A new anti- cancer hydrogel patch appears to hit tumours with a highly targeted, three-pronged volley of drugs, researchers have found.

The patch has so far only been tested on mice, but promising results have been reported both before and after tumour removal, and the team behind the tiny devices says they could have a major impact in the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Right now, the most important step in the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer is to try and surgically remove as much of the tumour as possible, but completely clearing out the cancerous cells can be very difficult. That's where this new hydrogel patch comes in.

The patch has been designed to specifically target parts of the tumour left behind - something that could replace the debilitating, and not necessarily effective, a blast of chemotherapy that's currently used.

"[We wanted] to think a little bit differently, to look at how we can leverage advancements in materials science, and in particular nanotechnology, to treat the primary tumour in a local and sustained manner," explained team leader Natalie Artz, from MIT's Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES).

The patch worked so well during animal testing, it started clearing up tumours even before they'd been surgically removed. In cases where the tumours had already been extracted, no relapses were recorded - a big improvement over the 40 percent of cases where the patch was not applied and the disease returned.

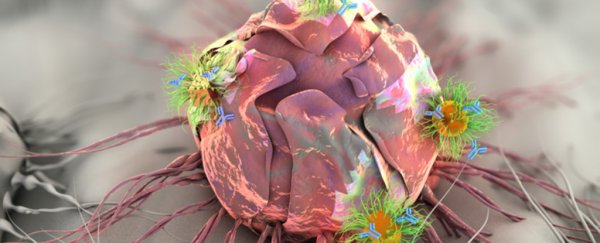

The patches work in a three-step process, which starts with the release of tiny gold nanorods designed to thermally destroy the tumour. The second volley of attack is provided by chemo drugs loaded inside the nanorods, which are released as more heat is applied.

Finally, gold nanospheres (not affected by heat) are used to deliver RNA-based gene therapy to the site of the tumour, silencing a particular gene known to cause healthy cells to mutate into tumour cells in colorectal cancer patients.

RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is a close biological cousin of DNA, and scientists have recently discovered ways to reprogram RNA to change the way cells evolve inside the body. In this case, that change effectively stops them from becoming cancerous.

The researchers say the patch could be applied both before the tumour is removed, to shrink it down, or after an operation, to reduce the risk of it returning. The patches will degrade over time as they're warmed by a patient's body heat.

Colorectal cancer, otherwise known as bowel cancer, is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the US, and the third most common cancer overall. More than 1 million new cases are diagnosed every year around the world.

The next step for the team at MIT is to test their new sticky patch on larger animals in the lab, and if the results continue to be positive, human trials could be on the cards.

The research has been published in Nature Materials.