Scientists have hijacked the herpes virus and turned it into a cancer-busting ally.

A decade after the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first virus-based cancer therapy, another potentially life-saving treatment is on the horizon.

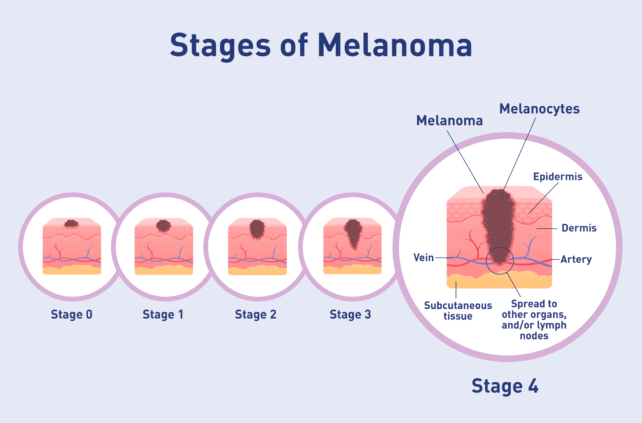

A genetically modified herpes simplex virus, called RP1, has now been shown to destroy advanced melanoma tumors, even when they exist deep in the body, according to a phase 1/2 clinical trial.

The trial involved injecting RP1 into melanoma tumors on or just below the surface of the skin, or deeper in the body like in the lungs or liver. In patients who responded positively to the treatment, even tumors not directly injected with the medicine began to shrink.

Related: Plant Virus Fights Cancers in Mice With 'Widespread Effectiveness'

"This result suggests that RP1 is effective in targeting cancer throughout the entire body and not just the injected tumor, which expands the potential effectiveness of the drug because some tumors may be more difficult or impossible to reach," says medical oncologist Gino Kim In from the University of Southern California.

The findings are not yet peer reviewed, but they were recently presented at the 2025 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting.

Intrigued by initial results, the FDA granted priority review to the RP1 therapy earlier this year, as long as it was in combination with the immune therapy nivolumab (brand name Opdivo).

Together, this drug duo seems to deliver a double punch to melanoma.

Of the 140 patients enrolled in the recent phase 1/2 clinical trial, roughly a third responded positively to the RP1 and nivolumab injections.

At first, patients were given a combined therapy every two weeks. But after eight cycles, the patients continued with just nivolumab for up to two years.

Among patients who responded well, about 80 to 90 percent of their tumors shrank by more than 30 percent.

The safety and efficacy of the herpes-based drug was considered similar for both the surface and deep injection sites. Although a version of the herpes virus is used as a carrier, it does not cause herpes in the patients.

"These findings are very encouraging because melanoma is the fifth most common cancer for adults, and about half of all advanced melanoma cases cannot be managed with currently available immunotherapy treatments," says In.

"The survival rate of untreatable advanced melanoma is only a few years, so this new therapy offers hope to patients who may have run out of options to fight the cancer."

To date, the FDA has approved just one virus-based cancer therapy – brand name Imlygic – and it can only be applied to advanced melanoma if the tumor exists on the skin or in the lymph nodes.

The newest engineered version of HSV-1 therapy could get crucial medicine deeper into the body.

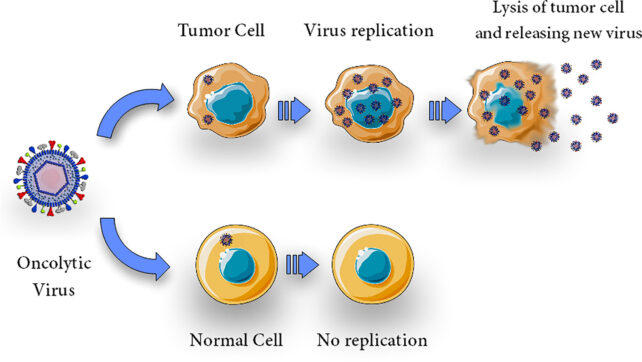

The drug research is being sponsored by a different biotech company, called Replimune Group, Inc., which is investing in oncolytic virus therapy – a clever technique that some think could change cancer treatment for good.

After all, viruses evolved to invade our cells. And while this might often be considered a bad thing, researchers investigating oncolytic virus therapy have turned that skill into a blessing. They have designed common viruses, like the herpes simplex virus, to avoid healthy cells and directly destroy cancer cells by causing them to burst.

Upon breaking apart, the cell is thought to release a bunch of immune substances, called antigens, that trigger the broader immune system into attack mode.

For cancers, like melanoma or brain tumors, which are protected by an immunosuppressive environment, oncolytic viruses could prove particularly useful as therapies.

Earlier this year, the FDA set a target action date for its review of RP1 and nivolumab to 22 July 2025.

If the therapy proves up to snuff, it could be available to some patients with treatment-resistant advanced melanoma very soon.

"I believe that oncolytic viruses will open up an important new approach to fighting cancer in some patients in the near future," says In.

A phase 3 trial with more than 400 participants is now underway.

The trial findings were presented at the 2025 ASCO Annual Meeting.