The ocean is vast, and deep, and dark, and inhospitable to us feeble land-dwelling creatures. There's much that remains unknown or poorly understood in its roiling, seething belly.

Technology is changing that.

For over a century, mariners have reported an eerily beautiful phenomenon they called the "milky sea" - enormous patches of glowing water that sometimes persist for several nights in a row. It wasn't until 2005 that this phenomenon was finally confirmed - in the form of photographs taken from a satellite in low-Earth orbit.

Now scientists have used nearly a decade's worth of satellite data to reveal the phenomenon in detail. Although much remains to be discovered, we've made some important steps towards understanding the largest known form of bioluminescence on Earth.

In his 1872 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Jules Verne wrote "It is called a milk sea .. a large extent of white wavelets often to be seen on the coasts of Amboyna .. the whiteness which surprises you is caused only by the presence of myriads of infusoria, a sort of luminous little worm".

The worm was conjecture on Verne's part, but milky seas are otherwise real. Patches of this phenomenon can be larger than 100,000 square kilometers (around 39,000 square miles), and have been reported a great deal in the last century or so: 235 sightings were cataloged between 1915 and 1993, which suggests an occurrence rate of at least thrice per year.

However, only once has a research vessel managed to sail through one, in 1985 in the Arabian Sea.

The water they collected contained, among other organisms, a bioluminescent marine bacterium called Vibrio harveyi; the researchers aboard the vessel concluded this was likely the source of the glow, but some features remained unexplained. In addition, their conclusions are yet to be verified.

The problems with verification are several. Milky seas occur in remote locations, primarily; and they are unpredictable, which means getting a research vessel in position prior to the appearance of one is nigh impossible. Now, using satellite imaging, a team of scientists led by marine biologist Steven Miller of Colorado State University hopes to fill in the gaps.

The NOAA's Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 are two weather satellites equipped with a variety of sensors, including an instrument called the Day/Night Band. This sensor is designed to capture low-light emission sources, under a variety of illumination conditions.

This means it's uniquely able to see faintly glowing patches of sea that other instruments might not. Sure enough, when Miller and his colleagues examined the Day/Night Band data for three commonly reported milky sea locations between 2012 and 2021, they found 12 instances of the phenomenon.

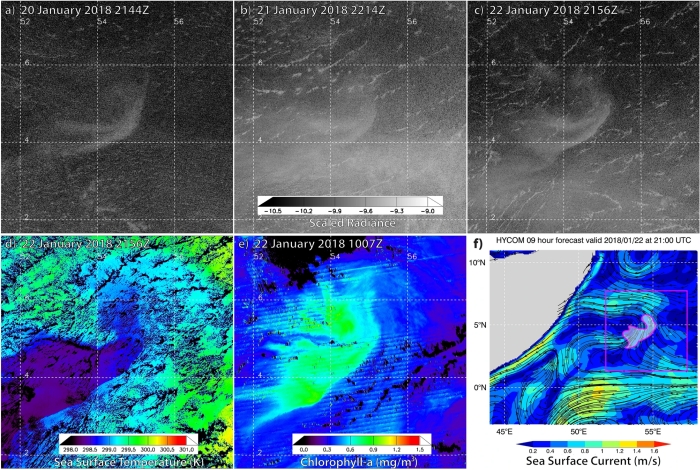

A three-night sequence from 2018 showing a milky sea in the Somali Sea. (Miller et al., Sci. Rep., 2021)

A three-night sequence from 2018 showing a milky sea in the Somali Sea. (Miller et al., Sci. Rep., 2021)

The Day/Night Band continues to amaze me with its ability to reveal light features of the night," Miller said. "Like Captain Ahab of Moby-Dick, the pursuit of these bioluminescent milky seas has been my personal 'white whale' of sorts for many years."

The glow has long been known to be a strange one. Unlike bioluminescent algae, which discharge flashes of light in a warning signal in response to being disturbed and often appear in tumbling waves and turbulent ship wakes, milky seas glow wide and steady. We don't know how they form, or why, or how the glow is composed and structured.

The team's data revealed that milky seas seem to resonate with the monsoons in the northwest Indian Ocean, which produces cool upwellings of nutrient-rich water, but no such monsoonal association was apparent in the Maritime Continent region.

This means that some other process could be providing nutrient upwellings when the milky seas appear there.

They also found that the bioluminescence remained stable and steady in choppy waters, which would not occur if the glow was confined to a surface slick. This suggests a well-mixed layer of water that contains the glowing organisms.

Physically sampling milky seas will, of course, help solve the mystery once and for all. The team hopes that their satellite data will show us the way to find them more easily.

"Milky seas are simply marvelous expressions of our biosphere whose significance in nature we have not yet fathomed," Miller said.

"Their very being spins an unlikely and compelling tale that ties the surface to the skies, the microscopic to the global scales, and the human experience and technology across the ages; from merchant ships of the 18th century to spaceships of the modern day. The Day/Night Band has lit yet another pathway to scientific discovery."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.