For most of us, this would be a nightmare.

Imagine being curled up inside a 90 centimeter (36 inch) fabric sphere with a small window and a small air tank while dangling from the Canadarm.

As your tiny sphere shifts, you'd see Earth out your tiny window, then the Space Shuttle, damaged by some accident or other that caused you to need rescuing, then Earth again. Panic would set in pretty quickly.

But that's where Space Shuttle astronauts in an emergency could've found themselves if NASA's Personal Rescue Enclosure (PRE) had been put into practice.

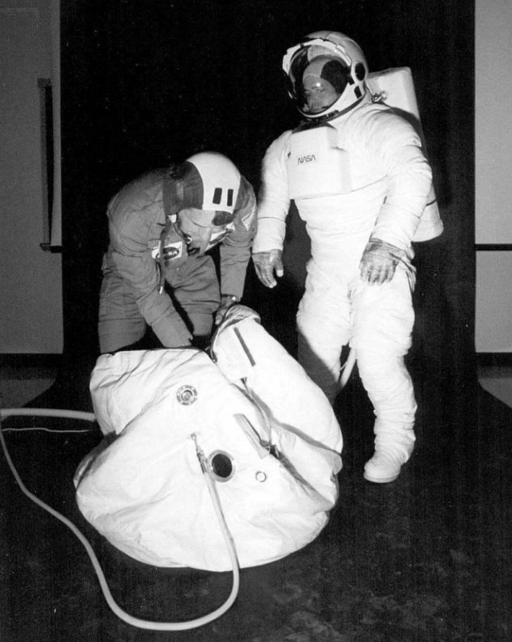

NASA developed the PRE simultaneously with the Space Shuttle Program. It's also called a rescue ball, and it was meant to transport a single astronaut from a damaged shuttle to a rescue shuttle. NASA produced a prototype, but it never went on any missions.

"If a shuttle orbiter should become disabled, the commander and payload specialist will get inside of a personal rescue enclosure; the pilot and mission specialist will don their spacesuits."

From NASA Facts: Space Shuttle

The PRE was only 0.33 cubic meters or 12 cubic feet. It was made of three layers of fabric: urethane, Kevlar, and an outer thermal layer. It had a small Lexan window and zippers for entry and exit. A single astronaut could fit inside, and it held a carbon dioxide scrubber/oxygen supply that would last one hour.

If this unit seems humorous to you, in the same vein as the "hide under your desk during a nuclear attack" school emergency drills, who can blame you?

The PRE was designed for a scenario where there were not enough spacesuits for everyone. Prior to the Challenger disaster, space shuttle crews didn't wear space suits. In the event of an accident, and if there was enough time to launch a rescue shuttle, the PRE system would be employed.

The PRE would be tethered to the Space Shuttle until the airlock depressurized, then a suited astronaut from the rescue shuttle would transport the PRE and the astronaut inside to the rescue shuttle.

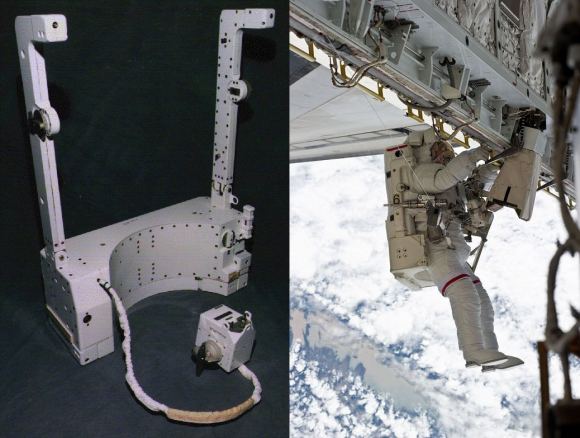

It could also be moved with the Canadarm or moved along a line connecting the two shuttles like a shirt on a clothesline. NASA planned to move an entire crew from a damaged shuttle to a rescue shuttle in this way.

NASA, as usual, was keen to share what they were working on with the wider public. The PRE was no exception.

In a 1979 booklet titled NASA Facts, they spoke with confidence about the upcoming Space Shuttle program, and how it "… will turn formidable and costly space missions into routine, economical operations generating maximum benefits for people everywhere." In that booklet, they showed the PRE and explained its relevance.

It's always interesting to look back to a time when the Shuttle Program hadn't actually started yet. Some of the hopefulness about the program came true, and people around the world probably felt hopeful, too. It's the kind of thing that gives you hope for humanity. But it's slightly amusing to see the PRE being presented in the same breath.

"If a shuttle orbiter should become disabled," the 1979 booklet said, "the commander and payload specialist will get inside of a personal rescue enclosure; the pilot and mission specialist will don their spacesuits."

In the lead-up to the Shuttle Program, the popular press covered the program extensively. The PRE even made it into Popular Mechanics, 'twixt competing cigarette ads, and ads for wood-paneled station wagons.

In the end, the PRE was abandoned. Common sense prevailed, and every person riding on the Space Shuttles was given a space suit.

In retrospect, the PRE seems more like a brutal hazing ritual than emergency preparation. The thing zipped up on the outside only, the window was tiny, and the poor person being rescued was entirely at the mercy of another astronaut. You can picture frat boys zipping pledges into it and pouring Pabst Blue Ribbon in through the air hose port. But we shouldn't be too hard on our predecessors.

The type of space flight the shuttles would engage in was unknown at the time, and the Shuttle Program changed everything. If there were some missteps along the way, so what? Nobody was harmed. You don't get where NASA is without trying ideas, testing them, then abandoning ones that, well, deserve to be abandoned.

Astronaut safety is paramount for NASA, and they've developed much better technologies to protect astronauts.

All astronauts working outside the ISS now wear the Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue (SAFER) system. It's a jetpack that allows astronauts to return to the ISS if their tether fails or they become separated from the Canadarm 2 and Dextre. It's been in use since 1994.

The Shuttle Program is in the history books now, and the PRE wouldn't have helped in the types of accidents the program suffered.

But in the future, if there's an accident that requires astronauts to travel to a rescue ship under duress, the SAFER system is preferable to being zipped up in a cloth bag like dirty laundry.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.