Vultures are not known for their museum conservation skills, but perhaps that ought to change.

Scientists have discovered an unlikely record of human history deep within layers of bone debris left by generations of bearded vultures and their bone-crunching babies, carefully preserved by the birds across the centuries.

There are only 309 breeding pairs of bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) remaining in Europe. But back in the 19th century, they inhabited hollows in cliff faces across the continent, including the Iberian Peninsula.

Related: Shift in India's Vulture Population Linked to Half a Million Human Deaths

All that remains of these now-extinct lineages in southern Spain are their nest sites, or 'eyries', some of which have sat unattended for 130 years.

Cliff-front property is hard to come by, so many raptors keep intergenerational nest sites 'in the family' across decades and even centuries.

The cliff caves favored by bearded vultures are particularly valuable. The sheltered, cooler microclimate of the caves provides ideal conditions for keeping accumulated bone remains fresh as chicks learn to munch away at them.

But it's not just their location that vultures prize: within this prime real estate, families of vultures hoard layers of nesting material, collected from their surrounds across the years.

The caves do such a good job of preserving the nesting material that scientists have recognized treasures of equal importance to our own species among the layers – and an impressively well-preserved record of local flora and fauna, too.

Ecologist Antoni Margalida from Spain's Institute for Game and Wildlife Research regularly visits nests maintained by the surviving bearded vultures, and has often noticed pieces of cloth, string, and other human-made materials placed across the bed to help insulate developing eggs.

This led him to suspect that vultures may have been collecting the flotsam and jetsam of our own species for quite a long time. He led a team to visit 12 abandoned bearded vulture nests in southern Spain and comb through these once-cherished family archives, layer by layer.

"Thanks to the solidity of bearded vulture nest structures and their locations in the western Mediterranean… they have acted as natural museums, conserving historical material in good condition," Margalida and team report.

The nests mainly comprised the bones of hoofed animals, providing a detailed record of the vultures' meals – and, by proxy, the animals that have inhabited the area – since medieval times.

"This basic historical data and that collected on feeding habits and nest-site selection provide quality information on the habitat characteristics and food species' selection of this species several centuries ago," the team explains.

Intermingled with the layers of bones were fragments of eggshells left behind by generations of vulture broods. Females only lay one or two eggs each year, so these fragments may allow for toxicology studies that contribute to conservation efforts by providing evidence of historic pesticide loads.

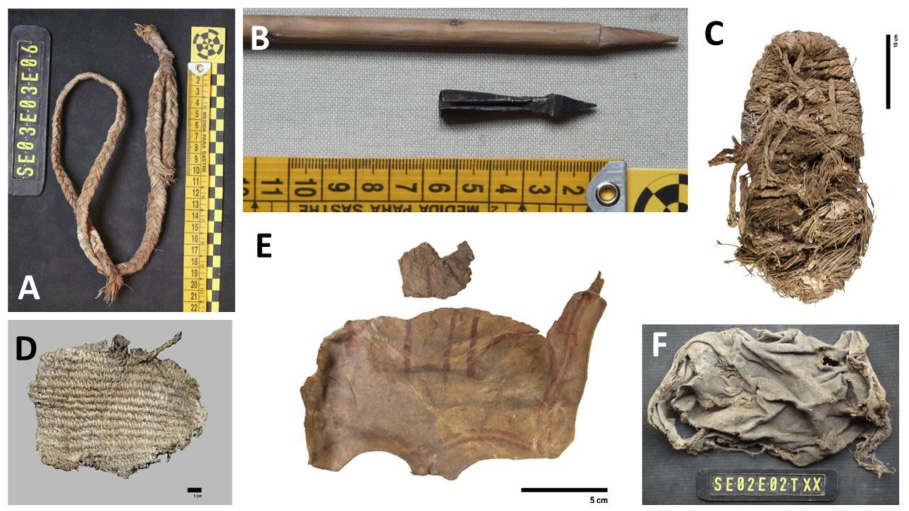

But the most exciting and unusual discoveries were of human origin: several ancient sandals, made from a variety of grasses and twigs – the oldest of which, a complete sandal made from esparto grass cord, was made 674 years ago in the late 14th century.

Along with a 650-year-old decorated piece of sheep leather found in the same nest, carbon isotopes confirmed that vultures established this particular nest five centuries earlier than another nearby.

The team also found a 151-year-old basket fragment; a crossbow bolt and its wooden lance; part of a slingshot made from braided esparto grass; and a range of other evidence of historical culture.

"All of these remains attest to the use of plant fibers in the Mediterranean region of the Iberian Peninsula to make a wide variety of artifacts from the Epipaleolithic period, around 12,000 years ago," the team writes.

"Bearded vultures as accumulators of bone and human artifacts in northern Iberian caves have provided insights into the prehistoric human groups who also lived there… thus, the bearded vulture could be regarded as a bioindicator of exceptional value for long-term ecosystem monitoring and interdisciplinary research."

Vultures melt bones with their gnarly stomach acid, clean up our environment, protect us from disease, and preserve our history along with their own. It's about time we showed them some respect.

This research was published in Ecology.