The dawn of the Bronze Age was a tumultuous time for many human societies, as the social order of the preceding Copper Age fell apart. Yet little is known about this pivotal period in human history, including why exactly it happened or how people handled it.

In a new study, researchers take a closer look at this transformative era through the lens of Murayghat, an ancient archaeological site located near the city of Madaba in what is now Jordan.

The Copper (or Chalcolithic) Age had seen sedentary farming communities proliferate around the Levant in the Middle East, along with key advances like copper mining and smelting. Around 5,500 years ago, however, many of these communities seem to have experienced some kind of upheaval, either shrinking or abandoning their settlements.

Related: A 3,000-Year-Old Workshop May Have Revealed The Origins of The Iron Age

Previous research suggests the culture may have collapsed due to a mix of climate change and social disruption. The Chalcolithic was reportedly humid, with trees growing in the now treeless Negev desert, and its culmination coincided with a regional shift toward a drier climate.

Emerging in this context, Murayghat stands out from the area's earlier residential communities. It seems more like a place for ceremonial assemblies, says archaeologist and study author Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen.

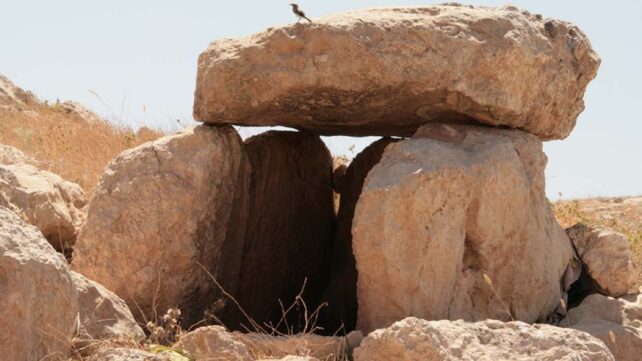

"Instead of the large domestic settlements with smaller shrines established during the Chalcolithic, our excavations at Early Bronze Age Murayghat show clusters of dolmens, standing stones, and large megalithic structures that point to ritual gatherings and communal burials rather than living quarters," Kerner says.

Dolmens, also known as portal tombs, are megalithic burial chambers typically consisting of two large vertical stones supporting a horizontal capstone. Kerner and her colleagues documented the remains of more than 95 dolmens at Murayghat dating to the Early Bronze Age, describing more than 70 of them in detail.

Although none of the dolmens appear to contain any remains, their resemblance to better-preserved dolmen fields in the region suggests a ceremonial purpose.

In addition to this high density of dolmens, the site's central hilltop is home to stone enclosures and carved bedrock that suggest ceremonial rather than residential use, Kerner reports. There is also little evidence of certain domestic amenities, such as hearths.

The architecture is a diverse mix of styles, which would be unusual for a residential site of this era. Yet it could be explained by different groups of people traveling to Murayghat and bringing their own traditions with them, Kerner points out.

The layout of the site and prominence of the dolmens support this interpretation, as do many of the artifacts found there. Pottery discovered at the site includes large communal bowls, for example, along with other items associated with rituals and feasting.

While a drying climate may have reshuffled the sociopolitical landscape of the late Chalcolithic Levant, it did not force people out of the area entirely. Some places evidently did suffer steep declines or even depopulation, but people also found ways to persevere.

"People had to find mechanisms to deal with a situation in which the traditional values and patterns of behaviour no longer worked," Kerner writes. "Thus, new ways to organize life (and death) had to be found, and found within a society with weak hierarchical structures, still dealing with a major disruption to everyday patterns of life."

Details about those adaptations remain elusive today, and after all these thousands of years, we may never truly understand what was going on at Murayghat in the Early Bronze Age.

It's worth trying to learn what we can, however, to illuminate how ancient people dealt with such dramatic turmoil, especially given the relative abundance of clues preserved at Murayghat.

"Murayghat gives us, we believe, fascinating new insights into how early societies coped with disruption by building monuments, redefining social roles, and creating new forms of community," Kerner says.

The study was published in Levant: The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant.