A new pill for treating dementia is delivering promising "topline" results in early-stage clinical trials, according to a recent press release by its makers.

The treatment, called VES001 after its developer Vesper Bio, is designed to tackle frontotemporal dementia (FTD) – the most common type of dementia in the under-60s.

In a two-part preliminary safety trial at two medical centres in the Netherlands and the UK, VES001 was given to people showing no signs of FTD, including six volunteers with an increased genetic risk for the condition.

Related: Time Itself Could Be a Crucial Element in Preventing Dementia, Study Finds

In those at-risk participants, the daily treatment boosted blood and spinal fluid levels of a protein called progranulin – often lacking in people with FTD – by an average of more than 95 percent, relative to their baseline at the start of the 3-month trial.

With no serious side effects reported, the treatment has now cleared its first safety hurdle after years of research investigating ways to counter progranulin deficits in the brain.

"This means we now have hope for a treatment that could potentially prevent the development of this form of dementia in people at genetic risk – thereby conceptually transforming the future of dementia therapy," says Vesper Bio's Chief Scientific Officer Anders Nykjær, a medical biochemist at the Danish Research Institute of Translational Neuroscience (DANDRITE) at Aarhus University in Denmark.

The researchers running the trial haven't shared detailed data beyond the topline results outlined in the company's press release, and the findings need to be peer-reviewed. While the results are encouraging, they need to be interpreted with caution.

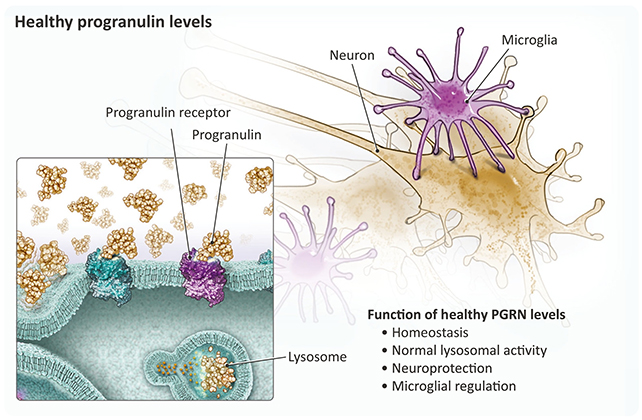

Progranulin plays a vital role in the health and functionality of neurons. Scientists have previously linked mutations in the progranulin gene (GRN) – and a subsequent disruption in progranulin production – with FTD-causing damage in the brain.

That progranulin shortfall is what VES001 has been designed to target, and the researchers behind the trial believe it could help people with and without GRN mutations. If levels of progranulin can be maintained, FTD may, in theory, never develop.

The treatment focuses on the sortilin receptor, known to clear progranulin from the brain. The primary function of VES001 is to limit the effectiveness of the sortilin receptor, slowing the removal of progranulin.

"For several years, we have been studying the role of the sortilin receptor in neurodegeneration," says Nykjær.

"Seeing this knowledge translated into a treatment that now shows promising clinical results is a major step forward for the field – and a testament to the vital importance of basic research for the development of new therapies."

In those with a GRN genetic mutation, the treatment was shown to return progranulin to near-normal levels in both blood plasma and the cerebrospinal fluid that travels around the body's nervous system, delivering nutrients and removing waste.

The researchers won't be drawn on a timeline for treatments becoming available to the public – additional clinical trials will be required before that happens – but it's a case of so far, so good for VES001. And the difference it could make is huge.

"The increase of progranulin levels back to normal levels in these asymptomatic mutation carriers – who know they will develop symptoms in the next 10 to 20 years – speaks to the future potential of this treatment to prevent people ever developing symptoms of FTD," says neurologist Jonathan Rohrer, principal investigator of the trial at from the Queen Square Institute of Neurology at University College London.

The trials are registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, here and here, and the Vesper Bio press release is here.