It's well established that nuclear fusion - the reaction that powers our Sun - could be the key to unlocking clean, limitless energy here on Earth.

But one of the biggest challenges of modern science is how to harness the fusion reaction so that it produces more energy than it consumes. And a new paper claims to have found a way to do just that.

Instead of looking at how to optimise common fusion reactor designs, such as tokamaks or stellerators, a group of physicists experimentally tested some novel reactor types.

They found that a strange-looking sphere design could be the key to achieving net-positive nuclear fusion because, surprisingly, it has the potential to generate more energy than it uses.

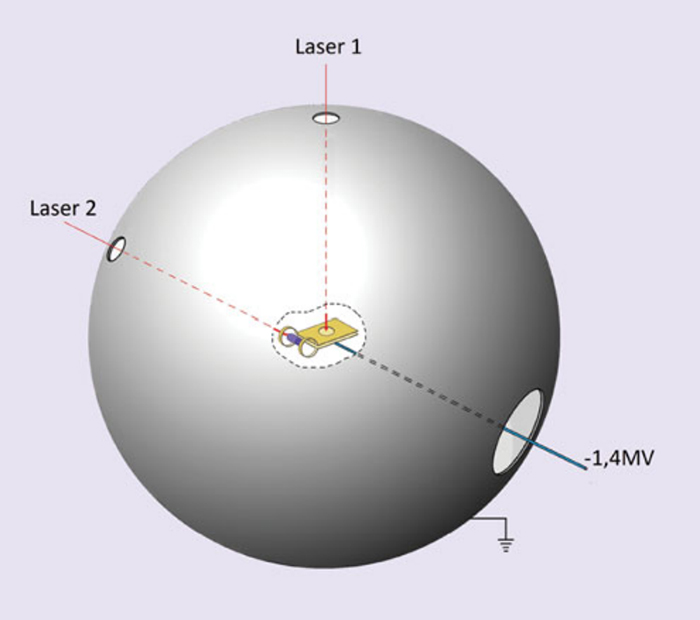

The key difference, aside from its shape, is that this nuclear sphere would fuse hydrogen and boron, rather than hydrogen isotopes such as deuterium and tritium. And it uses lasers to heat the core up to 200 times hotter than the centre of the Sun.

If the team's calculations are correct, the hydrogen-boron reactor device could be built and producing net-positive energy way before any of the reactors currently being tested reach completion.

Even better, the hydrogen-boron reaction produces no neutrons, and therefore doesn't create any radioactive waste as a byproduct.

"It is a most exciting thing to see these reactions confirmed in recent experiments and simulations," says lead researcher Heinrich Hora, from the University of New South Wales in Australia.

"I think this puts our approach ahead of all other fusion energy technologies.

Fusion reactions take the opposite approach to the nuclear fission reactions we rely on for our nuclear power today: instead of atoms being split, they're combined, or fused, together.

It's similar to the reactions that power the Sun, as lighter nuclei are fused to build heavier ones with the help of incredible temperatures and pressures.

As great as it sounds in theory, it's proving very difficult to harness in practice. The past two years have been record-breaking for fusion reactors around the world, with Germany switching on their much-hyped Wendelstein 7-X stellerator reactor.

But despite all our advances, we're not a whole lot closer to creating net-positive nuclear fusion. Put simply, that's because these machines just take so much energy to generate plasma.

In fact, Wendelstein 7-X isn't even intended to generate usable amounts of energy, ever. It's just a proof of concept.

But for years, Hora and her team have been working on alternative designs. And in this study, they tested them out experimentally as well as through simulations.

Their hydrogen-boron reactor works by triggering an "avalanche" fusion reaction from a laser beam packing a quadrillion watts of power in just a trillionth of a second.

You can see what it would look like below.

Diagram showing a hydrogen-boron reaction. (UNSW)

Diagram showing a hydrogen-boron reaction. (UNSW)

The latest tests put the hydrogen-boron approach ahead of other similar technologies, including deuterium-tritium fusion, which is being explored at the National Ignition Facility in the US (and also has the drawback of producing radioactive waste).

The team also put together a roadmap for further development of hydrogen-boron fusion.

The best news? If future research doesn't reveal any major engineering hurdles to this approach, the scientists reckon that a prototype reactor could be built within a decade.

While plenty of challenges remain in optimising the necessary reactions and keeping them stable enough to generate electricity, if this new fusion technique can be made to work, the benefits could be huge.

"The fuels and waste are safe, the reactor won't need a heat exchanger and steam turbine generator, and the lasers we need can be bought off the shelf," says Warren McKenzie, managing director of HB 11, which owns the patents to the new technology.

The research has been published in Laser and Particle Beams.