1.35 billion kilometres (839 million miles) away – a planet which you can normally only see as a pinprick of light with the naked eye.

Right now, it's summer in Saturn's northern hemisphere, which, as we can see, means its top north half is tilted towards us (and the Sun).

But it's not quite summer as we imagine it. The gas giant gains most of its heat from its interior, rather than the Sun, and the average temperature is a chilly -178 degrees Celsius (-288 degrees F).

Not only is this image stunning, it helps scientists learn new details about the planet. For example, there's a slight red haze in the northern hemisphere.

NASA thinks this could be due to heat from sunlight changing the atmospheric circulation, or altering the photochemical haze on the planet. As you can see in the bottom of the picture, the south pole has a slightly blue hue.

"It's amazing that even over a few years, we're seeing seasonal changes on Saturn," said planetary scientist Amy Simon of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre.

(NASA/ESA/A. Simon, Goddard/M.H. Wong, UC Berkeley/OPAL Team)

(NASA/ESA/A. Simon, Goddard/M.H. Wong, UC Berkeley/OPAL Team)

In the picture you can also see two of Saturn's 82 moons: Mimas, the tiny dot on the right of the image, and Enceladus, the slightly larger dot at the bottom of the image.

Hubble has made more than 1.3 million observations since 1990 when it first launched, and most of those images are distant galaxies, nebulae, or stars – but occasionally it snaps a pic of a planet closer to home.

Saturn, for example, has had pictures taken every year as part of the Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) – with each photo looking slightly different.

These close-ups help scientists keep an eye on our Solar System without expensive and long-term missions to each of the planets.

That being said though, some questions need spacecraft for answers – like just how Saturn's incredible rings formed.

"NASA's Cassini spacecraft measurements of tiny grains raining into Saturn's atmosphere suggest the rings can only last for 300 million more years, which is one of the arguments for a young age of the ring system," said planetary scientist Michael Wong of the University of California, Berkeley.