The shredded carcasses of microscopic marine algae could play an important role in the formation of clouds over the world's oceans, a new study has found.

We all know clouds form as microscopic water droplets in the air condense on the surface of microscopic particles. These particles can be soluble – such as where salt crystals soak up the water – or insoluble, like dust, collecting water on their external surface.

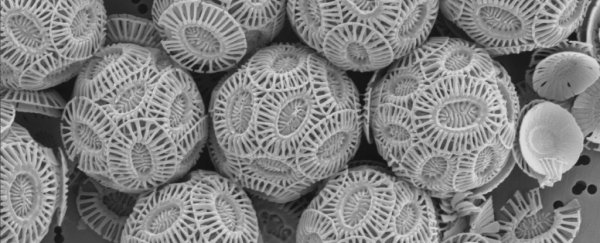

A single-celled species of alga, or phytoplankton, called Emiliania huxleyi could be responsible for far more of these cloud seeding particles than previously thought. Blown apart from the inside by a common virus, their hard shells form insoluble particles on which water droplets condense in the atmosphere.

This phytoplankton is ubiquitous throughout the world's oceans. It's so common, you've probably seen pictures of its familiar calcium carbonate shell made up of tiny plates called coccoliths.

When the conditions are right, the alga blooms, its vast numbers colouring the oceans bright shades of turquoise in spite of the microscopic size of the individual organisms.

When they – and other shelled phytoplankton – die, most of their coccoliths end up as part of the sediment on the ocean floor.

But not all. Traces of E. huxleyi coccoliths have been found in sea spray, borne aloft by breaking waves, or bubbles in the water.

Sea spray aerosols play an important role in regulating Earth's climate, and the presence of phytoplankton has been found to increase the number of cloud droplets over the ocean.

But the role these algae play in cloud formation, if any, hasn't been entirely clear.

To try to figure it out, a team of researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, grabbed a whole bunch of E. huxleyi and infected half of them with a virus that commonly infects them in nature. The other half were kept virus-free as a control.

At the beginning of the experiment, each millilitre of water contained around 20 million empty coccoliths. After 5 days, this number had more than tripled for the infected algae, compared to the control.

Then they used bubbles to mimic the natural churning of the ocean that would create sea spray. There was 10 times more coccolith material in the air above the infected algae than above the control group.

But there's more. Because the coccoliths are so small and light, they stay airborne for a long time – they fall "25 times slower compared with sea salt particles with the same dimension," the researchers wrote.

This means in conditions where heavier particles might fall, the coccolith fragments don't, leaving them to concentrate in the air – and perhaps play a significant role in cloud formation.

On the other hand, they may do the opposite.

Living E. huxleyi, along with other marine microorganisms, produces a gas called dimethyl sulfide, which helps drive cloud formation. It's possible that fragments of calcium carbonate in the air react with the dimethyl sulfide and destroy it, reducing rather than increasing cloud propagation.

The next step to try and find out which of these scenarios is the case is to observe a bloom in action.

The team's research has been published in the journal iScience.