The glorious geological features of Yellowstone National Park in the US, powered by wells of hot water, are well known to the millions of visitors it attracts each year. What we know less about is the underlying 'plumbing' below the site.

A new study reveals some of that hidden detail for the first time, charting the paths of the hot hydrothermal fluids that make their way to the surface (with great speed at times), and the geological faults and fractures that determine their routes.

The data was gathered via an instrument called a SkyTEM312, carried by a helicopter, which sends bursts of electromagnetic signals downwards, resulting in different responses depending on the features of the rock underneath the surface.

(W. Steven Holbrook)

(W. Steven Holbrook)

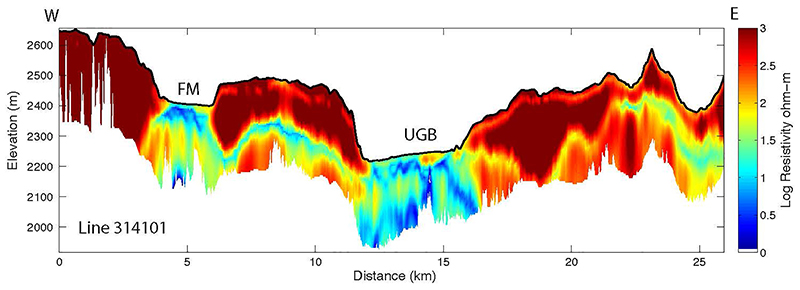

Above: A subsurface image produced from SkyTEM data, with electrically conductive hydrothermal pathways in blue and electrically resistive lava flows in red.

"Our knowledge of Yellowstone has long had a subsurface gap," says geophysicist Steven Holbrook, from Virginia Tech. "It's like a 'mystery sandwich'.

"We know a lot about the surface features from direct observation and a fair amount about the magmatic and tectonic system several kilometers down from geophysical work, but we don't really know what's in the middle. This project has enabled us to fill in those gaps for the first time."

The data gathered by SkyTEM were carefully analyzed to reconstruct a cross-section of the depths below Yellowstone. The team worked out that a lot of the park's most famous features lie on top of clay-capped, high-flux channels running along volcanic rock faults and fractures – they're shown up by their low electrical resistivity.

Shallow groundwater flows along these channels, the analysis revealed, mixing with heated water rising from depths of more than a kilometer (0.6 miles) under the park. Variations in this mix lead to decompression boiling, degassing, and conductive cooling, causing the thermal phenomenon that Yellowstone is known for.

One of the surprises in the study was the similarity in the deeper structure beneath parts of the park, with very different chemistry and temperatures on the surface. It seems those differences are caused by the varying ways that groundwater and heated water mixes, rather than other geological factors.

"The combination of high electrical conductivity and low magnetization is like a fingerprint of hydrothermal activity that shows up very clearly in the data," says Holbrook. "The method is essentially a hydrothermal pathway detector."

The helicopter and its attached SkyTEM weren't able to cover the whole of the almost 9,000 square kilometer (3,475 square mile) park, and the scanning resolution wasn't high enough to identify individual water channels leading to specific features, but the data is still very useful to scientists in a range of different fields.

Biologists, geologists and hydrologists have already expressed an interest in using the data, the authors of the new study say, looking at everything from microbiological diversity across the park to the historical record of past lava flows.

The work reported in this study could even be used to get advanced warnings of volcanic hazards, which occur when the clay layers underneath Yellowstone get temporarily sealed off, leading to a dangerous and potentially explosive build up of gas.

"The data set is so big that we've only scratched the surface with this first paper," says Holbrook. "I look forward to continuing to work on this data and to seeing what others come up with, too. It's going to be a data set that keeps on giving."

The research has been published in Nature.