A mysterious and rapid rise in Legionnaires' disease, a severe bacterial lung infection, has been linked to cleaner air, in a US study of trends in sulfur dioxide pollution.

Puzzled by the lengthy global upsurge in Legionnaires' disease, an atypical form of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria, researchers at two US universities and the New York State Department of Health investigated possible environmental factors that could explain the trend in their neck of the woods.

Over the last two decades, the incidence of Legionnaires' disease in the US has increased nine-fold, from around 1,100 cases reported in 2000 to nearly 10,000 in 2018. Europe and parts of Canada have reported similar increases, with cases up five- to seven-fold.

While major outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease dating back to 1976 have been traced to air conditioners, commercial ventilation systems, and cooling towers – which use fans to dissipate heat from factories – in the vast majority of sporadic cases, no main source is known.

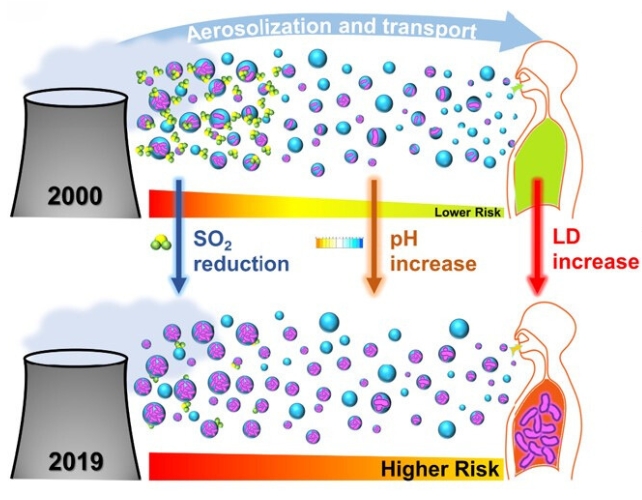

Airflow systems and cooling towers, if contaminated, spread Legionella bacteria over considerable distances by dispersing water vapor; the bacteria cling to airborne water droplets that people inhale. However, this could vary depending on environmental conditions.

"Understanding how changing environmental conditions influence Legionella proliferation is critical to mitigating this important public health risk," says atmospheric scientist Fangqun Yu of the University of Albany in New York, who co-led the study.

The researchers focused on New York state, after identifying it as the number one state for Legionnaires' disease in an analysis of cases reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 1992 and 2019.

However, none of the environmental factors the team initially studied – relative humidity, temperature, precipitation, and UV radiation – explained the long-term trend in Legionnaires' disease.

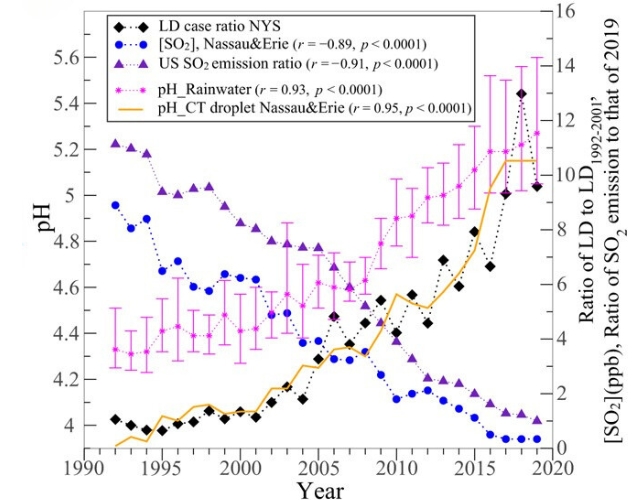

Looking further, they noticed that levels of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the air had decreased over the last two decades at a similar rate to the increases in Legionnaires' disease.

Using a model of water-based chemistry, they showed how atmospheric SO2 can be absorbed into water droplets, and converted into sulfuric acid, making the droplets more acidic and less hospitable to Legionella bacteria.

Conversely, the model showed decreases in SO2 levels recorded at two air quality monitoring sites in New York state over two decades would have made water droplets less acidic by at least a factor of ten.

Less acidic water vapor might allow Legionella bacteria to survive their airborne journey and infect whoever inhales them.

In fact, in a secondary analysis, the researchers found a one-week lag between decreased SO2 concentrations and rises in cases of Legionnaires' disease, which is about the incubation time from exposure to symptom onset.

By mapping their locations, they also identified a striking link between cases of Legionnaires' disease and their proximity to cooling towers in New York state.

This association doesn't prove cause and effect, and multiple factors could be contributing to the rise in Legionnaires' disease, which the researchers plan to investigate in future studies.

Communities located up to 7.3 kilometers (4.5 miles) from a cooling tower had a significantly higher risk of hospitalizations for Legionnaires' disease. This range has been increasing over the last 20 years as SO2 levels decreased, possibly extending the survival of Legionella in the air.

It highlights the importance of protecting vulnerable populations living near industrial or densely populated areas – firstly from air pollution, and secondly from this newfound risk of Legionnaires' disease that comes with clearer skies.

The researchers stress that reducing pollution is undoubtedly good for people and the environment; it's now a matter of using these findings to help inform strategies to limit Legionella exposure while maintaining good air quality and its many benefits.

The study has been published in PNAS Nexus.