Galileo Galilei had one of the brightest scientific minds we've ever seen.

Amongst his many achievements was helping to finally cement the idea that Earth orbits the Sun, rather than the other way around – but a newly discovered letter reveals how he toned down his views to avoid angering the church.

The note was found by science historian Salvatore Ricciardo, from the University of Bergamo in Italy, as he browsed through a catalogue stored in the Royal Society Library in London in the UK.

Originally written more than 400 years ago in 1613, the letter puts to rest a long-standing mystery among historians: whether those close to the church doctored Galileo's writings to make his views sound more extreme, and to get him into more trouble with the Catholic Church and the Inquisition.

"I thought, 'I can't believe that I have discovered the letter that virtually all Galileo scholars thought to be hopelessly lost,'" Ricciardo told Nature. "It seemed even more incredible because the letter was not in an obscure library, but in the Royal Society library."

The letter represents the first written record we have of Galileo's heliocentric views, put down in pen and ink for his friend Benedetto Castelli, a mathematician at the University of Pisa in Italy.

But two versions of this famous text exist today – one with quite inflammatory language and one that takes a more diplomatic approach to upturning centuries of scientific thought. The question is: which version came first?

At the time, the church was very clear on how Earth was sitting at the centre of the Universe, as God intended; not, as astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus suggested in 1543, orbiting around the Sun.

In his writing Galileo agreed with Copernicus, based on his own observations. He also suggested parts of the Bible shouldn't be taken too literally in regard to our physical place in the cosmos.

Galileo always insisted that the copy of his letter that was used to stir up conflict with the Vatican – copied and passed on by a Dominican friar called Niccolò Lorini – had been doctored to make his views seem more extreme than they actually were.

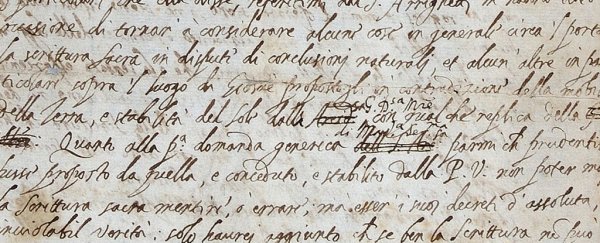

This newly found letter appears to contradict that: it shows both the original wording (first sent to Castelli) and Galileo's edits on top, watering down his vocabulary. Galileo apparently had this edited version copied and passed on to the Vatican in his defence.

In other words, Galileo did tone down his wording, but not before the original copy had spread beyond his control. The original was actually the one passed on by Lorini, according to this latest discovery.

In one sentence Galileo describes certain ideas in the Bible as "false if one goes by the literal meaning of the words" – in the edit, "false" has been replaced with "look different from the truth".

Elsewhere, a description of the Bible "concealing" certain facts was changed to "veiling", another example of how the rewrite was intended to be less inflammatory.

Handwriting analysis suggests the edits are indeed in Galileo's own hand, while the document's date and "GG" signature are further proof of its authenticity. It's possible that an incorrect date attached to the letter meant it stayed hidden for so long.

Despite his hurried self-editing, Galileo was ordered to renounce his heliocentric views, something he pointedly refused to do by publishing Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1632.

That led to a condemnation for heresy in 1633 and a prison sentence, later commuted to house arrest that lasted for the final nine years of his life. Galileo wasn't officially pardoned by the Vatican until 1992.

Now the researchers are working to try and find out how the letter got to the Royal Society Library – quite an unusual home for this type of document.

"Strange as it might seem, it has gone unnoticed for centuries, as if it were transparent," says Franco Giudice from the University of Bergamo in Italy, who is Ricciardo's postdoc supervisor and helped him verify the find.

"Galileo's letter to Castelli is one of the first secular manifestos about the freedom of science – it's the first time in my life I have been involved in such a thrilling discovery."

An analysis of the letter is scheduled to be published in Notes and Records.