Even a boneless, gelatinous sack lacking a dedicated anus and brain needs its beauty sleep, a new study by researchers from Bar-Ilan University in Israel finds.

Jellyfish sleep a third of every day away, just like we do, despite their outlandishly different physiology.

This suggests the origin of sleep is extremely ancient, as human ancestors diverged from the jellyfish phylum (Cnidaria) as far back as around a billion years ago.

Related: These Sea Creatures Don't Need a Brain to Learn, According to a New Study

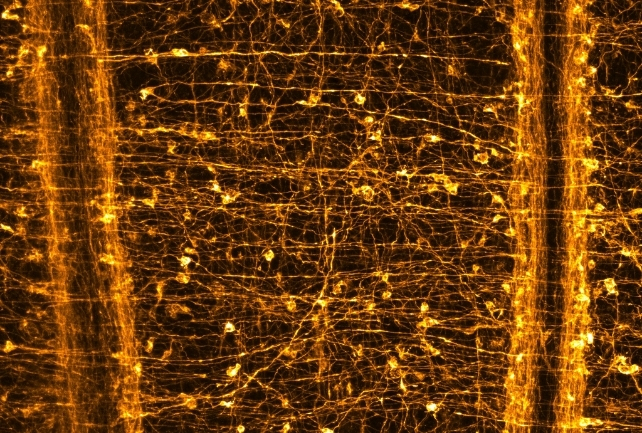

Cnidaria lack a centralized brain. Instead, they have neural networks lining the length of their bodies. Despite this simple neural arrangement, these water drifters have been observed sleeping, just like animals with nervous systems happen to do.

The period of immobility and decreased arousal comes with risks, though.

"The evolution of sleep came with major fitness compromises, such as

reduced awareness of the environment and vulnerability to predation," explain chronobiologist Raphaël Aguillon and colleagues in their paper.

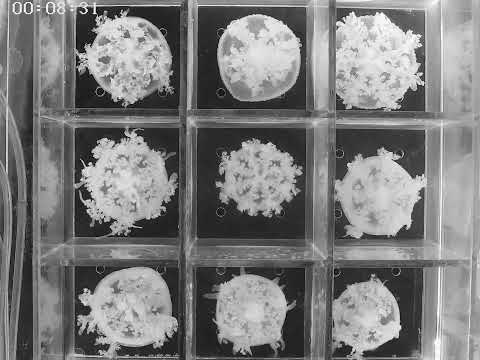

Yet, jellyfish tend to sleep through the night like humans, and even nap around midday. Meanwhile, their close relative, the sea anemone, takes the night shift, sleeping during daylight hours. So there must be a powerful benefit to sleeping that counteracts the risks.

Specimens of upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda) and starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) suffered an increase in neuronal DNA damage when deprived of sleep, something the researchers observed under both laboratory and natural conditions.

What's more, if their external environment caused increased neuronal DNA damage, both Cnidaria slept more. The findings suggest that sleep may have evolved as a way to protect cells from damage.

When treated with melatonin, the animals slept more, and DNA damage was subsequently reduced. The researchers suspect that Cnidarians use a melatonin system like ours to synchronize their sleep cycles to daylight cycles.

"Sleep deprivation, ultraviolet radiation, and mutagens increased neuronal DNA damage and sleep pressure," the team writes in their paper.

"Spontaneous and induced sleep facilitated genome stability."

So even simple neural systems require rest to reduce the inevitable DNA damage that accompanies wakefulness.

"The balance between DNA damage and repair is insufficient during wakefulness, and sleep provides a consolidated period for efficient cellular maintenance in individual neurons," suggest Aguillon, Harduf, and their team.

"These results suggest that DNA damage and cellular stress in simple nerve nets may have driven the evolution of sleep."

This research was published in Nature Communications.