Here's some science trivia for you: unlike the inner retina in most animals (including us), birds' inner retinas function without oxygen. And now, researchers led by a team from Aarhus University in Denmark have figured out how.

In the retinas of almost all vertebrates, the oxygen required to convert glucose into sufficient amounts of energy for cells to function is delivered courtesy of red blood cells.

Not so with birds: there are no blood vessels in the retina, so oxygen can only arrive by diffusion through the surface, making the inner retina anoxic (without oxygen).

Cells can squeeze energy from glucose without oxygen, though the efficiency of the process is poor, and quickly generates a toxic build-up of waste.

Luckily, birds have evolved a solution in the form of a plumbing system that bird anatomists have debated the purpose of for centuries.

Related: We May Finally Understand Why Birds Burst Into Song at Dawn

"Our study reveals an impressive anoxia tolerance in the inner bird retina," write the researchers in their published paper.

"Our findings are interesting, as neural tissues of warm-blooded animals are generally considered to be highly vulnerable in anoxia, rapidly leading to cellular dysfunction."

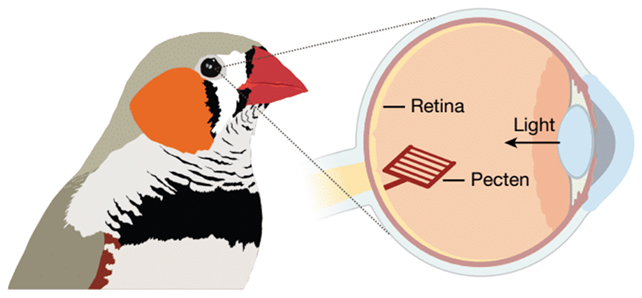

Crucial to tolerance is the pecten oculi, a part of the bird's eye discovered in the late 17th century. This structure, which sits next to the retina, is packed with blood vessels – but before now, it wasn't clear exactly how it worked.

Through some careful monitoring of the eyes of live zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata), including an analysis of oxygen levels, nutrient transport, and gene activity, the researchers confirmed that the inner retina uses no oxygen at all.

Instead, the retinal cells rely on a process called anaerobic glycolysis, where small amounts of energy are produced from glucose using an alternative set of reactions that don't require oxygen. Unfortunately, the process also creates lactic acid, which can damage tissue in high enough concentrations.

This brings us back to the pecten oculi: it does the job of transporting high volumes of glucose while removing the lactic acid before it harms retinal cells.

Part of the reason bird eyes may have evolved this feature is to reduce the need for vision-impairing blood vessels, or perhaps allow birds to migrate at high altitudes where oxygen is at a premium.

For instance, short-toed snake eagles (Circaetus gallicus) have retinas more than four times thicker than the limit for oxygen diffusion in mammal retinas, meaning a very large portion of the organ goes without oxygen. This may be a benefit to these birds, which soar 500 meters (more than 1500 feet) above ground for long periods of time.

"Establishing the function of this enigmatic structure in the birds' eye is super cool," says biologist Coen Elemans, from the University of Southern Denmark.

"This pecten allows a snake eagle the incredible acuity of vision to spot a tiny still lizard from great heights, but also may have had a crucial role in allowing birds to migrate. That is wild!"

The discovery could inform related research into cells surviving anoxic conditions. Knowing the tricks that bird eyes use might eventually inform treatments for strokes, for example, which is another scenario where nerve cells are starved of oxygen.

Now that scientists have a much clearer idea of what the pecten oculi is and what it's doing, future research can take a more detailed look at how crucial the glucose supply to the eye affects retinal performance. It certainly requires a lot of glucose to work properly: around 2.5 times the amount that bird brains take up, the study reports.

The research paper has actually been eight years in the making and involved contributions from experts in numerous different scientific fields, resulting in another important insight into how bird evolution has played out across millions of years.

"This study is really a tour de force and a beautiful piece of work that combines the expertise and hard work from many people," says Elemans.

The research has been published in Nature.