Research suggests young, active people are increasingly being diagnosed with osteoarthritis at much earlier ages than many expect. I have seen its effects first-hand among my own friends.

One, a keen marathon runner, developed stage 2 osteoarthritis in her mid-30s. Several well-known public figures, including Robbie Williams, Tiger Woods, and Andy Murray, have also spoken openly about experiencing the condition relatively young.

Osteoarthritis is often dismissed as an inevitable consequence of ageing, but it can erode quality of life at any age. It can turn everyday activities such as walking, climbing stairs, or exercising into painful challenges.

More than 600 million people worldwide live with osteoarthritis, and its risk factors are varied. They include obesity, ageing, metabolic disorders, chronic inflammation, previous joint injury, and repetitive mechanical stress.

For younger people, osteoarthritis can be particularly devastating. Pain and stiffness can limit physical activity during years when work, caregiving, and family life are often most demanding.

It can affect mental health, restrict career choices, and reduce the ability to stay active, which in turn increases the risk of other long-term health conditions. Unlike older adults, younger patients may also face decades of managing symptoms and repeated treatments.

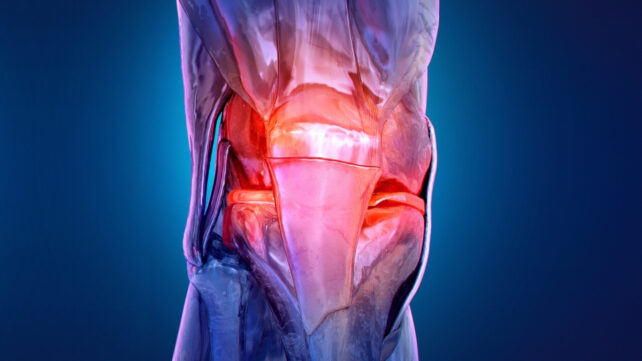

Osteoarthritis develops when the smooth cartilage that cushions joints gradually breaks down. Cartilage normally acts as a shock absorber, allowing bones to move smoothly over one another.

As it wears away, joints lose this protection. Bone surfaces begin to rub together, leading to pain, stiffness, and the grinding or crunching noises many people jokingly refer to until the discomfort becomes impossible to ignore.

The condition does not appear overnight. Osteoarthritis usually takes years, and often decades, to develop. Early symptoms are often subtle and easy to dismiss: mild knee pain after activity, stiffness that eases with movement, or discomfort that comes and goes. Many people delay seeking medical advice until pain becomes persistent and joint damage is already advanced.

At present, treatment focuses on managing symptoms rather than reversing the disease. This includes exercise therapy, pain relief, and therapeutic injections.

These injections may include platelet-rich plasma, which is made from a concentrated portion of a patient's own blood and contains growth factors thought to support tissue repair. Others use platelet-derived vesicles, tiny particles released by platelets that carry biological signals involved in inflammation and healing.

However, most evidence for vesicle-based approaches currently comes from animal studies, including rat models, and they are not yet used routinely in human clinical practice. Hyaluronic acid may also be injected. This is a gel-like substance naturally found in joint fluid that helps lubricate and cushion the joint.

These treatments aim to reduce pain or improve joint movement rather than repair damaged cartilage. For some people, they provide temporary relief. Ultimately, however, when joint damage becomes severe, total joint replacement may be the only remaining option.

But what if osteoarthritis could be detected much earlier, before pain and irreversible damage set in?

Early prevention and early intervention have the potential to reduce pain, preserve mobility, and significantly lower healthcare costs. The challenge has always been identifying osteoarthritis early enough to act.

Early diagnosis

This is where emerging diagnostic technologies may eventually offer a breakthrough. Every chemical compound in the body has a unique molecular structure, and when analysed, it produces a distinctive pattern known as a "spectral fingerprint".

This fingerprint reflects the chemical composition of a sample, such as blood serum. In people with osteoarthritis, researchers have observed subtle changes in inflammation, metabolism, and tissue turnover that may alter this chemical profile.

One way of studying these fingerprints is through a technique called attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Despite the intimidating name, the principle is straightforward.

A small blood sample is exposed to infrared light, and the way that light is absorbed provides information about the types of molecules present. Changes in proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules can leave measurable signatures, which researchers are investigating as potential indicators of osteoarthritis.

These approaches are still largely used in research settings and are not yet part of routine clinical care. Even at this early stage, this research is important because it may eventually allow osteoarthritis risk to be identified earlier, when lifestyle changes and targeted interventions are more likely to protect joint health.

By combining this approach with computational analysis, researchers can identify complex chemical patterns associated with disease. In practice, this means comparing blood samples from people with and without osteoarthritis and detecting differences that are invisible to the naked eye.

Similar approaches can also be used with other laboratory techniques, including spectroscopy-based methods and molecular biology tools, to identify biomarkers linked to early joint disease.

Related: Signs of Rheumatoid Arthritis Uncovered Years Before Symptoms Appear

This kind of early detection could transform how osteoarthritis is managed. Identifying risk before symptoms become severe would allow people to take action earlier, through targeted exercise, weight management, injury prevention, and tailored treatment strategies.

Osteoarthritis does not have to mean decades of pain and limitation. By shifting the focus from late-stage treatment to early detection and prevention, it may be possible to change the trajectory of the disease and improve quality of life for millions of people worldwide.![]()

Atiqah Aziz, Senior Research Officer at the Tissue Engineering Unit (TEG), National Orthopaedic Centre of Excellence for Research & Learning (NOCERAL), Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.