A satellite that measures methane leaks from oil and gas companies is set to start circulating the Earth 15 times a day next month. Google plans to have the data mapped by the end of the year for the whole world to see.

The partnership between Google and the Environmental Defense Fund, which in March is expected to launch its satellite known as MethaneSAT, marks a new era of global climate accountability. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas estimated to be responsible for nearly a third of human-caused global warming.

Scientists say slashing methane emissions is one of the fastest ways to slow the climate crisis because methane has 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over a decade.

"Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record," Steve Hamburg, the EDF's chief scientist and the project lead for MethaneSAT, told reporters. "The need to protect the climate has never been more urgent, and cutting methane emissions from fossil-fuel operations and agriculture is really the fastest way that we can slow the warming right now."

Agriculture – particularly cow burps — gets a lot of the blame for the methane problem. The International Energy Agency has said farming is the largest source of methane emissions from human activities, but the energy sector is a close second.

Oil, gas, and coal operations are thought to account for 40 percent of global methane emissions from human activities. The IEA says focusing on the energy sector should be a priority, in part because reducing methane leaks is cost-effective. Leaking gas can be captured and sold, and the technology to do that is relatively cheap.

But methane has been difficult to track in near-real time. MethaneSAT is among a new generation of satellites designed to pinpoint sources of the gas almost anywhere in the world, while Google has the computing power and artificial-intelligence prowess to analyze vast amounts of data and map oil and gas infrastructure.

Historically, measuring methane leaks has involved expensive field studies with airplanes and handheld infrared cameras. That approach offers only a snapshot in time, and research took years to be published.

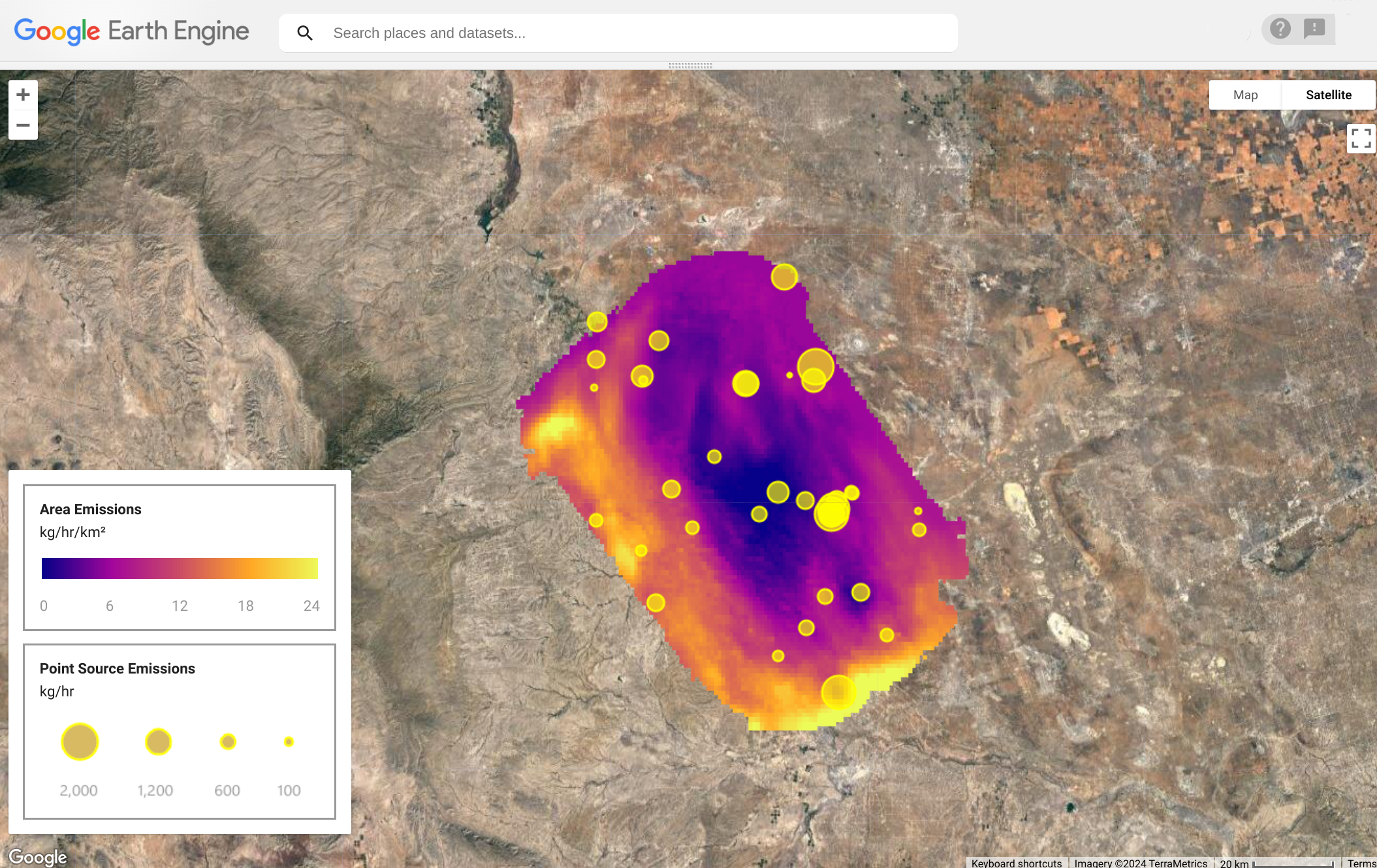

Yael Maguire, a vice president and general manager of sustainability at Google Geo – the team behind platforms such as Google Maps and Street View – said mapping oil and gas operations was similarly challenging. The locations of wellheads, industrial pumps, and storage tanks can change quickly, so a map needs to be updated regularly. A satellite can meet that demand.

Maguire said the same AI technology that Google used to detect trees, crosswalks, and intersections from satellite imagery would be applied to oil and gas infrastructure. The map would be overlaid with data from MethaneSAT to shed light on the type of machinery most susceptible to leaks.

"We think this information is incredibly valuable for energy companies, researchers, and the public sector to anticipate and mitigate methane emissions in components that are generally most susceptible," Maguire said.

Global methane pledges

The satellite launch comes as countries and oil and gas companies aim to drastically reduce methane emissions by 2030 to tackle the climate crisis.

During the UN climate summit in Dubai last year, companies accounting for 40 percent of global oil and gas production promised to nearly eliminate methane leaks from their own operations this decade. At least 155 countries have also signed the Global Methane Pledge, which calls for a 30 percent reduction in emissions. The pledge was launched in 2021, but since then, methane emissions have continued to rise.

To help change that trajectory, the US and Europe last year issued regulations cracking down on methane emissions from fossil-fuel infrastructure. The European Union's rules went a step further by targeting oil and gas imports.

Europe imports about 80 percent of its energy, including from the US. By 2027, those imports are expected to meet methane-emissions standards on par with Europe's.

Hamburg said Japan and South Korea, both of which rely on energy imports, were looking at similar laws.

"This means methane is becoming a competitive challenge for the industry, not just a regulatory one," he said. "Achieving real results means that the government, civil society, and industry need to know how much methane is coming from where, who is responsible for those emissions, and how those emissions are changing over time. We need the data on a global scale."

Maguire said Google planned to make the data available free for the public on Google Earth Engine later this year.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: