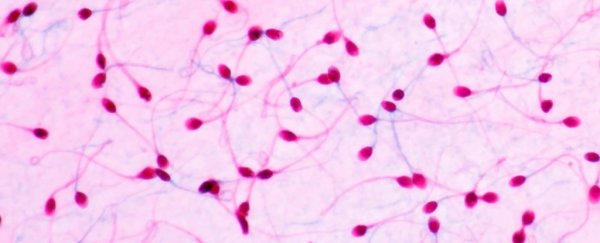

New research has shown that boys conceived through a type of IVF that targets male infertility have significantly lower sperm concentration and quality when compared to boys who were born naturally.

The findings are the result of the most detailed study to date on children conceived using this type of IVF procedure, and suggest that men who use IVF to conceive could inadvertently be passing their fertility problems on to their sons.

To figure this out, researchers from Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium examined the first group of boys in the world to be conceived using an IVF procedure known as intracytoplasmic sperm injections (ICSI).

Unlike the most commonly used IVF procedures today, which involve mixing many sperm cells in a petri dish with an egg until fertilisation occurs, ICSI involves injecting a single male sperm cell directly into an egg to achieve fertilisation.

The procedure was first developed in the 1990s to help men who were having trouble conceiving naturally, and has since become the most successful form of IVF to combat male infertility in the UK, and is used in nearly half of all IVF treatments nationally.

These days, ICSI is used to address a range of reproductive challenges, but the first babies born using the technique had one thing in common – their fathers had all been diagnosed with fertility problems. That means these boys offer a unique opportunity to see if fertility issues can be passed down to the next generation.

To figure this out, the Belgian team analysed sperm samples of 54 men who had been conceived in the first rounds of ICSI - between 1992 and 1996 - and compared them to 57 male controls who had been conceived naturally. The men were all aged between 18 and 22 years old, and were all single.

The researchers adjusted for factors that could affect sperm quality, such as age, BMI, and how long they'd gone without sex before the test.

Compared to the controls, they found that the ICSI men were three times more likely to have sperm concentrations that were lower than normal (over 15 million sperm per millilitre is considered normal).

The ICSI men were also four times more likely to have a sperm count below 39 million, which is the cut-off that doctors think increases a man's chance of conceiving – anything below that and it could indicate future fertility problems, as seen on the graph below:

Mikael Häggström, Wikimedia

Mikael Häggström, Wikimedia

On top of all that, the men who were conceived naturally on average had over double the amount of 'swimming' sperm - known as the median motile sperm count - which means their sperm would be more likely to reach and fertilise an egg when naturally conceiving.

To be clear, the researchers are not suggesting that this type of IVF procedure is causing fertility problems, or is somehow increasing the risk of the boys being born with low sperm quality of concentration. But the researchers say the results could indicate a link between a father's fertility problems and their son's.

The team says this is one of the first peer-reviewed studies to show clear evidence of fertility problems being passed down from father to son.

"These first results from the oldest group of ICSI-conceived adults worldwide indicate that a degree of 'sub-fertility' has, indeed, been passed on to sons of fathers who underwent ICSI because of impaired semen characteristics," said one of the team, André Van Steirteghem, who is also one of the pioneers of ICSI.

"Before ICSI was carried out, prospective parents were informed that it may well be that their sons may have impaired sperm and semen like their fathers," he added.

That said, the results aren't quite as clear-cut as we might expect, because it's very difficult to say for sure that these fertility problems were the direct result of genetics.

When the researchers compared sperm concentration and total motile sperm count between the fathers and sons, the values did not correlate - but the overall trend did.

The sperm counts were also based on one-off measurements, which could have been influenced by a number of other factors – such as whether the men had drunk a lot the night before.

As Van Steirteghem himself admits, they've so far only found a link here, but further research is needed to find a firm biological or genetic association between low fertility in fathers and sons.

"The study shows that semen characteristics of ICSI fathers do not predict semen values in their son," he says. "It is well established that genetic factors play a role in male infertility, but many other factors may also interfere. Furthermore, correlation is not the same thing as causation."

Interestingly, despite their lower sperm quality, the men in the study hadn't reported any fertility issues themselves, so it's not clear whether their low sperm counts would actually go on to affect their likelihood of having children.

Further research is now needed to figure out exactly what's going on, and to try and pinpoint genetic evidence of male infertility being passed down through generations.

"This finding supports concerns that the infertility of a father could be passed on to male offspring, but does not prove it," the UK National Health Service reports.

The research was published in Human Reproduction.