Researchers have predicted that antimicrobial resistance will kill 300 million people and cost the global economy US$100 trillion by 2050 if government action is not taken to ease our reliance of antibiotic medications.

The newly released Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, chaired by renowned economist, Jim O'Neill, predicts that our global GDP would dip by 0.5 percent by 2020 and will end up 1.4 percent smaller by 2030, purely due to the steady march of resistant bacteria.

"One of the things that has been lacking is putting some pound signs in front of this problem," Michael Head, an expert in infection and population health at University College London in the UK told Anthony King at Chemistry World, who compares the situation to how action was finally taken to deal with HIV. "The world was slow to respond [to HIV], but when the costs were calculated the world leapt into action."

According to Head, considering how much antimicrobial resistance is set to cost us over the next 50 years, right now, we're spending a meagre amount of available research funds on fixing the problem. He says in Europe and the UK, less than 1 percent of research funds were spent on the field between 2008 and 2013. Of the £2.6 billion worth of funds allocated to infectious diseases research in the UK, he said, just £102 million is being used to fight antimicrobial resistance.

And these numbers aren't carefully exaggerated scare tactics - health systems economist from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Richard Smith, says that the report's figures are more likely to be underestimated. "It takes into account effects on labour productivity and labour workforce issues, but we don't know what the public reaction will be. From previous pandemics and outbreaks we know behavioural effects can be much worse on an economy than the impact of the disease," he says.

The report also mentions at the end that their figures are likely underestimated due to a lack of data.

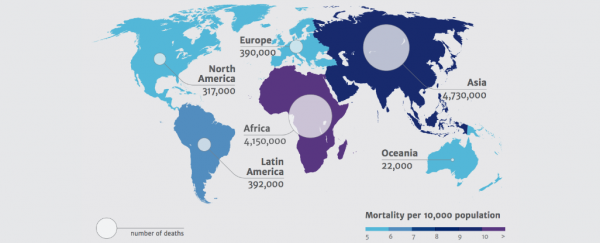

According to Haroon Siddique at The Guardian, the report says the most populous countries - India and China - will have to deal with 2 million and 1 million deaths respectively every year by 2050 if nothing is done, and one in every four deaths in Nigeria will be due to antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Right now, a "low estimate" of the annual number of antimicrobial residence diseases is 700,000.

King reports that Australian management consultancy firm KPMG modelled the future impact of antimicrobial resistance related to Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. Their hypothetical scenario asked what would happen if resistance rose by 40 percent, and found that the number of infections around the world would double. They identified malaria resistance as having the potential to kill the most people, while E. coli infections would cost the most to treat, being capable of such widespread infections.

"You can look at antibiotic resistance as a slow moving global train wreck, which will happen over the next 35 years," health law expert Kevin Outterson from Boston University in US told Chemistry World. "If we do nothing, this report shows us the likely magnitude of the costs."

Outterson says the entire pharmaceutical marketplace needs to be overhauled in order to deal with the problem. He says we need to encourage pharmaceutical companies who are developing new antibiotic medications to sell them modestly for at least the first 10 years of their release on the market, and reserve it for the only the sickest patients. Of course, pharmaceutical companies aren't going to be interested in cutting back on how much product they can sell, so Outterson suggests that governments and health organisations help pay back their R&D costs by paying for access to these drugs.

Another option, says King at Chemistry World, is instead of waiting decades for a new drug to be developed, tested, and put on the market, we could be putting old drugs back into commission. The EU is now funding clinical trials on five drugs that were developed more than 30 years ago to see if they can get them back on the market.

"When we understand a threat, governments respond with energy and with money," Outterson told Chemistry World. "The threat posed by bacterial resistance is even greater than that of Ebola. If this report accurately predicts the world we live in in 2050, then we will have failed on a monumental scale to preserve a global public good."

It's not all doom and gloom though, researchers around the world are making progress on antibiotic alternatives, such as this team in Switzerland, which is using cell structures called liposomes to bait, trap and neutralise deadly bacterial toxins.

Sources: Chemistry World, The Guardian