A modern male-centered view of archaeological remains has overlooked a possible matriarchal society in ancient Europe.

A lavish burial site from the Copper Age, unearthed in southwest Spain in 2008, is not the final resting place of a young male leader, as scientists once assumed.

As it turns out, the so-called 'Ivory Man' is actually an 'Ivory Lady'.

According to researchers at the University of Seville and the University of Vienna, the Ivory Lady's molars and incisors both contain the AMELX gene, which is involved in the production of tooth enamel and is located on the X chromosome.

The discovery suggests that women also held leadership positions in Europe's Copper Age society between 2900 and 2650 BCE.

In fact, societies in this region of the world may have been strongly matriarchal.

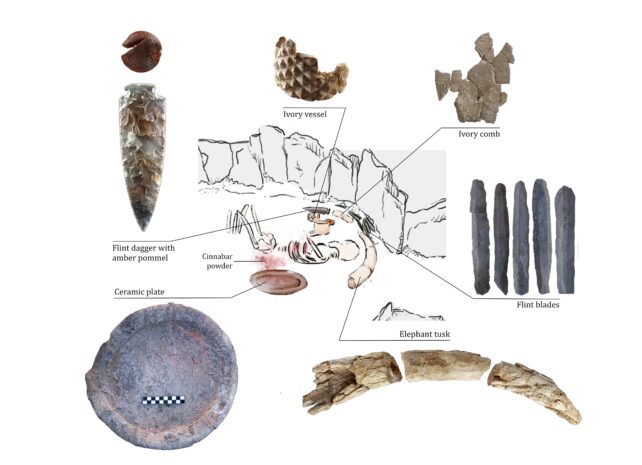

In the Ivory Lady's tomb in Valencia, researchers cataloged a diversity of precious objects, including a large ceramic plate containing remnants of wine and cannabis, a small copper awl, and various pieces of flint. She was even interred alongside a full African elephant tusk, weighing 1.8 kilograms (3.9 pounds), which would have been an especially valuable commodity then.

Several generations after her death, well-wishers seem to have left even more ivory objects near her grave, including a dazzling crystal dagger with an ivory handle.

"The quantity and quality of the artifact assemblage used as burial offering implies that this young person was the most socially prominent individual in the whole pre-Beaker Copper Age of the Iberian Peninsula," the authors of the study write.

Male burial sites at the time pale in comparison to hers.

The only other burial site with similar "pomp and wealth" contains mostly women and is only 100 meters (328 feet) away from the Ivory Lady. The megalithic tomb contains around 25 individuals, interred alongside gold blades, crystal arrowheads, and amber beads around 2875 to 2635 BCE.

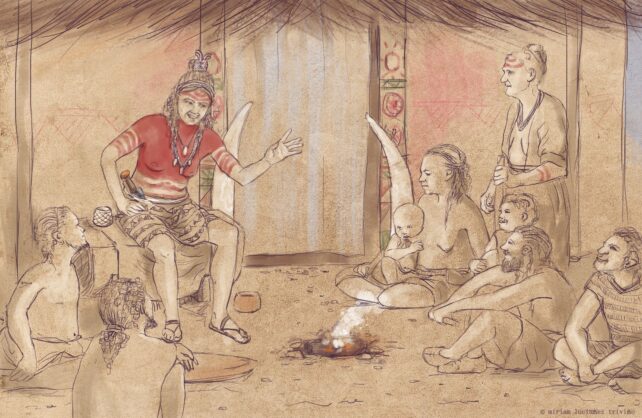

Based on how these bodies were laid to rest in a circle, these women were probably a group of religious specialists.

"Neither in Valencina nor in the whole of the Iberian Cooper Age has any other grave been found which remotely compares in material wealth and sophistication to these two graves," the team of researchers working on the Ivory Lady concludes.

Based on their findings, they theorize that between the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BC in Valencia, "women ostensibly enjoyed high-ranking positions not attained by men."

Because no infants in Valencia at this time were buried alongside lavish items, archaeologists suspect that social status in the ancient society was not inherited by birth. Instead, the Ivory Lady and other female leaders probably achieved their lofty positions through their charisma and achievements.

The Ivory Lady herself was probably no older than 25 years of age. Could she have been the young leader of a matriarchal society?

"The examples discussed here invite us to reconsider prevailing ideas about power, social complexity, and gender differences among early complex societies," the authors conclude.

"Moreover, it opens the door to reflect on the role that nineteenth-century discourse about wealth and gender play in modern interpretations, and the power of new scientific methods to challenge long-standing narratives of the past in the social sciences and the humanities."

The study was published in the Scientific Reports.