Imagine knowing in your 20s or 30s that you carry a gene that will cause your mind and body to slowly unravel.

Huntington's disease is inherited, relentless, and fatal, and there is no cure. Families live with the certainty of decline stretching across generations.

Now, a new treatment is being widely reported as a breakthrough.

Related: Breakthrough Gene Therapy Slows Huntington's Disease by 75%

Last week, gene therapy company uniQure announced that a one-time brain infusion appeared to slow the disease in a small clinical study.

If confirmed, this would not only be a landmark for Huntington's disease but potentially the first time a gene therapy has shown promise in any adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder.

But the results, which were announced in a press release, are early, unreviewed, and based on external comparisons. So, while these findings offer families hope after decades of failure, we need to remain cautious.

What is Huntington's disease?

Huntington's is a rare but devastating disease, affecting around five to ten people in 100,000 in Western countries. That means thousands in Australia and hundreds of thousands worldwide.

Symptoms usually start in mid-life. They include involuntary movements, depression, irritability, and progressive decline in thinking and memory. People lose the ability to work, manage money, live independently, and eventually care for themselves. Most die ten to 20 years after onset.

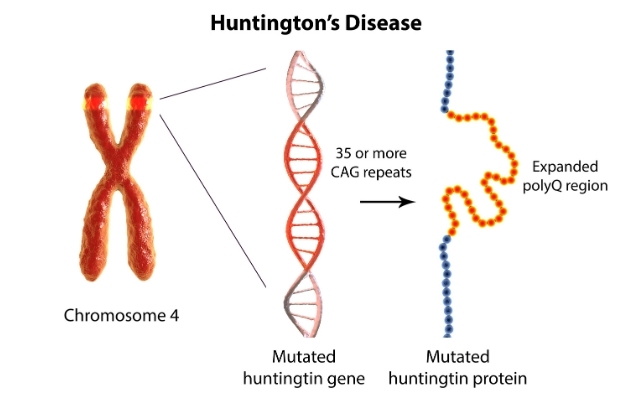

The disease is caused by an expanded stretch of certain DNA repeats (CAG) in the huntingtin gene. The number of repeats strongly influences when symptoms begin, with longer expansions usually linked to earlier onset.

Looking for a treatment

The gene that causes Huntington's disease was identified in 1993, 32 years ago. Soon afterwards, mouse studies showed that switching off the mutant huntingtin protein even after symptoms had begun could reverse signs and improve behaviour.

This suggested lowering the toxic protein might slow or even partly reverse the disease. Yet for three decades, every attempt to develop a therapy for people has failed to show convincing clinical benefit. Trials of huntingtin-lowering drugs and other approaches did not slow progression.

What is the new treatment?

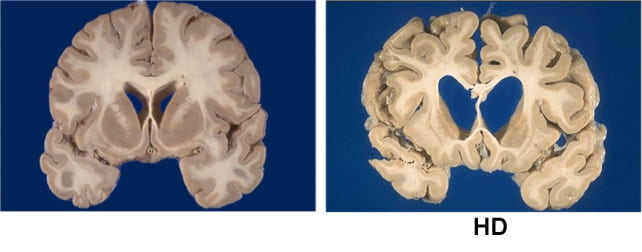

The one-time gene therapy, called AMT-130, involves brain surgery guided by MRI. Surgeons infuse an engineered virus directly into the caudate and putamen brain regions, which are heavily affected in Huntington's.

The virus carries a short genetic "microRNA" designed to reduce production of the affected huntingtin protein.

By delivering it straight into the brain, the treatment bypasses the blood–brain barrier. This natural wall usually prevents medicines from entering the central nervous system. That barrier helps explain why so many brain-targeted drugs have failed.

What did they find?

Some 29 patients received treatment, with 12 in each group (one low-dose, and one high-dose) followed for three years. According to uniQure, those given the higher dose declined much slower than expected.

The study compared how much participants' movement, thinking, and daily function declined, compared to a matched external group from a global Huntington's registry (meaning they weren't part of the study). The company claimed those given the higher dose had a 75% slowing in their decline.

On a functional scale focused on independence, the company reported a 60% slowing in decline for the higher dose group.

Other tests of movement and thinking also favoured treatment. Nerve-cell damage in spinal fluid was lower for study participants than would be expected for untreated patients.

Why should we be cautious?

These findings are an early snapshot of results reported by the company, not yet peer-reviewed. The study compared treated patients to an external matched control group, not people randomised to placebo at the same time. This design can introduce bias. The numbers are also small – only 12 patients at the three-year mark – so we can't draw solid conclusions.

The company reports the therapy was generally well tolerated, with no new serious adverse events related to the drug since late 2022. Most problems were related to the neurosurgical infusion itself, and resolved. But in a disease that already causes such severe symptoms, it is often hard to know what counts as a side effect.

The company uniQure has said it plans to seek regulatory approval in 2026 on the basis of this dataset.

Regulators will face difficult decisions: whether to allow access sooner before all the questions and uncertainties are addressed – based on the needs of a community with no effective options – and wait for further data while people are being treated, or to insist on larger trials that confirm results before approval.

What does it mean?

If upheld, these results represent the first convincing signs that a gene-targeted therapy can slow Huntington's disease. They may also be the first evidence of benefit from a gene therapy in any adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder. That would be a milestone after decades of failure.

But these results do not prove success. Only larger, longer, and fully peer-reviewed studies will show whether this treatment truly changes lives. Even if approved, a complex neurosurgical gene therapy may not be easily accessible to all patients.

The company has said the drug's price would be similar to other gene therapies – which can cost over A$3 million per patient – and will have the added cost of brain surgery.

The takeaway

For families who carry this gene, the hope is profound. But caution is just as important.

We may be witnessing the first credible step toward slowing an inherited adult-onset neurodegenerative disease, or just an early signal that may not hold up.

Ultimately, only time and rigorous science will show whether this treatment delivers the benefits so urgently needed.![]()

Bryce Vissel, Cojoint Professor, School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.