Today's painkillers are effective enough at doing their job, but carry the risk of side effects and negative health impacts – a problem that a new study tackles by homing in on the pain relief part in mice and lab-grown cells.

Technically, these painkillers are known as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs. They work by blocking the production of prostaglandins, chemicals released by the immune system that trigger inflammation and pain, as a way of repairing damage to the body and signaling an emergency situation.

In this study, led by pharmacologist Romina Nassini from the University of Florence in Italy, mouse models and human cells were manipulated and examined to identify the cell receptors activated by prostaglandins, and in particular, those responsible for pain signals.

Related: Musicians Don't Feel Pain Like The Rest of Us, Surprising Study Reveals

If future drugs can tackle pain without interfering with inflammation, rather than blocking both pain and inflammation at the same time, as current painkillers do, they could be more effectively targeted and come with fewer side effects.

"Inflammation can be good for you – it repairs and restores normal function," says clinical pharmacologist Pierangelo Geppetti, from the University of Florence. "Inhibiting inflammation with NSAIDs may delay healing and could delay recovery from pain."

"A better strategy to treat prostaglandin-mediated pain would be to selectively reduce the pain without affecting inflammation's protective actions."

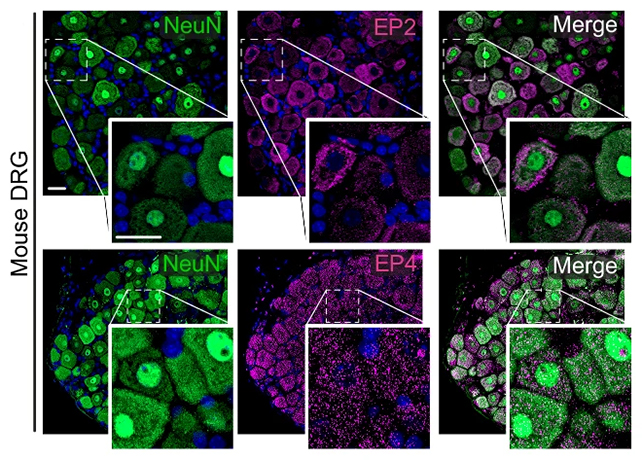

The key finding from this research was the realisation that prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which plays a major role in inflammatory pain, uses a different cell receptor than previously thought. The team was also able to identify how PGE2 functioned through pathways in Schwann cells, which act as support workers for nerves.

In further experiments, targeting the PGE2 cell receptor successfully cut out the pain signaling without obstructing inflammation, which helps mount a swift immune response by moving fluid (hello swelling) and immune cells to injured or infected sites.

"To our great surprise, blocking the EP2 receptor in Schwann cells abolished prostaglandin-mediated pain but the inflammation took its normal course," says Geppetti. "We effectively decoupled the inflammation from the pain."

It's early days for this research, which thus far only covers animal experiments and lab tests, but it gives scientists a way in to developing painkillers that are safer than today's NSAIDs – which have been linked with increased risks of damage to the heart, stomach, kidneys, and liver.

As is always the case with inflammation, caution and care are required: The response of the immune system needs to be balanced so that it does its job of repairing the body, without becoming too active or lasting too long, which brings more problems in the form of chronic, inflammatory diseases.

The next steps for this research are more pre-clinical studies before human trials can be considered. Ultimately, we may end up with new pain relief treatments for a range of problems, from sprains and strains to arthritis, which can work on their own or in combination with other drugs.

"Inflammation and pain are usually thought to go hand in hand," says molecular pathobiologist Nigel Bunnett, from New York University. "But being able to block pain and allow inflammation – which promotes healing – to proceed is an important step in improved treatment of pain."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.