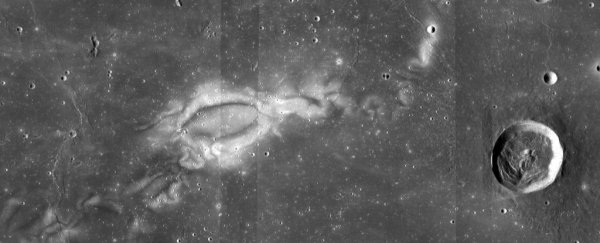

If you look at the Moon through a telescope, you might see something curious on the surface. The bright, undulating patterns are called lunar swirls, and their origins have been an ongoing mystery - not least because they are associated with powerful, localised magnetic fields.

Now scientists think they may have solved a part of the puzzle. The surface patterns, their research has found, are caused by subterranean lava tubes.

The lunar swirls and their strange magnetism has been known for decades. The Apollo 15 and 16 missions helped map sources of magnetism on the Moon - which has no global magnetic field - and these were linked to the swirls in a paper published back in 1979.

It's certainly a strange mystery to crack.

At higher altitudes, the swirls are less pronounced and intricate than the ones at a lower altitude, and while every swirl has a magnetic field, there are magnetic fields on the Moon that don't have swirls.

On top of that, while the swirls are not new, they have the spectral characteristics of new formations; that is, they are less weathered than the surrounding regolith.

The mechanisms at play are unknown, but one possibility is that the magnetic fields around the swirls deflect particles blown in from the solar wind, causing them to weather more slowly.

"But the cause of those magnetic fields, and thus of the swirls themselves, had long been a mystery," said planetary scientist Sonia Tikoo of Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

"To solve it, we had to find out what kind of geological feature could produce these magnetic fields - and why their magnetism is so powerful."

Using computer modelling, the team discovered that each swirl has to be close to or above a narrow, magnetic object not far from the lunar surface. And lava tubes, or vertical lava dikes, which are the result of long-ceased lunar volcanic activity, fit that description nicely.

These formations are the result of basalt lava flows, which also left large, dark basalt plains all over the lunar surface between 3 and 4 billion years ago.

And this could explain how those underground formations became magnetised. Because something happens when Moon rock is heated to temperatures around 875 Kelvin (600 degrees Celsius, or 1,112 Fahrenheit) in the presence of a magnetic field, in an anoxic environment.

It becomes highly magnetised. That's because the heat causes some of the minerals to break down, releasing iron. In the presence of a strong enough magnetic field, that iron will then become magnetised in the same direction of the field.

It doesn't happen here on Earth, because of the oxygen; and it wouldn't happen on the Moon if there were lava flows now, because it lost its magnetic field long ago.

But according to research published by Tikoo and colleagues last year, the lunar magnetic field persisted much longer than previously thought - up to 2 billion years longer. So its presence could have coincided with the lava flows.

And bada boom, there you have it: magnetic lava tubes.

"No one had thought about this reaction in terms of explaining these unusually strong magnetic features on the Moon," Tikoo said. "This was the final piece in the puzzle of understanding the magnetism that underlies these lunar swirls."

Of course, the best way to learn more would be to actually go there and study one of the swirls directly. Add that to the agenda for the next lunar mission.

The research has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.