Scientists have found new evidence that brains affected by schizophrenia might be able to reorganise themselves and fight back against the disease. It's a promising new avenue for our understanding of schizophrenia, and could one day point towards a cure for an illness that's estimated to affect more than 21 million people worldwide.

The new study found that, when it comes to grey matter volume, this repairing effect over time actually makes the brains of schizophrenic patients grow to be more like the brains of people without the disease – which could help us to come up with new ways to develop treatments for the condition.

The study analysed 98 people with schizophrenia, and 83 people without. They found a small increase in tissue in certain parts of the brain in the schizophrenia group after MRI scans were taken. Those small increases were noted alongside reduced amounts of grey matter in other areas.

That goes against the established and generally accepted view of schizophrenia as a disease that permanently damages brain tissue in its initial stages, which cannot be reversed.

While it's only a small study with a relatively tiny sample of patients examined, if the findings can be replicated and built upon, it could signal a serious shift in the way scientists and doctors think about the illness.

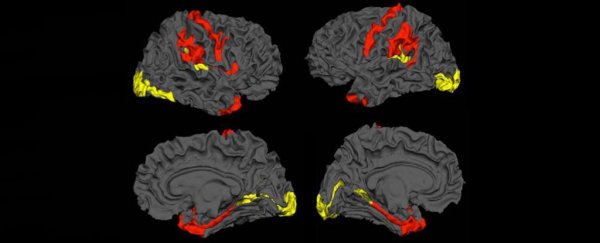

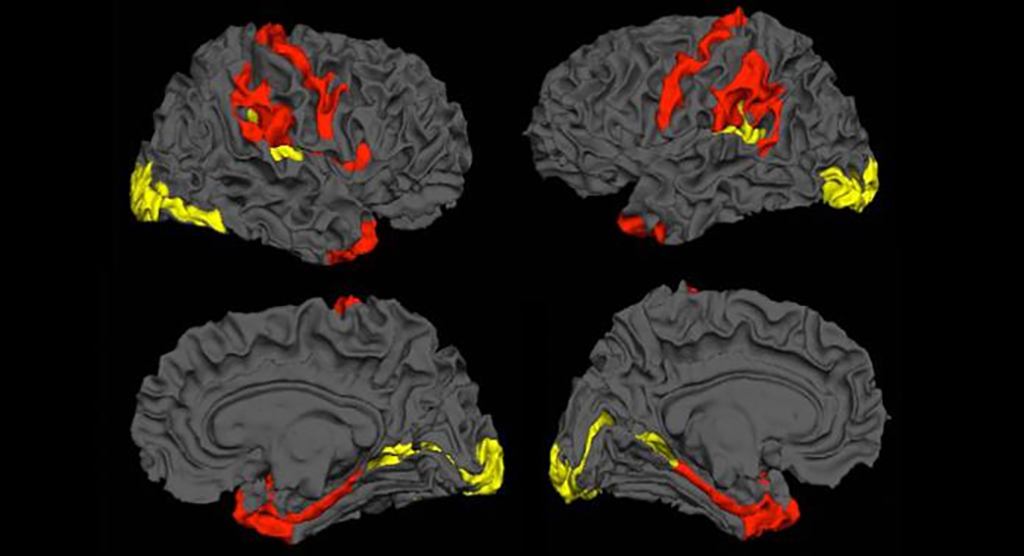

Dynamic cerebral reorganisation. Credit: Lena Palaniyappan

Dynamic cerebral reorganisation. Credit: Lena Palaniyappan

"Our results highlight that despite the severity of tissue damage, the brain of a patient with schizophrenia is constantly attempting to reorganise itself, possibly to rescue itself or limit the damage," said one of the team, Lena Palaniyappan from the Lawson Health Research Institute in Canada.

Palaniyappan and his colleagues used a technique called covariance analysis to study schizophrenic brains more comprehensively than they have been in the past, finding that damaged brains deviate from the norm most significantly early on in the progress of the disease.

"The findings suggest that in terms of grey matter volume, the brains of schizophrenic patients become more 'normal' the longer that they have the condition," Rhodi Lee reports for Tech Times.

They also found that the amount of deviation doesn't necessarily match up with how severe the schizophrenia becomes further down the line.

Both those clues – and the increases in brain tissue that have been spotted – hint at an attempt at self-healing, and possibly one that could be enhanced with the right medical treatments.

Such potential treatments could "harness the brain's own compensatory changes in the face of this illness", according to Paul Links of the London Health Sciences Centre in Canada, who wasn't involved in the study.

We still don't know what causes schizophrenia, and most medicines and therapies are designed to reduce the effects and allow those who experience it to live a more normal life. If the latest research can be developed, it could offer invaluable insight into how the disease takes hold, as well as new ways we can fight it.

The findings have been published in Psychology Medicine.