Imagine parallel parking a 15-passenger van into just two to three parking spaces surrounded by two-story boulders. On October 20, a University of Arizona-led NASA mission 16 years in the making will attempt the astronomical equivalent more than 200 million miles (320 million kilometres) away.

A NASA mission called OSIRIS-REx will soon attempt to touch the surface of an asteroid and collect loose rubble.

OSIRIS-REx is the United States' first asteroid sample return mission, aiming to collect and carry a pristine, unaltered sample from an asteroid back to Earth for scientific study. The spacecraft will attempt to touch the surface of the asteroid Bennu, which is hurtling through space at 63,000 miles per hour (101,000 kilometres per hour).

If all goes according to plan, the spacecraft will deploy an 11-foot-long (3-metre-long) robotic arm called TAGSAM – Touch-and-Go Sample Acquisition Mechanism – and spend about 10 seconds collecting at least two ounces (50 grams) of loose rubble from the asteroid. The spacecraft, monitored remotely by a team of scientists and engineers, will then stow away the sample and begin its return to Earth, scheduled for 2023.

You can watch this sample collection "Touch-And-Go" maneuver October 20 at 5:00 pm EDT/ 2:00 pm PDT (2100 UTC) above, or on NASA Television and the agency's website.

As senior vice president for research and innovation at UArizona and a mechanical engineer with a long career in space systems engineering, I believe this milestone for OSIRIS-REx captures perfectly the spirit of research and innovation, the careful balance of problem-solving and perseverance, of obstacle and opportunity.

OSIRIS-REx spacecraft's sampling arm. (NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

OSIRIS-REx spacecraft's sampling arm. (NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

What Bennu can teach us

In 2004, Michael Drake, then head of the UArizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory; his protégé, Dante Lauretta, then a UArizona assistant professor of planetary science; and experts from Lockheed Martin and NASA discussed the very earliest concept of the OSIRIS-REx mission and what it might achieve.

Asteroids are relics of the earliest materials that formed our solar system, and studying such a sample might allow scientists to answer fundamental questions about the origins of the solar system. Further, Bennu is a near-Earth asteroid with possible risk of impacting the Earth in the late 2100s, so the mission also is exploring ways in which such a collision might be avoided.

Perhaps, though, the most ambitious goal of the OSIRIS-REx mission is resource identification – the "RI" in OSIRIS. This means, essentially, mapping the chemical properties of Bennu to learn, among other things, about the potential for mining asteroids to produce rocket fuel – a notion which, in 2004, was far ahead of its time.

NASA selected UArizona to lead the mission in 2011, with Drake at the helm. Lauretta, a first-generation college student and UArizona alumnus, took over when Drake died that year and continues to lead OSIRIS-REx today. He would unquestionably make his predecessor proud.

While OSIRIS-REx is the first NASA mission to attempt to collect a sample from an asteroid, the scientific and technological knowledge requisite of such a mission is the result of decades of prior exploration. In the early 1990s, NASA's Galileo flew past the asteroids Gaspra and Ida. NEAR Shoemaker was the first human-made object to orbit and land on an asteroid. Before heading for the dwarf planet Ceres in 2012, NASA's Dawn spacecraft orbited and mapped extensively the asteroid Vesta.

And perhaps most significantly, in 2010, the Japanese counterpart of NASA, JAXA, returned to Earth a small amount of dust from an asteroid via its Hayabusa spacecraft.

Early last year, JAXA's Hayabusa 2 landed on and successfully collected a sample from the asteroid Ryugu. The spacecraft will return to Earth in December of this year. It has been a privilege and an absolute delight to observe and learn from the accomplishments of our colleagues in Japan.

Navigating the unexpected

OSIRIS-REx launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on 8 September 2016, and arrived at Bennu in December 2018. In the months leading up to this moment, its team of scientists and engineers has remotely conducted two rehearsals, getting very near to Bennu without touching it.

When the OSIRIS-REx team selected Bennu as its target, it suspected and hoped that the asteroid's surface would look something like a sandy beach. But the scientific process – and nature itself – is full of surprises, some challenging, all wondrous.

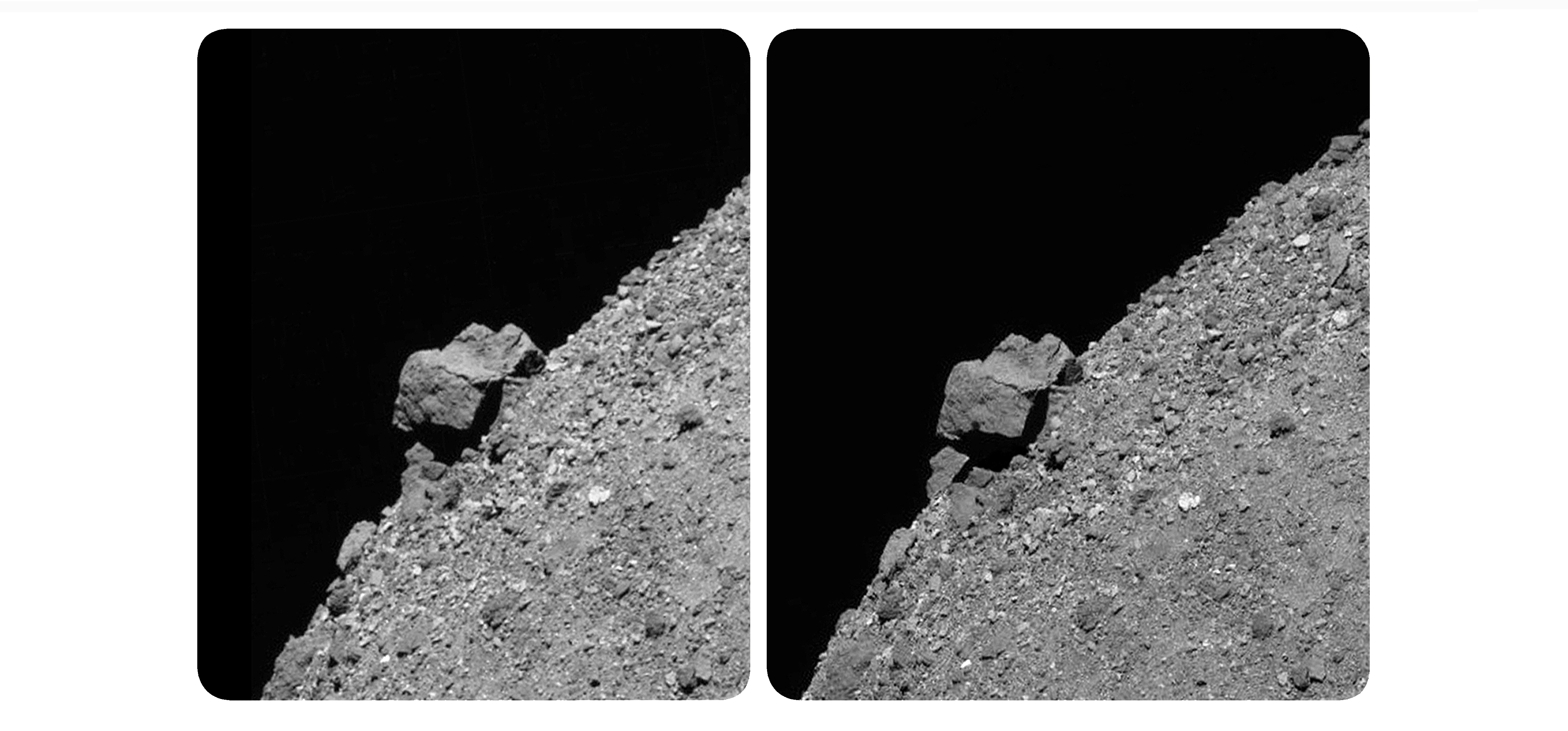

As the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft approached Bennu, its suite of high-resolution cameras beamed hundreds of photos of the asteroid back to Earth, revealing not a beachlike surface, but a rugged, boulder-strewn landscape.

This was not exactly in the plan.

The team pored over these images for months, searching for a site both wide enough for a spacecraft the size of a large passenger van to touch down and maneuver without hitting a boulder and containing material fine enough to provide loose rubble to collect.

On 12 December 2019, the OSIRIS-REx team announced the chosen landing site: Nightingale. Nightingale is home to a relatively new crater the size of a tennis court. At its edge lies a boulder the size of a two-story building.

The team, which includes hundreds of faculty, researchers and students from UArizona and several partner institutions, affectionately refers to this boulder as "Mount Doom".

In one small section of Nightingale's crater – the size of just a few parking spaces – the team identified loose rubble small enough for the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft to grab and carry away.

Bennu's 152-meter boulder jutting from its southern hemisphere. (NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

Bennu's 152-meter boulder jutting from its southern hemisphere. (NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona)

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Things could go wrong on October 20.

Aside from crashing into Mount Doom, other less dramatic, more probable risks lurk. The TAGSAM collector head could land on a rock, perched at an angle, rather than flush against a flat surface of rubble, making its collection far less effective.

Because the collector head can accommodate particles only the size of a nickel or smaller, there is also the risk of it being effectively "clogged" by something larger. In uncharted territory, things don't always go according to plan.

Nevertheless, we are optimistic.

The age-old adage rings true: Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

We already have gained so much knowledge from the OSIRIS-REx mission, and we will continue exploring and problem solving with the same bold determination that has taken us so far. ![]()

Elizabeth Cantwell, Professor of Practice for Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering and Senior Vice President for Research & Innovation, University of Arizona.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.