A NASA mission to observe the activity of the solar wind has returned its first images of giant coronal mass ejections (CMEs) billowing out from the Sun.

Images from the Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere (PUNCH) were presented at the 246th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, showing these giant events on an unprecedented scale.

"I promise you you have never seen anything quite like this," heliophysicist and PUNCH principal investigator Craig DeForest of the Southwest Research Institute said in his presentation.

CMEs are huge expulsions of billions of tons of solar plasma and magnetic fields that are blasted out from the Sun, a massive release of energy and solar particles that occurs when the Sun's magnetic field lines tangle, snap, and reconnect. They often, but don't always, occur with solar flares.

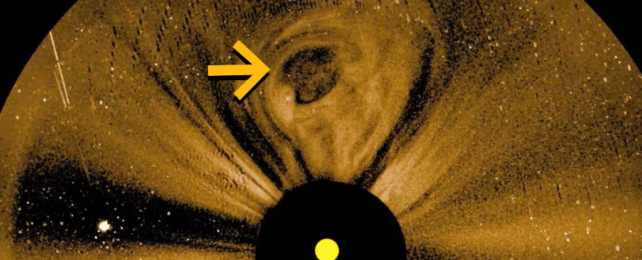

A halo CME is what we call it when the CME blasts right in the direction of Earth. From our perspective, the expanding ejecta looks to surround the Sun like a halo, before barreling through the Solar System at tremendous speed.

"That halo CME is something you have never seen before. I'd like to call your attention to the white circle near the center of the field of view here. That circle represents the LASCO field of view; that is the largest coronagraph currently used to forecast space weather.

"You've seen halo CME movies before, if you've paid attention to the science press. But you have never seen one 30 to 40 degrees from the Sun … you're seeing something that is literally washing across the entire sky of the inner Solar System as it comes toward the Earth."

In this case, they were able to track a CME as it blasted through the Solar System at 4 million miles an hour until about two hours before it collided with Earth's magnetic field. These events often produce the aurora that light up Earth's polar skies, but can also interrupt communications and damage satellites, so scientists are keen to develop better space weather tracking and prediction tools.

PUNCH is just beginning its planned two-year mission to record solar events in 3D, in an attempt to better understand space weather. The four probes aren't quite yet in their final positions, but the team here on Earth is testing the instruments and taking observations.

"These are preliminary data. They look good now, but they are going to look fabulous once we are done with calibration later this summer," DeForest said. "This is the first of many, I'm sure, and the best is still to come."